The Last Stand: Israel is very close to breaking a key accord that defined the Middle East

Why a ground operation in the border city would be a violation of the 1979 Camp David peace agreements

By Tamara Ryzhenkova, orientalist, specialist in the history of the Middle East, expert for the Telegram channel ‘Arab Africa’

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s recent statement concerning the plan to evacuate civilians from Rafah and launch a ground operation to eliminate Hamas brigades in the city wasn’t received well by the Egyptian authorities. In fact, Israel’s military scenario has jeopardized the Camp David Peace Accords between Cairo and Tel Aviv. For the first time since they were signed in 1979, the agreements are in danger of being suspended.

Evacuation plan

On February 9, Netanyahu ordered his army to prepare a “plan for the evacuation” of the civilian population from Rafah, which is currently home to 1.5 million Palestinians displaced from other areas of Gaza.

“It is impossible to achieve the war goal of eliminating Hamas and leave four Hamas battalions in Rafah,” Netanyahu’s office said in a statement.

Shortly afterwards, the Israeli Public Broadcasting Corporation announced that Cairo had threatened to suspend the 1979 bilateral peace treaty if the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) launched a ground offensive in Rafah, which is located on the Egypt-Gaza border. The position of the Egyptian authorities was not expressed publicly, but is quite legitimate since the invasion would be a direct violation of the terms of the Camp David Accords.

