Art – Awakening – Abolition

The cover of Janie Paul’s Making Art in Prison: Survival and Resistance (Hat and Beard 2023) shows a painting of a man in prison who stares at us. We see him on the other side of wire. In the background behind him are ten other prisoners in the yard. The artist is Rafael DeJesus. The man stares implacably. Neither vacant nor accusatory the expression is sad though not quite accepting. It is alert, as if to say to us, “your move.”

Rafael DeJesus, Orange Nation.

Our move must be abolition.

Why this is so is partly explained by another prison-artists, John Ortiz-Kehoe, who writes of his painting “Under the watchful eye of a guard tower, I fight to exist.” He explains, “No longer a man … identified only by number… 256263 … property of the state of Michigan …. A 13th Amendment slave sentenced to die a slow death by way of imprisonment, the true meaning of a life sentence. Spittin’ dirt on my name … heap that dirt on my grave. I’ve been buried alive! (I can’t breathe!) And as each day passes, I become more consumed by the metal bar and razor wire that constrict around me like an iron python. How long can I last? Clutching my heart trying to save my humanity. It’s more than brutal, this is Death by Incarceration.”

“Let’s say we’re in prison” proposes Nazim Hikmet in a poem introducing the book. It concludes, “We must live as if one never dies.”

A remarkable prologue imaginatively summarizes everything that follows. Written in the second person (“Perhaps you landed in prison because you wrote bad checks or couldn’t stop shoplifting”) it puts us in the shoes of the prison artist who has lost everything cherished and taken you from “the world.” She describes becoming an artist in prison. The quintessence of freedom in the quintessence of unfreedom. It takes you to the encuentrobetween inside and outside thanks to the Prison Creative Arts Project (PCAP) founded by the late Buzz Alexander at the University of Michigan.

Doing time, hard time, are expressions for the deprivation of the prison. Her prologue ends with an artist reflecting on “a memory of Lake Michigan in the early morning with light on the red, red rocks so many millions of years old.” That’s a geological perspective on time. Thoreau brings consciousness or human subjectivity to the subject of time in the last sentence of his book, Walden, “Only that day dawns to which we are awake.”

Art can awaken.

Art awakens the artist and awakens those on the outside who see it. This book continues the awakening on both sides of the prison walls. It is important that it is the artists who are awakening us. Janie Paul writes, “The crux of the whole book is the validation from PCAP and other inside artists supporting the awakening of the spirit through art; awakening what is already inside the artist and needs to be brought out. This is NOT rehabilitation. We are not “fixing” someone. In this moment the artist is realizing the possibilities and the future that he has as a creative person.”

This book is a continuation of a process that includes the annual exhibit, correspondence, and video of the work of prisoner artists at the twenty-eight Michigan lock-ups. The prologue breaks down that separation between prison and the world. They talk technique, they talk resources or materials, they talk subjectivity, they talk philosophy. Paolo Freire and Miles Horton who believed social salvation was collective and that it comes from below inspired the project.

Printed in Slovenia under the watchful eye of the author, the book is handsome with cloth cover, orange ribbon page marker, elegant feel to the paper stock. It lies flat on the table opened at any page. Holding a handful of pages, they are easily fanned as the thumb releases them without creasing the paper. The colors are true to the originals. A hundred and four artists are included, or a hundred and five counting Janie Paul, an artist herself. There are at least two hundred twenty full color illustrations.

There are sixteen stories written by different artists. The first one is by Alan Compo, half Native and half white. It is frank about building himself up or about taking himself down, but always reflecting. His art is Introspective, symbolic, and full of the humor of his Native culture. “We laugh at ourselves a lot, and really the entire process is so overwhelming that in our odd prisoner way, [it] is very humorous.” Susan Brown who also identifies as native shares that humor with a comparison of the Michigan prisoner to a ten point buck all expressed in bead work!

John Bone provides the next story. He provides another visual vocabulary entirely – black and white, representational, documentary and almost photographic. The hard and rigid structures of life – the bars, the steel, the bars, and more bars. Now we see the cages. The cell block, the cell scene, the corridors. Overhead, florescent light. Confinement. For days, weeks, months, years, a life. A depressing, grim vision leads us to this dreary, cruel world.

John Bone, Cell Scene.

After these two stories twelve pages follow with simple and bold assertions explaining the subtitle Survival and Resistance with a couple of paintings accompanying each proposition.

+ Artists resist displacement with images of home, belonging, and community.

+ They resist tedium with mystery and humor.

+ They resist being identified by a number with images of themselves and their heritage.

