Why the UAE needs to scupper a Saudi deal with Qatar

21 November 2019 16:55 UTC |

Abu Dhabi's Mohammed bin Zayed needs conflict to wield influence and without Mohammed bin Salman, he will be a diminished force

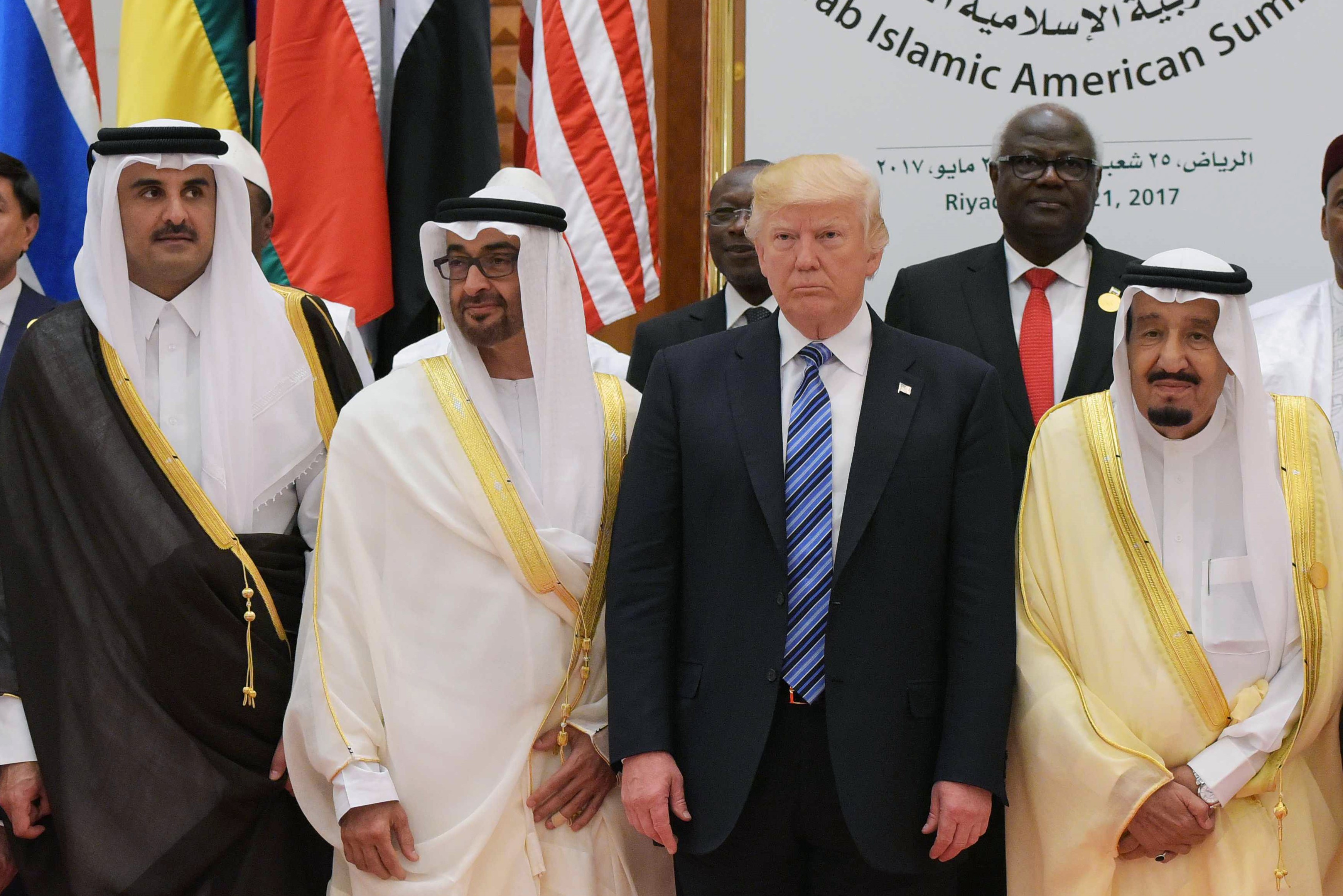

Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (L) meeting with Abu Dhabi's crown prince on 22 November 2018 (AFP)

Two years ago, bloodcurdling threats were made by Saudi and Emirati state-controlled goons about what they would do to Qatar if it did not roll over like Bahrain and become a satellite of their bigger, stronger and wiser neighbours.