Peace with Israel

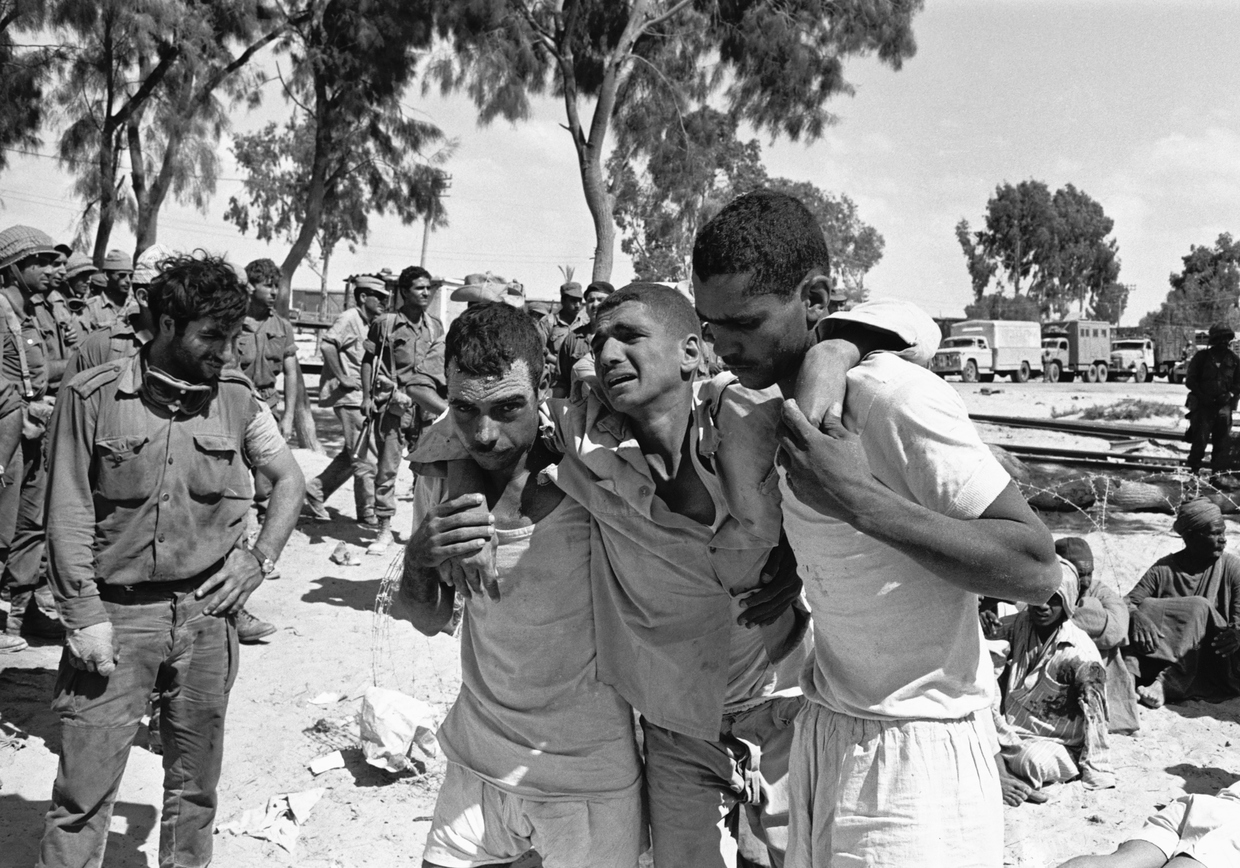

Egypt was the first Arab nation to normalize relations with Israel, having previously been a fierce enemy of the Jewish state. In September 1967, a few years before the Camp David Accords, Egypt was one of the eight countries that signed the so-called Khartoum Resolution, famous for the “Three Noes” (“No peace with Israel, no recognition of Israel, no negotiations with Israel”).

These slogans were largely influenced by the Arab League Summit in Khartoum, which convened shortly after the end of the Six-Day War (June 5-10, 1967), in the course of which Israel swiftly defeated the military coalition formed by Egypt, Syria, Jordan, Iraq, and Algeria. The consequences were quite severe for the Arabs: Israel captured the Sinai Peninsula and the Gaza Strip from Egypt, the West Bank of the Jordan River (including East Jerusalem) from Jordan, and the Golan Heights from Syria.

The Yom Kippur War

In 1970, Anwar El-Sadat came to power in Egypt, and abruptly changed the foreign policy course of Egypt’s former president, Gamal Abdel Nasser. He disbanded the United Arab Republic (a political alliance between Egypt and Syria), refused military assistance from the USSR, and turned to the United States for support.

In 1973, el-Sadat initiated the Yom Kippur War, which aimed to retake control of the Sinai Peninsula. However, the extremely unsuccessful outcome of this military operation forced him to enter into even closer relations with the US and start peace negotiations with Israel.

El-Sadat started talking about a more constructive peace dialogue. In November 1977, at the invitation of Israel, he came on an official visit to Jerusalem and addressed the Knesset, officially recognizing the Jewish state’s right to exist. As it turned out, Egypt – the Arab country with the strongest army – was the first to denounce the “Three Noes” principle.

The Camp David Accords

The historic meetings between el-Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin took place in September 1978 at the US president’s Camp David residence near Washington, D.C.. The meetings were held under the auspices of US President Jimmy Carter and concluded with the signing of two documents intended to establish peaceful coexistence between the two nations.

Six months later, on March 26, 1979, el-Sadat and Begin signed the Egypt–Israel peace treaty in Washington, ending the war between the two nations and establishing diplomatic and economic relations.

According to the Camp David Accords, Egypt regained control over the Sinai Peninsula. In most Arab countries, the treaty was extremely unpopular. The Muslim world believed that el-Sadat had put Egypt’s interests above the unity of Arab nations and had betrayed the pan-Arabic ideas of his predecessor.

El-Sadat seemed proud of his achievement, and declared that he was able to establish peace and regain lost territories without shedding a drop of blood. However, local Islamic groups did not forgive him for establishing peace with Israel, and on October 6, 1981, during a victory parade, el-Sadat was assassinated by conspirators from the Egyptian Islamic Jihad and Al-Gamaa al-Islamiya Islamic fundamentalist groups.

