The Greatest Film Never Made

Decades before "Oppenheimer" a movie that might have made a difference was prevented by a U.S. cover-up.

Reprinted with permission from Greg Mitchell’s newsletter Oppenheimer: From Hiroshima to Hollywood.

Here are some updates and links, and crucial background, related to my recent film Atomic Cover-up and the newly-updated book of the same title – what might be called the post-Hiroshima story (and with actual bomb survivors) left out of Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer.

My 2021 film, which has appeared at 20 film festivals around the world and won three awards, is now available for free via Kanopy, if you have any sort of library card or school affiliation. It will also be coming to PBS and PBS.org, probably late this autumn. Right now it is available for purchase or rental for schools, community groups, or individuals from The Video Project. Here is the web site for the film, where you can watch the trailer and read background and dozens of responses from various notables.

The book, meanwhile, now has thousands of new words in its update, mainly on my response to the Nolan film going back to mid-July. It’s available in paperback but also on sale this week as an ebook for just $3.99. And just received first offer for a Japanese translation.

Now, what’s it all about? See below. And you can still subscribe to this newsletter for free.

Let’s begin with my film in a nutshell, then we’ll explain how it got rolling.

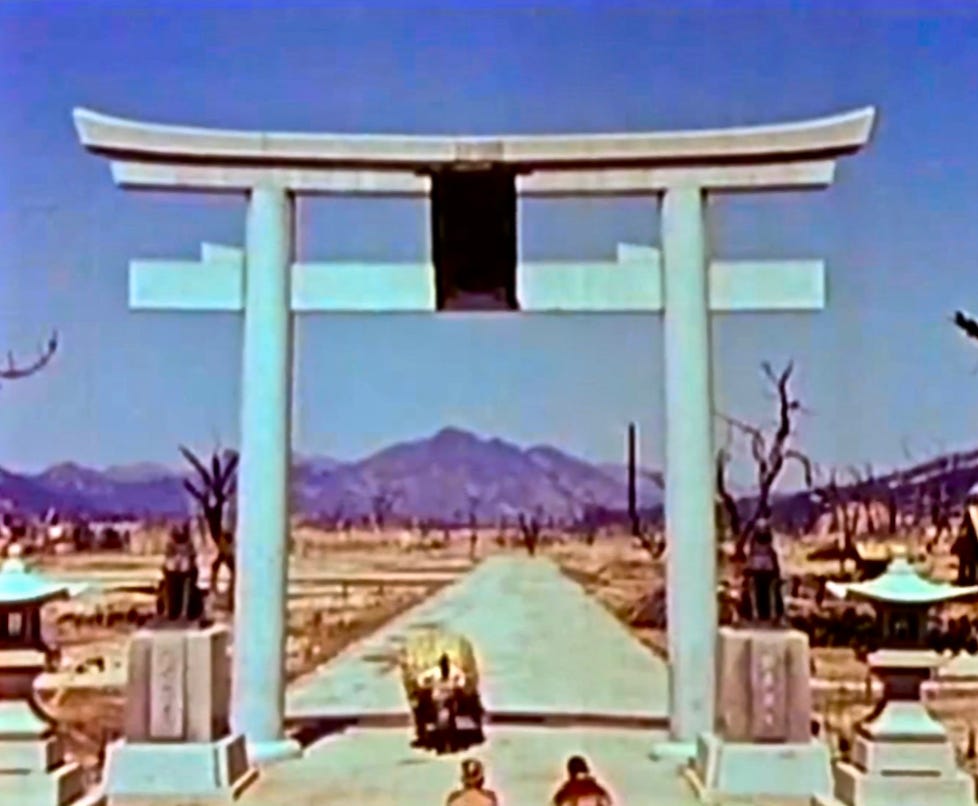

Atomic Cover-up is the first documentary to explore the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 from the unique perspective, words and startling images of the brave cameramen and directors who risked their lives filming in the irradiated aftermath. It reveals how this historic footage, created by a Japanese newsreel crew and then an elite U.S. Army team (who shot the only color reels), was seized, classified top secret, and then buried by American officials for decades to hide the full human costs of the bombings as a dangerous nuclear arms race raged. All the while, the producers of the footage made heroic efforts to find and expose their shocking film, to reveal truths of the atomic bombings that might halt nuclear proliferation. Atomic Cover-up represents, at least in part, the film they were not allowed to make, as well as a tribute to documentarians everywhere.

