Who are the “Wrong Hands” in Yemen?

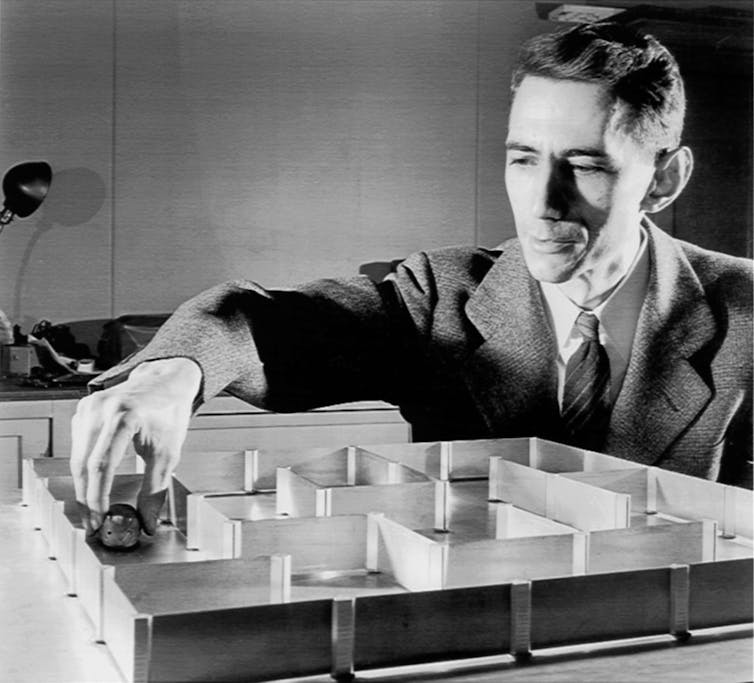

Drawing by Nathaniel St. Clair

Politics makes strange bedfellows. Some of them want to kill us.

Take Abu Abbas (as Henny Youngman used to say: “Please.”). Abu Abbas (a nom de guerre for one Adil Abduh Fari al-Dabhani) is the founder and leader of the Abu Abbas brigade, a militia fighting on the government side in Yemen.

Abbas and his eponymous militia are unintended beneficiaries of Pentagon largesse. According to CNN, the Abu Abbas brigade possesses armored tactical military vehicles manufactured by US company Oshkosh Defense. We know this because the Abu Abbas brigade openly paraded the American-made vehicles through the streets of the Yemeni city of Taiz in 2015. Apparently, President Donald Trump isn’t the only one who loves a military parade.

There are two things you should know about Abu Abbas. First, the Abu Abbas brigade isn’t supposed to have the vehicles. The US sold the vehicles to the UAE which violated the sales agreement by transferring them to a third party, the Abu Abbas brigade, without the authorization of the US.

Second, Abu Abbas is affiliated with Al-Qaeda. The Trump Administration placed sanctions on Abu Abbas in 2017, calling him a fundraiser for Al-Qaeda who, in addition, “served with” ISIS. The Washington Post calls Abbas “a powerful Yemeni warlord.”

To recap, the UAE, a nominal US ally, illegally transferred military hardware to a militia affiliated with a major US enemy. Al-Qaeda, you’ll recall, kills Americans. And still does. Ahmed Mohammed Alshamrani, the Saudi pilot trainee who murdered three US sailors at a US naval base in Florida in December 2019, was in contact with Al-Qaeda’s Yemeni franchise, Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). The FBI learned this from examining Alshamrani’s phone records. AQAP has taken credit for the Florida attack.

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the UAE, which have been making war on Yemen since 2015, routinely transfer US arms to extremist militias involved in the fighting. To its shame, the US has been supporting the Saudi-led coalition with arms sales, intelligence sharing, and targeting assistance since 2015. Nobel Peace Prize (Sorry, Mr. Trump. I mean Noble Peace Prize) laureate Barack Obama took the US into the war in 2015. The war in Yemen is now the world’s worst humanitarian disaster in which at least 100,000 people have died.

CNN told the Department of Defense that US weapons were winding up in the hands of extremist militias. DoD said the matter was already being looked into. Great news! The DoD has cleared the UAE of wrongdoing, according to sources in the executive branch and on both sides of the aisle in Congress. So I guess we have nothing to worry about.

Either that, or the US doesn’t care that American weapons are winding up in the hands of US enemies just so long as the US gets to sell more and more arms. The Trump Administration doesn’t care how. If selling arms requires circumventing Congress, Trump is cool with that. So is Trump’s secretary of state, Mike Pompeo.

In May 2019, Secretary Pompeo concocted a phony emergency with Iran in order to push through $8 billion in arms sales without having to consult Congress. State Department Inspector General Steve Linick was investigating the legality of the sale when President Trump fired him at Secretary Pompeo’s behest on May 15 of this year.

CNN learned from four sources that Pompeo had apparently already decided to push the sale through when he asked subordinates to dream up reasons to justify the sale’s legality. According to Politico, “high-level officials of the State Department, Pentagon and within the intelligence community” advised Pompeo against invoking an emergency in order to make the arms sale.[1]

Going further back, on September 12, 2018, Secretary Pompeo falsely certified that the Saudis and the UAE were “undertaking demonstrable actions to reduce the risk of harm to civilians and civilian infrastructure” in Yemen. Hogwash. The month before, the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights reported that “There is little evidence of any attempt by parties to the conflict to minimize civilian casualties.” Had Pompeo told the truth, the US would have been required under the National Defense Authorization Act for 2019 to terminate military assistance to the Saudis and the UAE. That would have jeopardized arms sales.

Even if US arms were not being transferred to extremist militias, arming the Saudis and UAE is bad enough. The Saudi-led coalition uses US arms in indiscriminate attacks on civilians, in contravention of international law. Fragments of a bomb manufactured by US defense contractor Lockheed Martin were found at the scene of a 2019 bombing which killed 40 Yemeni children aboard a school bus. CNN and other media outlets engage in much hand-wringing about US weapons winding up in the “wrong hands,” by which they mean militias. Why aren’t the Saudis and UAE considered the “wrong hands,” too? Oh, I know. Because they buy US arms.

Notes.

1) On June 24, 2019, Senator Robert Menendez (D-NJ) introduced a bill, the Saudi Arabia False Emergencies (“SAFE”) Act. The bill restricts the president’s ability to invoke an emergency in order to evade Congressional review of arms sales to a handful of countries: members of NATO, Australia, Japan, South Korea, New Zealand, and Israel. The list conspicuously omits Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. ↑