The terms of the agreement

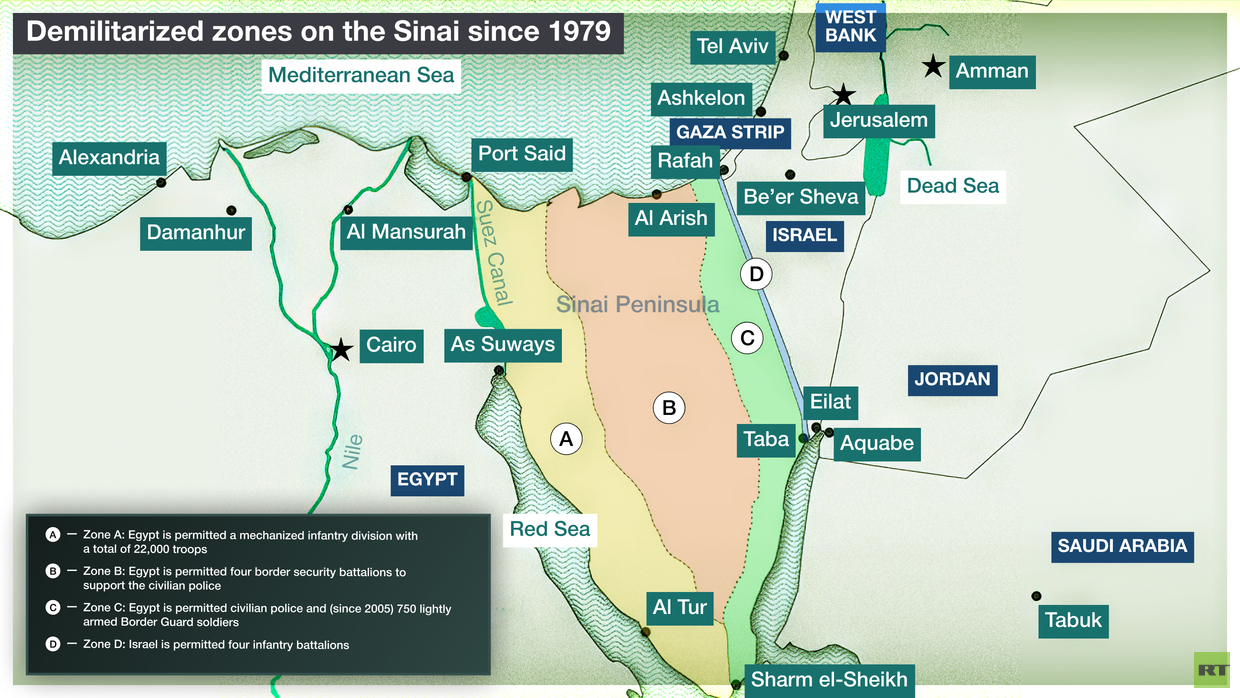

The Camp David Peace Accords clearly stipulated the withdrawal of Israeli forces from the territory of the Sinai Peninsula and regulated any military actions in the area, which was divided into four military zones:

Zone A extends from left to right, from the east coast of the Gulf of Suez to the line marked “A”. Egypt is allowed to deploy one mechanized infantry division with a total of 22,000 troops in this zone.

Zone B is located between lines “A” and “B”. Egyptian border guard units, consisting of four battalions equipped with light weapons and vehicles, are located in this zone. These units provide assistance to the civilian police.

Zone C stretches from the line marked “B” in the west to the national border and the Gulf of Aqaba in the east. Only international UN forces and Egyptian civilian police armed with light weapons can be located in this zone.

Zone D is confined to the national border and the line marked “D” to the west. Up to four Israeli infantry battalions with military equipment, as well as fortifications and UN observation forces can be deployed in this zone.

Since the signing of the accords in 1979, the distribution of forces in zones A and B hasn’t changed, but the rules regarding zones C and D have been adjusted.

Changes and amendments

In 2005, Israel withdrew troops from the Gaza Strip and dismantled Israeli settlements there. At the time, Cairo and Tel Aviv signed the Philadelphi Accord, which stipulated that for the first time since 1979, Egypt was allowed to deploy 750 lightly-armed border guard soldiers on its side of the Rafah border, along a narrow 14-meter-long strip of land located in Zone D, and known as the Philadelphi Corridor or the Salah al-Din Corridor.

However, this agreement was not an amendment to the 1979 treaty. The Palestinian side of the border was controlled by the Palestinian Authority until Hamas came to power in 2007. The Rafah crossing was jointly controlled by the Palestinian Authority and Egypt. It provided limited access for civilians and was used for the delivery of agricultural products to Gaza. After Hamas came to power in 2007, both Egypt and Israel closed the border with Gaza.

In November 2021, Egypt and Israel agreed to add an amendment to the Camp David Accords which would allow Egypt to increase its military presence in the Rafah area. At the time, Cairo was fighting against terrorist groups in North Sinai. However, the exact number of Egyptian troops and military equipment which were allowed to enter the region was not disclosed.

Zone D: Why an Israeli invasion would contradict the terms of the Camp David Accords

Most of the residents displaced from the central and northern parts of Gaza are currently located in Zone D, on the Palestinian side of Rafah.

In this area, Israel can have infantry battalions of up to 4,000 soldiers which are stationed not only along the 14km-long border between Egypt and Gaza but are dispersed throughout Zone D, from the Mediterranean Sea to Eilat. Israel cannot expand this zone, even for training purposes, since this would be a violation of the terms of the peace treaty.

For this reason, the IDF’s potential ground invasion of Rafah directly contradicts the terms of the Camp David Accords. The city, located on the border between Egypt and Gaza, and divided into two parts (the Egyptian and Palestinian side) is part of Zone D. Increasing the IDF’s combat potential in this area without coordinating it with Egypt would be a direct violation of the agreements.