Now, how did I “get that story”?

It began for me back in June,1982. That day also set me on the path to spending four weeks in Hiroshima and Nagasaki soon after, and subsequently writing three books on the subject, hundreds of articles, and the film premiering today.

That spring, the grassroots antinuclear movement in the U.S. (and much of the world) was cresting. The June 12th march and rally in New York City would draw well over half a million protesters, perhaps the largest such gathering in the country’s history. Many new films with nuclear themes suddenly appeared, including the popular Atomic Cafe.

As someone who came of age in the 1950s and 1960s, I had experienced the terror of the most dangerous years of the nuclear arms race, and Dr. Strangelove was my favorite movie. But I had never attended an “anti-bomb” rally, as I was more interested in protesting the Vietnam war, various environmental hazards and, after Three Mile Island, nuclear power. My knowledge about the dropping of two atomic bombs over Japan in 1945 was only skin-deep.

But one day in June 1982, I took notice when my wife spotted an item in The New York Times revealing that the Japan Society in New York would be screening the first movie drawing on film footage shot in Hiroshima and Nagasaki by an elite American military team, then suppressed for decades. One of the officers who was a key component of that team would discuss this for the first time. I was a member of the Japan Society – they had even arranged my recent interview with Akira Kurosawa – and always loved a good “U.S. cover-up.” So we decided to attend the event a few days later.

The film, produced in Japan, was called Prophecy. That former Army lieutenant, who went on to a long career as a producer/director in the emerging television industry, was named Herbert Sussan. He described being recruited near the end of 1945 to join a major U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey project to shoot the first and only color footage documenting the destruction of Japanese cities from the air during the war. It seemed like a free, triumphant, travelogue for the young man until they arrived by train at their first stop, Nagasaki. He would be haunted by what he saw there, and then in Hiroshima, for the rest of his life.

I suppose, no doubt to a lesser degree, I could say that I would be haunted by his words, and the film we would soon see, for the rest of my life. (Sussan, below, with photos taken during his mission.)

Sussan described filming, in blazing color – rarely used by documentarians at the time – the badly injured, burned or sick-from-radiation patients in hospitals. (The cameraman, amazingly, was often Akira “Harry” Mimura, a Hollywood veteran who had also shot Kurosawa’s first film.) Sussan realized that Americans back home, to this point, had only been allowed to see grainy, black and white images of rubble in the atomic cities, not the victims, who were mainly women and children. When he returned to New York, he was determined to show the world what he experienced, feeling that this might halt the building of bigger weapons and prevent a dangerous nuclear arms race with the Russians.

Instead, he found that all of the footage had been classified top secret and buried by the U.S. military, and none of it could be shown to the public. The color images were just too revealing, not only exposing unfathomable physical destruction but the long-lasting damage to human bodies (overwhelmingly civilians). Seized by the U.S. and hidden at the same time was all of the searing black and white footage shot earlier by the leading Japanese newsreel company, Nippon Eiga Sha.

Sussan tried for thirty years to find and make use of his footage – Americans still had not been exposed to color images of any kind from Hiroshima and Nagasaki – but got nowhere, even after personally approaching everyone from famed newsman Edward R. Murrow to former President Harry S. Truman.

Finally, he would, almost by accident, play a central role in the footage becoming known to the world. Around 1979 he attended an exhibit of photos from the atomic cities at the United Nations near his apartment. To his dismay, he spotted several color enlargements of frames from the footage his team had shot in early 1946. He said to a Japanese man, Tsotumu Iwakura, who had helped arrange the exhibit, something to the effect, “I shot the footage this photo is taken from.” Imagine Iwakura’s surprise. Iwakura did some digging at the National Archives in Washington and discovered that the color footage had been declassified, very quietly, a few years earlier. If no one knew about this, it was just the same as still being classified.

