Ahad Ha’Am’s Prophetic Warning about Political Zionism

by Sheldon Richman

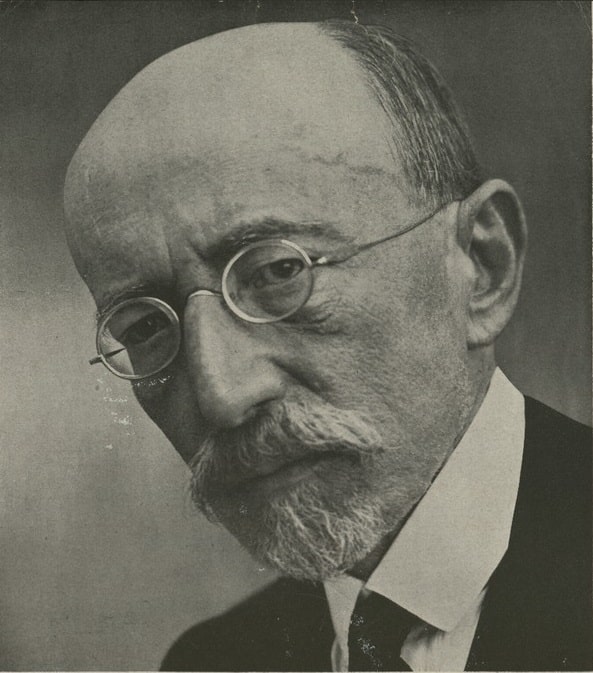

Ukrainian-born Asher Zvi Hirsch Ginsberg (1856-1927), whose pen name was Ahad Ha’Am (Hebrew for one of the people), was a proponent of Spiritual, or Cultural, Zionism, which made him a rival to Theodor Herzl and Political Zionism, the movement dedicated to creating a nation-state in Palestine for all Jewish people worldwide. Ahad Ha’Am remains relevant to understanding the roots of the conflict in Palestine and Israel that has cost so many innocent lives. Hans Kohn, a Bohemian-born American writer, shed light on Ahad Ha’Am’s thinking about the “Arab problem” for Herzl’s movement in “Zion and the Jewish National Idea,” published in Menorah Journal, Autumn-Winter 1958. (The journal ceased publication in 1962.) Here’s part of what Kohn wrote. Pay close attention to the quotes from Ahad Ha’Am:

In 1891 Ahad Ha-‘Am laid his finger on the problem which, for practical and ethical reasons alike, was the fundamental though neglected problem of Zionism in Palestine — the Arab problem. To the eyes of most Zionists, the land of their forefathers appeared empty, waiting for the return of the dispersed descendants as if history had stood still for two thousand years. From 1891 on Ahad Ha-‘Am stressed that Palestine was not only a small land but not an empty one… He pointed out that there was little untilled soil in Palestine, except for stony hills and sand dunes. He warned that the Jewish settlers must under no circumstances arouse the wrath of the natives by ugly actions; must meet them rather in the friendly spirit of respect. “Yet what do our brethren do in Palestine? Just the very opposite! Serfs they were in the lands of the Diaspora and suddenly they find themselves in freedom, and this change has awakened in them an inclination to despotism. They treat the Arabs with hostility and cruelty, and even boast of these deeds; and nobody among us opposes this despicable and dangerous inclination.” That was written in 1891 when the Zionist settlers formed a tiny minority in Palestine. “We think,” Ahad Ha-‘Am warned, “that the Arabs are all savages who live like animals and do not understand what is happening around. This is, however, a great error.”

This error unfortunately has persisted ever since. Ahad Ha-‘Am did not cease to warn against it, not only for the sake of the Arabs but for the sake of Judaism and Zion. He remained faithful to his ethical standards to the end. Twenty years later, on July 9, 1911, he wrote to a friend in Jaffa: “As to the war against the Jews in Palestine, I am a spectator from afar with an aching heart, particularly because of the want of insight and understanding shown on our side to an extreme degree. As a matter of fact, it was evident twenty years ago that the day would come when Arabs would stand up against us.” He complained bitterly that the Zionists were unwilling to understand the people of the land to which they came and had learned neither its language or its spirit….

In a letter of November 18, 1913 to Moshe Smilansky, a pioneer settler in Palestine, Ahad Ha-‘Am had protested against another form of nationalist boycott proclaimed by the Zionist labor movement in Palestine against the employment of Arab labor, a racial boycott: “Apart from the political danger, I can’t put up with the idea that our brethren are morally capable of behaving in such a way to men of another people; and unwittingly the thought comes to my mind: If it is so now, what will be our relation to the others if in truth we shall achieve ‘at the end of time’ power in Eretz Israel? If this be the ‘Messiah,’ I do not wish to see him coming.”

Ahad Ha-‘Am was in the prophetic tradition not only because he subjected the doings of his own people to ethical standards. He also foresaw, when very few realized it, the ethical dangers threatening Zion.

Ahad Ha-‘Am returned to the Arab problem in another letter to Smilansky, written in February, 1914. Smilansky had been bitterly attacked by Palestinian Zionists because he had drawn attention to the Arab problem. Ahad Ha-‘Am tried to comfort him by pointing out that the Zionists had not yet awakened to reality. “Therefore they wax angry toward those who remind them that there is still another people in Eretz Israel that has been living there and does not intend at all to leave its place. In the future, when this illusion will have been torn from their hearts and they will look with open eyes upon the reality as it is, they will certainly understand how important this question is and how great is our duty to work for its solution.”

…In 1920 (three years before the Balfour Declaration) Ahad Ha-‘Am warned against exaggerated Zionist hopes. “The Arab people,” he wrote, “regarded by us as nonexistent ever since the beginning of the colonization of Palestine, heard [of the Zionist expectations and plans] and believed that the Jews were coming to drive them from their soil and deal with them at their own will.” Such an attitude on the part of his own people seemed to Ahad Ha-‘Am unthinkable. In his interpretation of the Balfour Declaration he stressed that the historical right of the Jews in Palestine “does not affect the right of the other inhabitants who are entitled to invoke the right of actual dwelling and their work in the country for many generations. For them, too, the country is a national home, and they have a right to develop national forces to the extent of their ability. This situation makes Palestine the common land of several peoples, each of whom wishes to build its national home there. In such circumstances it is no longer possible that the national home of one of them could be total…. If you build your house in an empty space but in a place where there are also other homes and inhabitants, you are an unrestricted master only inside your own house. Outside the door all the inhabitants are partners, and the management of the whole has to be directed in agreement with the interests of them all.”

How different things would have been if the Political Zionists had paid heed to Ahad Ha’am.

Sheldon Richman is the executive editor of The Libertarian Institute and a contributing editor at Antiwar.com. He is the former senior editor at the Cato Institute and Institute for Humane Studies; former editor of The Freeman, published by the Foundation for Economic Education; and former vice president at the Future of Freedom Foundation. His latest books are Coming to Palestine and What Social Animals Owe to Each Other.

https://www.antiwar.com/blog/2023/12/17/ahad-haams-prophetic-warning-about-political-zionism/

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home