A Small Boy and Israel

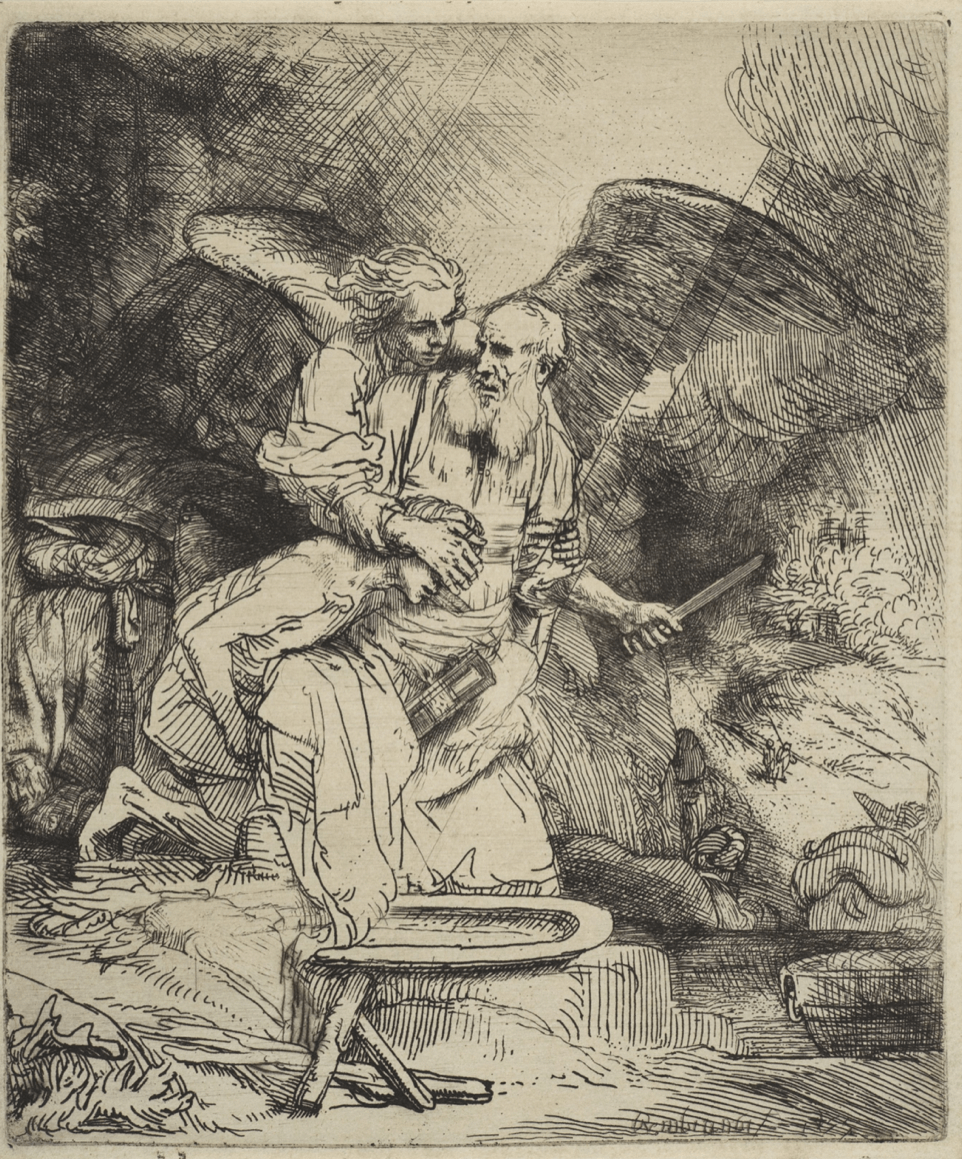

Rembrandt, Abraham’s Sacrifice, 1655. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Understanding the October 7 Hamas attack

The numbers are grim, and the details are worse. 1,400 killed (1100 civilians, 300 troops) and 240 taken hostage. The victims at the Supernova Sukkot music festival were just kids — sweet ones too: lefty, hippie, peaceniks. First, they fled; then they were caught and slaughtered. The other attacks on civilians were equally gratuitous – against children, their parents, and grandparents in their homes. It was like a pogrom by the Cossacks in the Pale of Settlement of Imperial Russia. Or like executions by the Einsatzgruppen and Waffen SS, who followed the German Wehrmacht as it swept through Jewish districts in Eastern Europe during World War II. In each instance, the killings were wholesale and wanton.

