The price of ‘victory’: How Israel created one of its own worst enemies

The Jewish state triumphed in the 1982 Lebanon War, but years later the victory appears pyrrhic

The battle for Gaza adds yet another page to Israel’s long list of military operations in Arab nations and enclaves. We are shocked by the brutal fighting going on today, but history has seen many similar military operations where it was impossible to draw the line between war and terrorism. The 1982 Lebanon War is one such example. Israel may have won that war, but as a result it only acquired a fiercer enemy.

Setup for slaughter

By the mid-1970s, Israel had defeated the regular armies of several opposing Arab nations. However, the Jewish state still had an irreconcilable enemy: the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) headed by Yasser Arafat. The PLO was initially based in Jordan, but when it came into conflict with the local authorities, it was forced to move to Lebanon.

At the time, Lebanon – a small picturesque Arab country to the north of Israel – was torn by internal contradictions. The country had a large Arab-Christian community, which had its own militia, and was also home to Muslims of both major branches of Islam (the Shiites and Sunnis), and the Druze. The Palestinians – who were numerous and willing to fight – did not contribute much peace to the local political landscape. In 1975, a civil war broke out in Lebanon pitting the government and Christian armed groups against the Palestinians and Muslim militant groups. The front line went straight through city streets and the fighting became mixed with acts of terrorism. No one observed the ceasefire agreement.

In parallel, the PLO continued to carry out terrorist attacks in Israel. Eventually, Syria got drawn into the Lebanese conflict. Although the Syrians were initially on the opposite side and were against Arafat and his Palestinian group, Tel Aviv considered this a war between “the plague and the cholera” – in other words, two equally evil forces. When the Christians favored relations with Israel over Damascus, Syria joined the Muslim camp and practically took control over Lebanon.

At that point, Israel decided to solve the issue for good. Its main goal was to defeat PLO forces in Lebanon. One of the outspoken leaders of the 'war party' was Israeli Defense Minister Ariel Sharon. After yet another terrorist attack as a result of which an Israeli diplomat was wounded, Sharon presented a plan codenamed Peace for Galilee. Initially, it was supposed to be a small military operation, with Israeli forces not moving deep into Lebanon. Coincidentally, the terrorists who attacked the diplomat weren’t even affiliated with the PLO, but by then Israel was not to be stopped. Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin approved a broader military operation, and encouraged Sharon with the historic phrase: “Arik, I implore you, [push it] to the maximum [extent], to the maximum!”

Israel assembled impressive military forces for the operation. The border with Lebanon is about 40km long, and along this front line Israel assembled about 100,000 fighters, 1,200 tanks, 1,500 armored personnel carriers and over 600 aircraft. In addition, the Israelis were backed by Christian militants in Lebanon. Syria could muster only about 30,000 people with 350 tanks and 300 armored personnel carriers. Another 15,000 fighters were provided by the PLO, but this was not even close to a regular army. The Syrians placed their hopes in the powerful air defense system deployed in the Beqaa Valley in eastern Lebanon. The USSR-supplied anti-aircraft systems were operated by Syrian crews.

However, using the equipment proved problematic. The Syrians weren’t trained well enough, they neglected to use camouflage, didn’t establish reserve positions, and didn’t even heed the elementary requirements for operating the equipment.

Swift operation

On June 6, 1982, Operation Peace for Galilee was launched. The Israelis advanced very confidently at first, and the Palestinians retreated without fighting. In the course of just one day, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) accomplished the entire initial goal of the operation and advanced 25 miles into Lebanon.

Sharon decided to build on the initial success and launched an offensive in the direction of Beirut. At this stage, the Israelis encountered resistance by Syrian troops. Menachem Begin sent an ultimatum to Syrian leader Hafez al-Assad demanding that Syrian troops withdraw to the line that they had occupied before the start of the Israeli offensive. However, one of the demands of the ultimatum was simply impossible to carry out: Assad was required to withdraw PLO forces, but the latter did not obey him. Moreover, the Syrians were confident in their abilities.

For Lebanon, this was an awful situation. The Lebanese groups were merely minor allies of the major external forces: the PLO, Israel, and Syria. The country became a battlefield for foreign countries and armies.

On June 9, the Israeli Air Force crushed the Syrian air defense systems with a swift and powerful blow. The Israelis developed a complex attack scheme, conducted reconnaissance missions, and prepared an offensive utilizing all possible measures. As a result, they were able to initially blind and suppress, and then nearly completely destroy, Syrian air defenses.

However, it was the fighting on the ground that decided the outcome of the war.

The Syrians had fewer ground forces than the Israelis, so they limited themselves to semi-partisan actions meant to restrain their adversary and relied on city infrastructure. The offensive routes were mined and ambushes were placed on the roads. Having greater forces and better training, Israeli troops were able to defeat the Syrians in several local battles, and also formed a small cauldron (from which the Syrians managed to partly break through). But in general, the resistance on the ground turned out to be much more effective than in the air. On the night of June 11, near the village of Sultan Yaaqoub, an Israeli tank battalion confronted a Syrian tank unit, and the Israeli side emerged from the battle sustaining considerable losses. One of the M48 tanks captured by the Syrians was handed over to the USSR and ended up in the Kubinka Tank Museum.