+ They resist separation from family and loved ones with images of love and affection.

+ Artists resist apathy with critiques of the United States.

+ Artists resist despair with images that express their sources of faith.

+ They resist sterility with images of landscapes and wildlife.

+ They admire heroes, display technical virtuosity, and create beauty, pleasure, and joy.

Janie Paul emphasizes feeling, the feelings of light, of landscape, of shades and shapes. She draws attention to how the artist conveys texture. On one level this is a technical matter of materials, paper, brushes, paints, and on another level it verges directly on philosophy as when John Berger writes of the prisoner’s “particular sensitivity towards liberty, not as a principle, but as a granular substance.” Feeling might refer to an emotional state obtained by behavior or a memory or it might refer to something tactile or palpable, obtained via ‘the five senses.’ Art work combines these two meanings of feeling. Texture is important to artists because there are few textures of life in prison – rather there is plastic, concrete, and metal. Meaning may be found in the granularity of the visual and physical elements of art. Meaning is realized in form as well as content.

Janie Paul puts the prison art in a framework that begins in the concentration camps where Victor Frankl learned that those who found some meaning to life were more apt to survive than those who did not. Where health and survival depend on “meaning” the difference between subject and object necessarily disappears. The other part of the framework comes in the conclusion where our lives – humanity as such – depends on having a sense of the future, a horizon. She quotes John Berger (1926-2017). “There is something even more fundamental than sex or work … the great universal, human need to look forward. Take the future away from a man and you have done something worse than killing him.”

Frankl spoke from a central experience of the 20th century the concentration or death camps. John Berger wrote from a related experience, the anti-imperialist movement of peoples. It is no wonder that Berger came to find the prison the perfect metaphor for the 21st century. Berger writes with the suffering authority of Job or the prophecies of Isaiah. It is well to recall that when the carpenter’s son opened the scroll to read Isaiah’s injunction to release prisoners, he was threatened with being tossed over a cliff and was thrown out of town instead (Luke 4:29). So much for Jesus.

The poet Jimmy Bacca provides an unforgettable image from his own experience of the smug attitude similar to Jesus’s home-town neighbors. Shackled and hobbling to the bath room on a road trip to prison, Bacca passes “passive ranchers and glum truckers’ faces turned down to their coffee and plates of sausage, scrambled eggs, and toast. …. To them, I was a criminal without soul, heart, or feelings.”

My introduction to American prison was earlier with the New England Prisoners’ Association (1973-1975), with Joseph Harry Brown doing long hard time at the Federal Penitentiary in Marion, and with teaching at Attica penitentiary. We published a newspaper, one of many in those years of the prisoners’ movement. I persuaded my fellow editors to publish a supplement on Hogarth’s twelve engravings of 1740 called “Industry and Idleness.” Of course, they didn’t have movies in the 18th century but a series of engraved pictures was an approximation of narrative movement. There was a tremendous realism in the depiction of the social origins of crime despite the ostensible moralism of the twelve engravings whose overall message was simple – work or be hanged. That was in the era of the Atlantic slave trade. I wanted to show how capital, crime, and class were inter-related. That was my attempt to teach prisoners about capitalism using the medium of art. In contrast this book is of artists teaching us from the habitat of prison. I wanted to understand capitalism, they want to understand what it is to be human. It is in a book such as this that the two questions – what is capitalism? what is human? – can conjoin.

Look at the pointed and gentle humor of Lionel Stewart, or A. Marjani’s pretty doll, “Convict Barbie,” or the pudgy pictures of Martin Vargas. Check out the epic works of allegorical and Biblical drama of Duane Montney. Contemplate the masterful visual statements of dehumanization, using prisoners as disposable used-up commodities, of Bryan Picken.

Bryan Picken, Confiscated Goods.

Danny Valentine’s astonishing skill in materials, turning toilet paper somehow into pewter in an extraordinary sculpture of a mermaid, so real that it might flap its tail and swim off the page.

Danny Valentine, Pewter Mermaid.

In Oliger Merko’s riotous enjoyment of color, the temperature of his painting are warm, hot, sweltering. His brush is soaked through with paint, its stroke applies the paint with abandon. His “Pieta” is an agony of orange and blue, compassion and suffering. They are complementary colors and also the color of the prisoners’ uniform: sky, earth, and people, as if to say that there is no outside, no free world. Art provides “a real second life – more than an escape,” Merko says.

Oliger Merko, Pieta.