Israel’s plans to evacuate the displaced people is also questionable. Egypt will not allow the Palestinians to leave Gaza. Since the beginning of the war in October 2023, Cairo has repeatedly stressed that it refuses to accept refugees.

Currently, only Palestinians who are seriously ill or wounded, as well as orphans and foreign citizens are allowed to cross into Egypt. Since October, Egypt has fortified the wall on the border with Gaza and also established a field hospital in the village of Sheikh Zuweid, near Rafah.

Construction work in Rafah

Several days ago, construction work started on the Egyptian side of the city of Rafah – the ground is being leveled, and concrete is being unloaded at the site. Due to the secrecy surrounding this construction work, major media outlets have assumed that Egypt is building a buffer zone intended to house the Palestinians during the IDF’s potential ground operation.

Sources from the Sinai tribes report that the construction work is being carried out with the help of engineering equipment belonging to the company Abnaa Sinai (“Sons of Sinai”) owned by Egyptian businessman Ibrahim al-Arjani, who is affiliated with the Egyptian General Intelligence Service. Heavy machinery is clearing large strips of land in Rafah under the surveillance of military forces associated with the Union of Sinai Tribes, headed by al-Arjani.

The debris from the demolished houses is being cleared, and material from a concrete plant also owned by the Abnaa Sinai company is being delivered to the site. The plant produces concrete for the needs of the Egyptian Armed Forces in North Sinai province, and the concrete was recently used to erect a new wall along the Egypt-Gaza border. Egypt also started the construction of enclosed areas with 7-meter-high concrete walls.

Incidentally, in the past few days, Egyptian military leaders have frequently visited the province of North Sinai, and in particular the city of Rafah, and helicopters belonging to the Egyptian Armed Forces and international peacekeeping forces have been regularly spotted near the Philadelphi Axis. Egyptian and foreign officials have also frequented the area and inspected the entry of humanitarian aid into Gaza.

Many residents of North Sinai, especially those of Rafah and Sheikh Zuweid, were evacuated to other areas during the recent war with ISIS, and are now concerned about the condition of their houses, where they hoped to return.

The governor of North Sinai, Mohamed Abdel-Fadil Shousha, expressed the official stance of the Egyptian authorities and denied reports about the construction of a buffer zone. He said the authorities have been making “an inventory of houses that were demolished during the war with the terrorists, in order to provide appropriate [financial] compensation to the owners of these houses.”

He stressed that the authorities do not intend to build camps for the displaced Palestinians and that the operation has nothing to do with the events in Gaza. In other words, Cairo says that it does not intend to deviate from its principles, and will not accept Palestinian refugees.

The reaction of the international community

Meanwhile, the humanitarian crisis in Gaza, and especially in its southern part, has been getting worse. About 1.5 million displaced Palestinians currently reside in the Rafah field camps, while the northern and central parts of Gaza are almost deserted. The Palestinians are cut off from the outside world and depend on limited humanitarian aid. In light of this, Netanyahu’s plan has been strongly condemned by the international community.

French President Emmanuel Macron informed the Israeli leadership that he disagrees with the idea to invade Rafah. Speaking on behalf of the US, National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan made it clear that a ground invasion would be impossible “without a credible and feasible” plan. UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk called the possibility of a full-scale Israeli invasion of Rafah “terrifying.” South Africa urged the International Court of Justice to consider measures that would protect the Palestinian population from a possible Israeli offensive on Rafah, but the ICJ declined the request.

Further developments may not only threaten the mutually beneficial economic relations between Cairo and Tel Aviv, but the two countries may also find themselves on the brink of war. The world’s media is actively discussing this subject, with many outlets reporting that in recent weeks Egypt – which has the strongest army among the Arab nations – has sent additional military equipment to the border with Gaza in order to increase security. According to Reuters, about 40 tanks have already been transported to the border area, and there are also rumors about the deployment of missile defense systems. However, these reports have not been backed by any evidence, especially considering the fact that such measures go against the terms of the Camp David Accords.

If the IDF indeed invades Rafah, Egypt’s reaction may be unpredictable. Although Cairo had fought for the rights of the Palestinian people and the preservation of their territory, in recent years it has maintained the status of a mediator in the negotiations between Israel and Hamas. However, the present situation is extremely dangerous – and while Egypt was the first Arab nation to normalize relations with Israel, it may also become the first to cut these ties.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home