Only there’s a difference. In those earlier cases, the Jews were weak, and their oppressors were strong. This time, it’s the reverse. The Palestinians are weak, and the Jews are strong. The Israeli military is the best in the Middle East. It’s as if the Jews of Warsaw in August 1944 escaped their ghetto, crossed the river Oder, and murdered German women, children, teens, and old people – or took them hostage.

But that comparison isn’t right either. Hamas is a state actor, not a desperate militia. They took power in Gaza following parliamentary elections in 2006 and seized full control the following year. Since that time, they have fought off their Palestinian Fatah rivals as well as other Islamic militant groups. Thanks to Israeli transfers, they have lots of money. They also have many weapons. In addition to truck-mounted machine guns and small arms, their militants can fire long-range rockets, mortars, and grenades. They have access to improvised explosive devices, drones, and anti-tank missiles. They built and control an extensive network of tunnels and deploy cyber-assaults and espionage. On October 7, they mounted simultaneous, complex attacks on multiple Israeli military guard posts and crashed vehicles through border fences and other barriers to reach their targets. They had physical maps and electronic communication to guide them.

The U.S. State Department designated Hamas a terrorist organization in 1997. In 2001, a Hamas operative placed a bomb in a Tel Aviv disco, killing 21. During the following two decades, bus bombings in Israel killed and wounded hundreds. But to call Hamas a terrorist group is wrong for two reasons. First because the group is more like a well-trained army, as we have seen, than a network of fanatic bomb throwers. And second, because use of the term “terrorist” whitewashes the much greater mayhem perpetrated by powerful states. When the U.S. bombed civilian populations – as it did in Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, El Salvador, Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, El Salvador, and even Grenada — it claimed raison d’etat and mostly escaped reprobation or sanction. With U.S. support, Israel is currently bombing the densely populated Gaza Strip. More than 10,000 civilians have been killed so far, according to Hamas, more than a third of them children. The U.S. and its allies – including Israel — comprise what Edward S. Herman in 1983 called “the real terror network.” America’s victims number in the millions. Israel, whose victims number in the thousands, is an epigone. Hamas is a piker.

Whether conducted by the United States, Israel, Russia, Palestine, or dozens of other states or non-state authorities, war today is a version of terrorism. Little distinction is made between combatants and non-combatants, and legal determinations of responsibility are generally made, if at all, after the fact, by the victors. “There will be plenty of time to make assessments about how these operations were conducted,” U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken blithely stated on November 6. The whitewash has already begun.

Hamas’s attack on Israel was reprehensible. It was also consistent with modern warfare, and was conducted for a reason; to prevent a possible treaty – an expansion of the Abraham Accords — to normalize relations between Israel and Saudi Arabia. Such an agreement would have ignored the Palestinian struggle for emancipation and further isolated Iran, one of Hamas’s allies. Hamas surely knew their attack would lead to fierce Israeli reprisals, possibly even an invasion. But they calculated that whatever the cost, it was worth it. When the war finally ends, Israel may be more willing than before to negotiate a solution to the long, bloody dispute over Palestine. Indeed, the higher the death toll on both sides, they probably reasoned, the more likely an accommodation. They may be mistaken, however. Post-war conditions could wind up little changed from pre-war ones, except with many thousands of Palestinians dead, hundreds of thousands more homeless, and Israel or its Mideast allies policing Gaza.