Billy Brown’s visual vocabulary, “Billy art,” he called it, consists of thousands of pencil strokes which create the illusion of the physical presence of an embroidery. The joy of making patterns, the meditative practice of pencil markings. The versatile Andy Wynkoop can span a range from his loving portrait of his sister to a terrifying dystopian image alluding to the book of Revelation 6:8. “And there as I looked was another horse, sickly pale; and its rider’s name was Death, and Hades came close behind. To him was given power over a quarter of the earth, with the right to kill by sword and by famine, by pestilence and wild beasts.”

Everywhere there is lyricism, reverie, and dream. Merko’s Imaginary Cello, Wynn Satterlee’s Free Hats, Yoshikawa’s vertical triptych, American Dream, Curtis Dawkins, Whatever You Want It to Be. It is all worthy, as Dostoevsky might say, of the suffering.

Paul Gaughin asked in one of his paintings in Tahiti, “Where Do We Come From? What are We? Where are We going?” Similarly, basic ontological questions asked of and by the prison artists, Who am I? What do I do? How do I create meaning? Such questions lead to reflection and to growth. This is not to say it is all therapeutic. It is pleasurable, it is possible, and it is profitable. It is the inside or outside grounding of spiritual, psychological, social, and political change. The questions of philosophy easily and necessarily become questions of social change. Gaughin’s questions lead to the critique of settler colonialism, Janie Paul’s to the critique of capitalism itself.

Her book provides evidence of life in prison in the midst of neo-liberalism. That evidence also raises the question Marx raised: what is a human being? This was and remains the direct opposite to the capitalist’s logic which separates and divides based on the ridiculous dominating power that imposes punishment as the consequence of crime when the actual crime is the prison and all it signifies of enclosures, evictions, extractions, and expropriations.

She might as well have quoted Eric Fromm or Herbert Marcuse because they too wondered, analyzed, and questioned what is it to be human? Marxist humanism abides in The 1844 Economic & Philosophical Manuscripts, first translated in 1947 by Grace Lee Boggs. These manuscripts provided an escape from the nihilistic possibility that always lurked within existentialism which infamously countenanced the murder of an Algerian. Marx went from the critique of philosophy to the critique political economy.

The artists practice a kind of inner freedom that creates little communities within prison, outside prison, and between inside and outside. Janie Paul writes of “the deep inner space of generative imagination,” a hidden geography constructed by miles and miles, hours and hours on the road to nearly thirty state prisons.

In 1977 the prisoner poet, Jimmy Santiago Bacco, wrote “Healing Earthquakes” which concluded with lines anticipating the Native slogan of “Land Back.” He wrote of

A man awakening to the day with a place to stand

And ground to defend.

The theme of awakening must be grounded. His people were Indios or of Spanish, Aztec, and Maya, who had lost their ground, and in consequence he had lost his way. In prison a Chicano gangster with slicked-back black hair and blue oval sunglasses, ever ready to kill or be killed, became his guide and teacher – “once they make you forget the language and history, they’ve killed you….” “The key was to survive prison, not let it kill your spirit, crush your heart, or have you wheeled out with your toe tagged.” Jimmy Bacca wrote, “In a very real way, words had broken through the walls and set me free.”

Art breaks through the walls.

The study of history makes possible a long view. This is the moment of expropriation, the moment of the prison. This was the moment of Marx’s turn to the critique of philosophy, and his anthropological, economical, philosophical, approach to the human being who, as a human being, becomes a proletarian. Enclosure was not only a technical process of privatization of land, it was also the birth of the penitentiary and its moralism establishing logic between crime and punishment when in actuality the two have different determinations.

Crime became a mode of working-class survival, punishment is a mode of ruling-class terror. Thus the logic of crime and punishment is nothing else than the historical struggle between the classes, those who have and those who don’t.

Janie Paul writes, the “freedom to choose is incredibly significant in a world where so much is determined by others. Perhaps the most important choice is the claiming of oneself as a subject rather than as an object, as a person who acts on, not a person who is acted upon. In the United States, incarcerated people have become a huge mass of people-as-objects to be moved around, confined, and profited from. The great struggle for an individual who is imprisoned is to reverse this subject/object relationship even if it is only in the mind. As the art object comes into being, its qualities speak back to the artist, suggesting the next move, presenting new possibilities. This back-and-forth process, which continues until the piece is finished, is welcome interactivity in a system designed to eliminate sharing and choice.”