They were going to dig a canal along Qatar's land border and dump nuclear waste in it. They were going to do to the emir of Qatar what they did to Egypt's president Mohamed Morsi, who was ousted in a military coup. They were going to turn Doha into another Rabaa Square, where 817 Egyptians were massacred.

A local hero

Physical threats were accompanied by diplomatic ones. In Washington, former administration officials were conscripted to threaten the Gulf peninsula with the withdrawal of the US airforce base at Al Udeid.

The overt threats to Qatar's national sovereignty turned the emir into an unlikely local hero

One such was Robert Gates, who, as a former defence secretary, might have expected to have had some knowledge of the US base in Qatar which serves as a regional hub for US Central Command (Centcom). "MBZ sends his best from Abu Dhabi," the UAE ambassador to Washington, Yousef Otaiba, emailed Gates.

"He says 'give them hell tomorrow'."

The following morning Gates told the right-wing Foundation for Defense of Democracies: "The United States military doesn't have any irreplaceable facility. Tell Qatar to choose sides or we will change the nature of the relationship to include downscaling the base."

Qatar did not blink. The overt threats to its national sovereignty turned the emir into an unlikely local hero.

Two years later

Two years into the blockade, Qatar's economy is stronger; it produces more of its own foodstuffs; it has more friends in Washington - as a result of spending a lot of money there - and Al Udeid is even bigger than it was. Al Jazeera continues to broadcast, recently centring a month of programming around the anniversary of the murder of the Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

Recently, however, the tone of the tweets sent by Mohammed bin Zayed's and Mohammed bin Salman's paid media lackeys has changed. The cue for a change of tone was the decision of the Saudi, Bahraini and Emirati football teams to take part in the Arabian Gulf Cup in Doha, a tournament they boycotted two years ago.

This prompted licensed tweeters to speculate that an end to the blockade was in sight.

"It is no exaggeration to say that there is an intention and a sincere desire to turn the page in the Gulf dispute. The boycott, which is the sovereign right to express dissatisfaction with Qatar's inflammatory approach, served its purpose," wrote Abdulkhaleq Abdulla. "I promise you important developments to resolve the Gulf dispute sooner than you expect."

Or try this backhanded compliment from someone who is no stranger to doing what he is describing.

"One of the windfalls of the crisis with Qatar for some is that while all parties tried to somehow recruit foreign voices as advocates I believe Qatar has spent the most + been remarkably successful in suddenly turning a large number of 'academics and journalists' into advocates," wrote Ali Shihabi.

Change of heart?

What prompted this change of tone and would it really mean a kiss and make up at the meeting of the Gulf Cooperation Council in Riyadh next month?

So far, the Qataris have rejected all demands and the Saudis are - again one has to add so far, engaging on that basis

One possibility which cannot be discounted is that Doha is indeed about to roll over and accept some of the 13 demands made of it two years ago.

These ranged from severing ties with Iran and the Muslim Brotherhood, to handing over "terrorist figures," shutting down Al Jazeera, and "aligning Qatar's military, political and economic policies" with other Gulf states, by which they meant Saudi Arabia.

This, Saudi sources tell me, is not happening. So far, the Qataris have rejected all demands and the Saudis are - again one has to add so far - engaging on that basis. Qatar is not driving this process. Saudi Arabia is.

But why? The blockade has failed to bring a state with an independent foreign policy to heal. The policy of attempting to isolate Qatar has obviously gone wrong. What incentive does Mohammed bin Salman have to end it? To answer that question, we have to look at all the other things that have not worked out for the crown prince.

The Aramco disaster

The most recent disaster is Saudi Aramco. Plans to raise $100bn on a five percent share sale, opening the Saudi market to foreign investors, have been around for over three years.

They came crashing down on Sunday morning. Having failed repeatedly to get $2 trillion valuation he was depending on (the latest consensus was that Aramco was worth between $1.1tn and $1.5tn), the Saudi crown prince ditched the sale of shares on international money markets and announced the sale of 1.5 per cent on a valuation of $1.6-1.7 trillion which would only raise $25.6bn.

Attempting to solve the dispute with Qatar is part of a strategy to rethink where and how all MBS' foreign policy initiatives have gone wrong

Most of this would now be raised locally - presumably by going back to the businessmen whom Mohammed bin Salman had locked up and tortured in the Ritz Charlton in November 2017 and forcing them to buy these shares.