These battles did not continue, however, and with the help of the United States, Israel and Syria concluded a ceasefire agreement.

Blood on the streets

The situation was strange, unstable, and unfavorable for all sides. The Syrians had suffered a severe blow on the battlefield, and the truce saved them from major defeat. However, for Israel, the situation was quite absurd. The formal goals of the operation were achieved, and in military terms the IDF achieved a brilliant success. The only remaining question was: so what?

The PLO was not crushed and retained most of its combat potential. The problem of Beirut loomed ahead. The civil war in Lebanon was not resolved either. The negotiations were slow and did not go particularly well. Israel demanded the withdrawal of Syrian forces from Lebanon. Neither the US nor the USSR wanted the hostilities to continue, but they preferred to admonish the parties rather than actively support them.

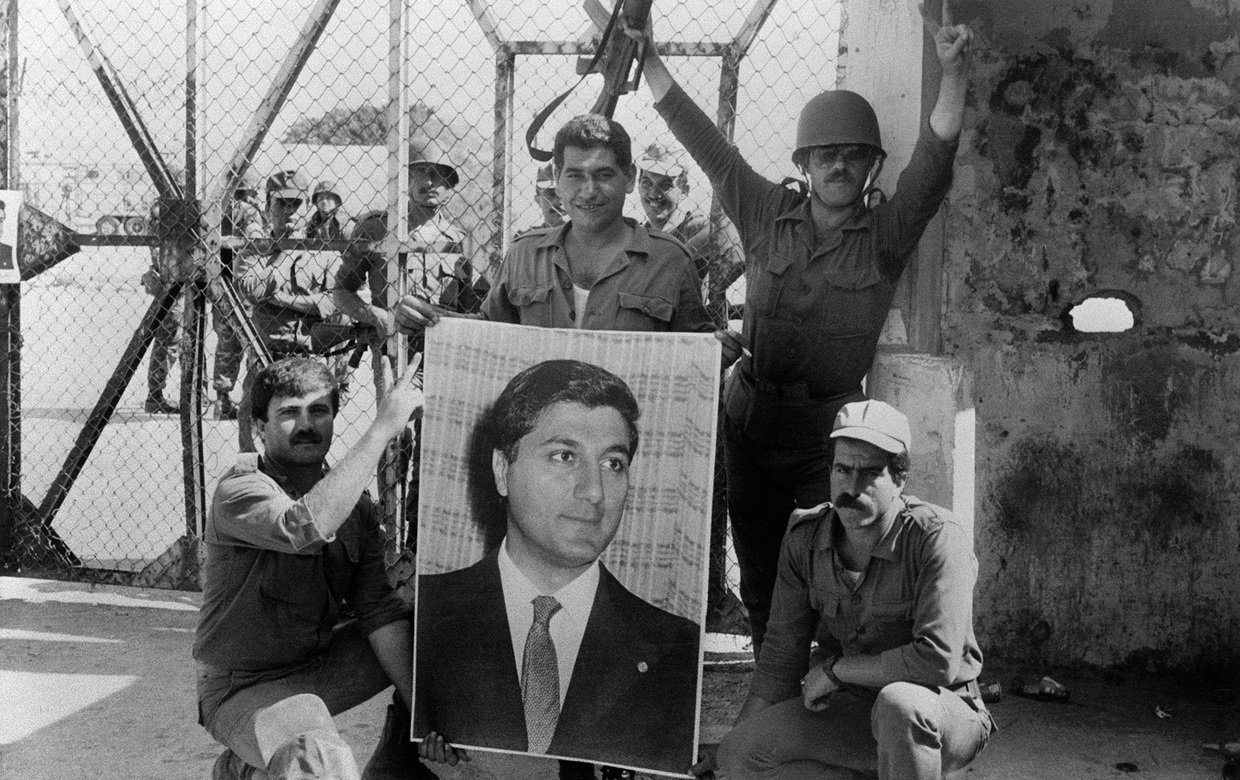

In the second half of June, IDF units started shelling Beirut. The city was in flames. The USSR sent a group of military advisers and loads of weapons to Lebanon. Meanwhile, the Israelis were gradually destroying Beirut. At the end of July, water and electricity supplies to the city were cut off. In August, Beirut was stormed. Palestinian militants resisted as long as possible, but military luck was on the side of the much more numerous, better armed and trained Israeli army, which worked its way through the burning streets. As a result, over 14,000 Palestinian militants and Syrian soldiers retreated from Beirut, mainly to Syria. Arafat also fled. Bachir Gemayel – a young and energetic politician and one of the leaders of the Christian party– was elected president of Lebanon. It seemed that Tel Aviv could now fully celebrate its victory…

...but just three weeks later, on September 14, Gemayel was killed by a powerful explosive device, right at the headquarters of the Christian Phalangist party. The bombers were from a small pro-Syrian Arab group. Twenty-seven people died as a result of the terrorist attack, including the president of Lebanon. But the worst was yet to come.