Art provides not only and not necessarily “evidence” of the inhumanity, cruelty, loneliness, despair of incarceration the art shows us an image of the future too or what we can become, inside and out. Any step toward abolition requires attention to the beauty and vision of the humanity suffering inside. Humanity demands freedom and when action is caged the spirit may be quenched only to re-appear via a few colored pencils, scraps of paper, and the encouragement of those outside such as Janie Paul, her late husband, Buzz Alexander, and their community of students, staff, and volunteers.

Not only Isaiah and Jesus called for the abolition of prison. So did Lenin. When he arrived in April 1917 at the Finland Station in Petrograd the fifth thesis of his April Theseswas the abolition of police.

Bill Ayers in Demand the Impossible: A Radical Manifesto (2016), starts off quoting Che Guevara, “Be realistic, demand the impossible.” Bill Ayers demands the abolition of prison. He knows that a thousand steps of de-incarceration are required and he bravely sets out naming eighteen of them from public health to drug treatment, from homes for the homeless to a living wage, from release of prisoners over fifty years old to restorative justice. Subtract the eighteen steps he names from the thousand steps and 982 remain. Did he overlook one? Let the nineteenth be the art studio!

Sometimes de-incarceration is actually excarceration, that is, not a slow movement of a thousand steps but a single coup, a great escape, a leap, and the walls come tumbling down in insurrection, or when former African American slaves unlocked the doors of the terrifying prison at the heart of the British empire as Benjamin Bowsey and Glover did in London during the American Revolution. That’s history. Art can do the same which is to unleash the imagination and get us thinking and dreaming.

Ruth Wilson Gilmore in her book Abolition Geography shows that abolition is not only an absence. She says, paraphrasing W.E.B. DuBois in Black Reconstruction in America, it is “a fleshly and material presence of social life lived differently.” It has to do with “how to work with people to make something rather than figuring out how to erase something.” The prison is abolished when it is no longer necessary. “If unfinished liberation is the still-to-be achieved work of abolition, then at bottom what is to be abolished isn’t the past or its present ghost but rather the processes of hierarchy, dispossession, and exclusion that congeal in and as group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death.”

What are the meanings in these pictures from prison? The answer will be another back-and-forth process, this one between you and the art. They say beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and sure some of it is. For me I tend to translate aesthetic meanings into social even legal meanings. Accordingly, I came up with the following rights which art enables me to stand on.

The right to clean air (G. English, Sunset Along the Au Sable);

the right to water (Alvin Smith, The Lack Thereof, James Gostlin, Going Fishing);

the right to the countryside (Kevin Babcock, A Country Day, Bryant Ziegler, The New Homestead);

the right to the city (RIK, Suffragette City, Kenneth Ray Crable, Which Road Are You On?);

the right to play (Curtis Chase, Mending Fatherhood, David Allen Kurbaba, Game Time);

the right to a sweet (Wayne Farren, Cupcake and Everything On the Table);

the right to mail (Wynn Satterlee, Mail Day;

the right to love (Lionel Stewart, Same Sex Romance);

the right of recognition (Rafael DeJesus, Vanishing, Duke Simmons, He Sees Us);

the right of good neighborhood (Darius White, Waiting, Gerard T. Brown, Paradise, G. English, Halloween Fun Time);

the right to art (Ronald King Hood, Hood’s Gallery, Christopher Levitt, The Painter: A Portrait of Prison, Duane Montney, A Selection Visit);

the right to loving childhood (Sara Ylen, Sarayu);

the right to roam or to wander (Bryan Earle, From Under my Umbrella)

the right to explore the cosmos (David McKinney, The Scientist #3);

the right to dream (Harvey Pell, The Absinthe Traveller and Phoenix Fire);

the right to music (Kushawn Miles-El, Puritan Ave. After Hours, Father and Son Moment);

the right to co-exist with our animal relations (Arthur Harriger, Leap of Joy, Kevin Ouellette, Man’s Bests Friend);

the right to heritage (Uri Scharfenstein, Jacob’s Blessing, Alan Compo, Self-Correction);

the right to have and to hold the beauty, creation, and magic of wedding (Samantha Bachynski, Wedding Dress).

Samantha Bachynski, Wedding Dress.

These pictures ought to hang in school rooms, indoor places like hallways or stair cases, doctor’s offices, train stations, church basements, bus depots, hospital rooms, wherever people wend their weary way. We need to replace clamorous buying and selling, and relentless consumerism. We may pause to reflect upon those questions these artists have posed through their works. Memory requires work. We too must be jarred to think afresh.