Iwakura went back to Japan and launched what became as the “10 Feet Movement,” a grassroots project whereby people (including school kids) could raise and contribute funds to buy back copies of all of the color footage in increments of ten feet. When they reached their goal, he made it available to Japanese filmmakers, who soon completed two documentaries with more in the works. The creators of the film that I saw, Prophecy, were able to track down some of the survivors shown in the 1946 footage and then contrasted the often horrid images of them then with current footage and interviews. Soon Americans started making use of the color footage–although only in brief passages–in their own films.

Sussan was gravely ill (one of his doctors told him it was possible that his lymphoma stemmed from radiation exposure in 1946), and the antinuclear movement began to fade. But my own interest had been sparked. Later in 1982, when I became the editor of the leading American magazine for that movement, Nuclear Times – David Corn was one of the magazine top writers and editors – the first feature I assigned was on Herbert Sussan. I would join in the interview, and become a friend.

I would also track down in California and interview the man who led that filming project, Lt. Col. Daniel A. McGovern, who sent me many unclassified documents (some appearing in my film for the first time). On why the footage was suppressed, McGovern informed me that officials and the military “were fearful because of the horror it contained. …because it showed effects on men, women and children…They didn’t want that material out because they were working on new nuclear weapons.” I would also talk with Erik Barnouw, the legendary writer on documentary films who in 1970 had created the first film to make use of the long-suppressed black and white Nippon Eiga Sha footage, Hiroshima-Nagasaki 1945.

Aiming to gain a firsthand experience, I secured a journalism grant to spend a month in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, meeting some who had been filmed by Sussan and McGovern. Then I wrote articles on various aspects of that trip for The New York Times, Washington Post, and Mother Jones, among others. I would even interview Paul Tibbets, the pilot of the Enola Gay which deposited the bomb over Hiroshima, and meet his counterpart on the Nagasaki mission, Charles Sweeney. (McGovern in Nagasaki, below.)

A decade later I included a small section on the color footage in my acclaimed book with Robert Jay Lifton, Hiroshima in America. My writings on that would spark the making of the award-winning film Original Child Bomb in 2004. As a consultant for that film, I was able to finally view (via VHS copies) all of the color footage. A few years later, I wrote my book about the saga of the footage, Atomic Cover-up.

Finally, three years ago, I set out to finally fulfill the vision I had, decades ago, of paying tribute to those who shot both the Japanese newsreel and U.S. military footage in 1945-1946. I arranged for the first 4K film transfers of the Japanese footage and the same for several reels of the color footage from the National Archives. I also obtained the relevant portions of books by or about several of the cameramen and producers of the Japanese footage, and the memoir of Harry Mimura, and had key sections translated from the Japanese for the first time. This provides the most revealing account of the Japanese side of this story to date.

Some of the footage in my film has never been aired before, and everything is in 4K. As noted, Atomic Cover-up would be selected for festivals around the USA and abroad (Berlin, Rio, Tokyo, and more), and hailed by numerous well-known writers and filmmakers. Trailer here:

Atomic Cover-Up TRAILER from Suzanne Mitchell on Vimeo.

The Byrds may have lost Gene Clark at this time but somehow they managed to latch on to a Nazim Hikmet poem that explicitly relates to the Hiroshima bombing – not a great song by any means but still the most “explicit” by a major group on this subject.

Thanks for reading Oppenheimer: From Hiroshima to Hollywood! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including “Hiroshima in America,” and the recent award-winning The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood – and America – Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, and has directed three documentary films since 2021, including two for PBS (plus award-winning “Atomic Cover-up”). He has written widely about the atomic bomb and atomic bombings, and their aftermath, for over forty years. He writes often at Oppenheimer: From Hiroshima to Hollywood.

https://www.antiwar.com/blog/2023/09/29/the-greatest-film-never-made/

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home