A Yeshiva boy

Every American Jew learns about Israel in childhood. I don’t remember much about my first exposure, but it must have come in the context of a family discussion (this would have been in the early 1960s) about Jewish identity and anti-Jewish prejudice. If we saw a movie or TV program with a Jewish actor or entertainer — Tony Curtis, Kirk Douglas Dinah Shore, Woody Allen – that fact was mentioned approvingly, unless the person was considered low brow, like Milton Berle or Danny Kaye, in which case there would tongue clucking. If a right-wing or Republican politician was seen or mentioned – Barry Goldwater, Richard Nixon, George Wallace – it was followed by the (usually accurate) words “anti-Semite.” That’s when the state of Israel might have been invoked. It was the place where Jews were safe and respected, and where they could find sanctuary if things in the U.S. went sideways.

The “Law of Return,” passed in 1950 by the Israeli Knesset was a stroke of marketing genius. Jews all over the world were at once granted a second nationality and a place of real or imagined refuge – Palestinians be damned. The rank injustice that we could “return” to a territory we never inhabited, while Palestinians were barred from returning to the land from which they had been recently expelled, never entered our minds. And even if it had, we’d never have demanded that sovereignty over the land of Israel be shared with the exiled Palestinian population. Our anti-Arab prejudice was exceeded only by the strength of our memories. The Holocaust was less than a generation distant, and we knew lots of survivors. There was the Hungarian, silver-haired Mrs. Block, in apartment 2R below us; the cheerful Mrs. Schlesinger, and her dog Socrates who had his own phone number – you could look him up “in the book”. And there was the tall, austere doorman; because he was Polish and gentile, we were admonished to approach him with caution. I was once reprimanded by my mother for asking him about the blue numbers on his arm.

In 1966, I started yeshiva – an orthodox after-school program at tiny Temple Shalom in Forest Hills. I was sent there because it was close and cheap. If I stuck with my lessons, I’d be prepared three years later for Bar Mitzvah. I enjoyed learning Hebrew, which I was wrongly taught was the historic language of the Jews. (Between about 200 to 1900, it was solely a liturgical language; it was revived by Zionists.) But regular religious worship was uncongenial in the extreme. Nobody in my family believed in God or regularly attended services, not even my grandparents from Eastern Europe who still spoke some Yiddish. From my earliest memory, I was a proud atheist.

The only pious student in my yeshiva class was Samuel or Shmu’el. He was small for his age and wore thick glasses. He refused ever to say out loud the word “God” because it was too holy, so instead he’d substitute “Hashem” (Hebrew for “the name”). We taunted him by pulling a nickel from his ear and asking: “What’s that written to the left of Thomas Jefferson’s nose?” He’d stammer gamely: “In Hashem w-w-we, trust”. Or we’d stop him on his way home and ask: “What’s that song Kate Smith always sings?”. “Hashem Bless America” he’d answer. We were smart kids, and good at school, Shmu’el included. We followed political events and knew some history, but we never discussed – or knew anything about – the Nakba or “catastrophe” that befell Palestinian society and made possible the state of Israel. Between 1947 and ’49, some 750,000 people from a population of 1.9 million were displaced, 15,000 killed, and 530 Palestinian towns and villages destroyed.

During the Six-Day War in June ’67, we returned to the yeshiva – even though school was out for the year– to closely follow developments. I recall Rabbi Sanders standing in front of a chalkboard, erasing the x’s and y’s that stood for Egyptian planes and tanks, and tallying up the dead Syrian, Jordanian, and Egyptian soldiers. When Israel quickly prevailed, we celebrated as if the last-place New York Mets had won the World Series, which they would do two years later. We exulted in the territorial expansion of the Land of Israel and couldn’t care less about Palestinian civilians killed, injured, or displaced.

It would be at least a decade or so before I began to doubt the righteousness of Israel. The key event for me was the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982, followed by the Sabra and Shatila massacres, carried out by Lebanese Christian militias with the tacit approval of the Israeli Defense Forces. The succession of Israeli blockades and attacks upon Gaza between 2007 and 14 confirmed my view that Israel was an occupying power, determined to enforce a policy of apartheid. The long rule of the corrupt and incompetent President of the Palestinian Authority, Mahmoud Abbas; and the incompetent and corrupt Prime Minister of Israel, Benjamin Netanyahu, made the current war inevitable. Today, Netanyahu and his neo-fascist regime have alienated many American Jews who were once Israel’s strongest supporters.