Since the 1940s, there were Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon. Eventually, from wind-blown tents these camps had grown into real cities. However, they were basically ghettos, and the Palestinians living there had almost no rights. Extremist views and criminal behavior thrived in these communities. In Beirut, Palestinians lived in the western districts of the city, which the IDF did not enter.

Most likely, some PLO militants remained in the refugee camps. However, it was almost impossible to distinguish them from the civilians, and even the presence of a weapon was not necessarily a reliable sign. During the civil war, the parties developed fighting forces before formulating a political program, and there were also many criminal gangs in the country, so AKM assault rifles were often used for self-defense. In some cases, it was easier to buy a Kalashnikov rifle on the black market than to get clean water.

The day after Gemayel's death, the IDF occupied West Beirut. The Sabra and Shatila refugee camps were captured by detachments of Lebanese pro-Israeli militants. On September 16, they entered the camps, encountered weak resistance from the people – which was quickly suppressed – and avenging the death of their leader, staged a bloody massacre.

People were shot, tortured, and beaten to death – the massacre was horrible. Various sources claim that from 460 to 3,500 people died, and many more were maimed and raped. By that time, there had already been bloody clashes between Lebanon’s Christian and Muslim communities, and now the Phalanges openly raged against the Palestinians, whom they hated.

Pyrrhic victory

The massacre caused a very strong reaction in Israel. Society demanded an investigation and the resignation of Begin and Sharon. A commission was assembled, headed by the president of the Supreme Court of Israel, Yitzhak Kahan. Kahan, a principled and tough man and excellent lawyer, conducted a thorough investigation and made several conclusions.

Firstly, it was established that the massacre was carried out by Arab Christian militants. Israeli soldiers were not directly involved in it. However, Sharon gave the order to let the Christian militants enter the Sabra and Shatila camps, and no one stopped the massacre. The Kahan Commission placed indirect responsibility for the massacre on a number of Israeli officials, including Defense Minister Sharon, Chief of the General Staff Eitan, and Prime Minister Begin.

Begin's government was forced to resign, and Sharon stepped down as defense minister. These events also impacted the reputation of the United States, which was a guarantor of compliance with the ceasefire agreements. European and American peacekeepers then entered West Beirut and replaced the Israeli troops.

Meanwhile, “peace for Galilee” was still a faraway prospect. Israelis now had to cope with guerrilla warfare and terrorist attacks. The war was no longer popular within Israel itself. The PLO was defeated, but Israel acquired a new enemy in Lebanon – as a result of the war, a new anti-Israeli group called Hezbollah was formed with the aid of Iran.

The new group made a dramatic 'entrance' – on November 11, 1982, a car bomb exploded at the headquarters of the Israeli military administration in the Lebanese city of Tyre. The suicide bomber was a 17-year-old Hezbollah activist. As a result of the attack, 75 Israeli soldiers and intelligence officers and 14 Palestinian detainees were killed. A year later in the same city, a suicide bomber blew up the office of the Israeli Security Agency, killing 28 Israelis and 32 Arabs. In 1983, suicide bombers attacked the barracks of US and French contingents, killing 241 US servicemen and 58 French Foreign Legion paratroopers. An explosion at the US embassy in Beirut killed 63 more. In 1984, Hezbollah militants captured the head of the Beirut branch of the CIA, William Francis Buckley. Buckley was held captive for 15 months, and was interrogated and tortured into revealing the entire network of CIA agents in Lebanon (all of them were killed or went missing). In the end, Buckley went mad from torture and was executed. Hezbollah also abducted four Soviet diplomats. One of them, Arkady Katkov, was shot dead.

In 1983, the Israeli army retreated to the south of Lebanon. There was an exchange of prisoners between the sides – six Israelis were exchanged for 4,700 Palestinians. The Israeli military presence in Lebanon gradually declined.

As a result of the war, Israel lost about 670 people (including about a dozen civilians). The Syrians and the PLO lost up to 3,500 people. The total losses of the Lebanese militant groups and civilians could not be confirmed due to the general chaos of the war, but an estimated 20,000 people died on the Lebanese side.

The political consequences of the war are another issue. The conflict in Lebanon lasted until 1990. A buffer zone was established along the Israel-Lebanon border, but the Israelis eventually closed it down. The PLO was no longer involved in terrorist attacks, and Arafat, instead of falling into oblivion, became the leader of the Palestinian Authority and a Nobel Peace Prize laureate. In reality, Israel only replaced an old enemy with a new one, while Lebanon was devastated by civil war and foreign invasions.

Currently, the situation in Lebanon is still far from stable, and Hezbollah remains one of the most powerful non-governmental groups in the Middle East. All of the above-mentioned events – the successful military operations, the shameful acts of terrorism, and the violence against civilians – have brought the relations between Israel, Lebanon, and the entire Middle East back to their original state. And today the border between Israel and Lebanon is no safer than it was in the early 1980s.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home