Saudi Arabia's more aggressive foreign policy is not doing much better, either. The kingdom now has a growing list of estranged Arab allies - Jordan, Oman, Iraq. Even Egypt cannot be counted on, and Saudi Arabia has stopped giving it free oil.

Its chief regional enemy Iran is, by contrast, empowered.

Its drones and cruise missiles knocked Mohammed bin Salman's confidence when they slammed into Aramco’s two biggest oil facilities, halving production in an instant.

The attack shook the crown prince, one informed source told me. "He could not have imagined that the Iranians would dare to do this to him. But even worse, he could not have imagined that the Americans would look the other way and do nothing. America has waged wars for less, so how could it have ignored the attacks in this way? Bin Salman now feels vulnerable," the source said.

Since the attack, the Saudi crown prince has been speaking to regional leaders, including Iraqi Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi. They all told him that his problems are his own fault. The Saudi crown prince does not need to speak to Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to know how much damage the October 2018 murder of Jamal Khashoggi - which is still not resolved - has done to the future king's image in the world.

A new strategy

So attempting to solve the dispute with Qatar is part of a strategy to rethink where and how all his foreign policy initiatives have gone wrong. He also needs the money. Qatar is rich and in surplus. All Gulf disputes end one way or another by a ransom of some sort.

All Gulf disputes end one way or another by a ransom of some sort

Another reason for wishing an end to the dispute with Qatar is Israel. A Camp David-style stunt in which the leading Gulf states declare they are normalising relations with Israel has been rumoured for some time.

Mohammed Bin Salman has allowed an increasing number of commentators to defend Israel publicly, even during the most recent attack on Gaza.

If this is to go ahead, the Saudi crown prince needs Qatar to neutralise the negative media that could be created as a result. He will need Qatar to muffle the voice of Palestinians in particular and the Arab street in general.

A bad precedent

There is a precedent for the peace talks currently taking place. Donald Trump initiated a telephone call between the Emir of Qatar Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani and the Saudi crown prince in September 2017. The initiative lasted 24 hours before Saudi Arabia accused Qatar of not being serious about dialogue and suspended communications between the two sides.

The man who persuaded Mohammed bin Salman to call a halt to this was Mohammed bin Zayed, crown prince of Abu Dhabi. Sources say he could very well do the same again.

Note how next month's Gulf Cooperation Council meeting has been moved from Abu Dhabi to Riyadh.

Two years ago, Mohammed bin Salman was more under bin Zayed's control than he is today, after the two countries have diverged over the war in Yemen and over the reaction to Iranian-sponsored attacks on oil tankers and terminals in the Gulf.

Mohammed bin Zayed still holds Mohammed bin Salman on a leash. Although bin Zayed has been the brains - if such a word is appropriate - behind bin Salman's policies, the larger Saudi state has provided the heft. Before each intervention that the Emiratis organised and funded, it was still necessary for regional players to seek Riyadh's blessing.

Thus did the self-styled Libyan Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, who visited Riyadh before launching his attack on Tripoli. So, too, did the then Egyptian defence minister, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, wait for the green light from Saudi Arabia before proceeding with his coup against late president Mohamed Morsi - even though it had been planned in Abu Dhabi.

Parting company

Abu Dhabi needs to hide in Riyadh's shadow until such time as it becomes the de facto ruler of the Sunni Arab world. Mohammed Bin Zayed cannot be faulted for having no ambition.

If peace does indeed break out, it will be the clearest indication yet that the young Saudi prince is parting company with his older Emirati mentor

So, a rapprochement between Saudi and Qatar is not in Abu Dhabi's interests, as it robs them of a much-needed enemy in their midst, a sponsor of "terrorism".

Besides, such a rapprochement would leave Qatar's foreign policy intact and it would thus remain a countervailing force to all bin Zayed's plans for the region from Libya to Yemen.

It is not clear whether this initiative to end the blockade will succeed. Bin Zayed needs conflict to wield influence and without Saudi Arabia, and Mohammed bin Salman in particular, he will be a diminished force.

For this reason, he will do his utmost to scupper a deal with Qatar. But if peace does indeed break out, it will be the clearest indication yet that the young Saudi prince is parting company with his older Emirati mentor.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home