American Jews’ attachment to Israel

Some Jews and many Gentiles (e.g. Donald Trump) think the bond between American and Israeli Jews is natural and inevitable, even atavistic: based on blood or race. That’s nonsense, of course. Judaism is a religion, not a race, and anyway, there’s no such thing as biological race. (The validity of the category was first disproved by Franz Boas in 1928.) The Jewish diaspora doesn’t even have a common lineage. Ashkenazi Jews (those from Central and Eastern Europe, currently about 70% of the total) are genetically heterogeneous and have little connection to the Jews of the ancient Near East. A study in Nature Communications, suggests that modern Ashkenazim originated in pre-historic Europe, not the Levant. In other words, the genetic origin of most modern Jews was not Jewish!

A more common belief is that American Jews revere Israel and Zionism because of cultural and religious solidarity. The position is understandable. American Jews number only about 7.5 million, or just 2% of the total U.S. population, with half those in New York and California. My chance of accidentally meeting another Jew while driving across the U.S. from Micanopy, Florida where I live, to the California border is exceedingly small. In rural Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona, synagogues are harder to find than electric vehicle recharging stations.

In fact today, except for orthodox and Hasidic sects, American Jews are no more Zionist than non-Jews. It’s evangelical Christians, Christian Zionists and dispensationalists who are the most fervent supporters of Israel, and that’s because they see the state as fulfillment of biblical prophecy, and the future site of the “Rapture” when Jews will be cast down to Hell and Christians ascend to heaven. The new U.S. House Speaker Mike Johnson of Louisiana is a dispensationalist who believes that during the final stage of historic development, or “dispensation,” the world will be destroyed by flames and Christ will return to Israel to establish a new heaven and earth, populated by those who have been born-again. Johnson is a supporter of Israel and backs a new package of military aid – so long as the money comes from the budget of the IRS, revealing the limits of his faith; the tax man is more feared than the Messiah is desired.

The real basis of American Jewish attraction to Israel is fear of anti-Semitism in the United States. The concern is not trivial. Jews were shunned, opposed, and oppressed from their very first arrival in the American colonies. Peter Stuyvesant, governor of New Amsterdam (later New York) called them “enemies and blasphemers” and tried in 1655 to bar Jews from emigrating to the colony. Then, when some came anyway, he levied a special tax on them. Two centuries later, General Ulysses Grant issued an order expelling Jews from southern territories under his control. (Lincoln rescinded the order.) During and after the surge of Jewish migration from Eastern Europe, between about 1880 and 1920, anti-Semitism in the U.S. significantly increased. Jews were discriminated against in employment, education, and housing, denied membership in private clubs, and “restricted” from many hotels and restaurants.

The lynching of Leo Frank in Atlanta in 1915, after his unjust conviction for murder, marked a new low point in Jewish-American life. The killing precipitated the revival of the Ku Klux Klan and the wide dissemination of anti-Semitic attitudes during the interwar years, promoted by such prominent figures as Henry Ford, Charles Coughlin, and Charles Lindberg. Polls at the time indicated that strong majorities of Americans found Jews “greedy,” “dishonest” and “pushy.” It would take a world war and widespread revulsion of Hitler and the genocide of Jews, to generally break the spell of U.S. anti-Semitism. Nevertheless, a recent survey by the ADL indicates a significant rise in anti-Semitic attitudes. Though the poll is flawed – it essentially equates anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism – Jews themselves detect an increase in anti-Jewish attitudes and behaviors.

Among the many tragedies of the October 7 Hamas attack, and Israel’s program of retribution, is that they may strengthen American Jewish and Evangelical support for the country, assuring continued U.S. military and diplomatic aid for the most racist and expansionist government Israel has ever known. That makes the case for an immediate ceasefire and peace negotiations even more urgent. At stake is the survival of the Palestinian people and the reconstitution of Israeli democracy.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home