Criminalization is the political process accompanying privatization. Prison-industrial complex at base of an entire way of life including the school-to-prison pipeline, housing evictions, health care. Who are prisoners? Ruth Gilmore says they are “modestly educated women and men in the prime of their lives.” “To me abolition is utopian in the sense that it’s looking forward to a world in which prisons are not necessary because not only are the political-economic motives behind incarceration gone, but also the instance in which people might harm each other are minimized because the causes for that harm (setting aside, for the moment, psychopaths) are minimized as well.”

Out-sourcing and union busting, the death penalty, detention centers, widespread administration of pacifying drugs, special housing units, and new prisons composed the conjuncture of mid-1970s during the first oil shock. In the intellectual and scholarly world of radicals and reformers it was the time of the social history of E.P. Thompson or the penological studies of Michel Foucault. It was the time too of active feminism against patriarchy and male chauvinism, also a time of gay liberation. Our voices were tin with anger because the budgets for incarceration so exceeded that for education, and at the time I hardly knew what to do about it. Here is part of the answer written by folks for whom angry scarlet was not the only color on the palette, but which affected them all just as red blood cells carry the air we breathe and give us life.

The Michigan prison artists are not propagandists; they are not producing for a movement which as of yet scarcely touches them, even though the great abolitionists of our time such as Angela Davis, these artists are doing something else. Janet Zandy writes “Art is not something to be plucked by those with the most power. Art is integral to human existence. Human beings are drawn to visual expression as they are drawn to story telling. When that longing for beauty is thwarted or denied, ridiculed or demeaned humans suffer.”

History, religion, art tell us prisons are no good. They and the system perpetuating them must go.

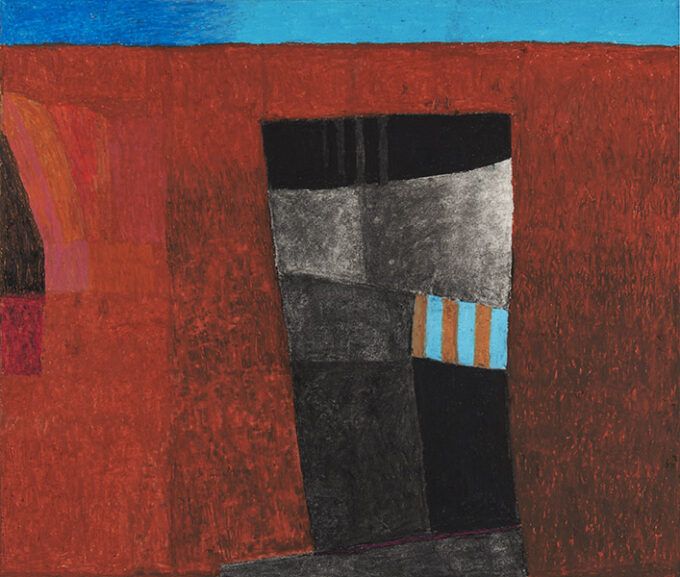

Janie Paul, Still Here.

The book concludes not with her last word but an image of Janie Paul’s own. Still Here it is called. In monumental simplicity it shows a mammoth dark gray rectangle off-center with an unsteady grounding against a rusty, earthy background. Within this bleak house bronze bars divide the sky of cerulean blue. That black rectangle is off balance, and a thin line of blood, like the mortar said to fix the stone buildings of European slave ports, separates what seems like the ominous penitentiary from a triangular foundation. We anticipate a slide, perhaps abolition. But hold it, what is that slight black form on the painting’s edge if not the possibility of another penitentiary? Careful, we are not home yet. Getting there will partly depend on the visions and wisdom held in this book, the result of the author’s twenty-eight years visiting Michigan prisons and talking to the artists confined therein. A community was formed that bridges the walls, that affirms the artists, and that expresses our need not to be separated.

References and Further Reading

Bill Ayers, Demand the Impossible: A Radical Manifesto (Chicago: Haymarket, 2016)

Jimmy Santiago Baca, A Place to Stand (Grove Press, 2001)

Jordan T. Camp, Incarcerating the Crisis: Freedom Struggles and the Rise of the Neoliberal State (Oakland: University of California Press, 2016)

Angela Davis, Are Prisons Obsolete? (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2003)

Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, translated by Myra Bergman Ramos (New York, 1970)

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Abolition Geography: Essays Towards Liberation (New York: Verso, 2022)

Karl Marx, The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844, translated by Martin Milligan (New York: International Publishers, 1964)

Raoul Peck, Exterminate All the Brutes (2021)

Henry David Thoreau, Walden; Or, Life in the Woods (1854)

Janet Zandy, What We Hold in Common (2001)

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home