From ‘Genghis Khan with rockets’ to a ‘gas station with nukes’: How the EU’s top diplomat updated a lazy Russophobic slur

Josep Borrell used a modern variation of a jaded trope to abuse Russians: here’s where the lazy stereotype comes from

An insult defining the USSR as “Upper Volta with missiles” has been widely used since the 1980s. It has now morphed into the idea that Moscow runs a “gas station with nuclear weapons,” which appears to have its origins in comments from the late US Senator John McCain, who rarely, if ever, saw a Western-backed war he didn’t like.

In the 21st century, the origin of this type of phrase has been repeatedly debated. It will be shown below that it goes back to statements from the 19th century thinker Alexander Herzen and has more than a century and a half of history behind it.

Here are four successive variations of the metaphor:

- Genghis Khan with the telegraph and Congreve rockets

- Genghis Khan with the atomic bomb

- Congo with missiles

- Upper Volta with missiles

In all these formulas, the first part symbolises some force seen as uncivilised, and alien to Western values, and the second part symbolises the achievements of Western civilisation, primarily in the military field.

Genghis Khan with the telegraph

In early 1857, the librarian Baron Modest Korf’s book about Nicholas I’s accession to the throne was published in St. Petersburg. It was written at the behest of the monarch and published for the general public on an order from Alexander II. The purpose of the publication was to belittle the achievements of the Decembrists (unsuccessful revolutionaries in the 1820s) and discredit their motives.

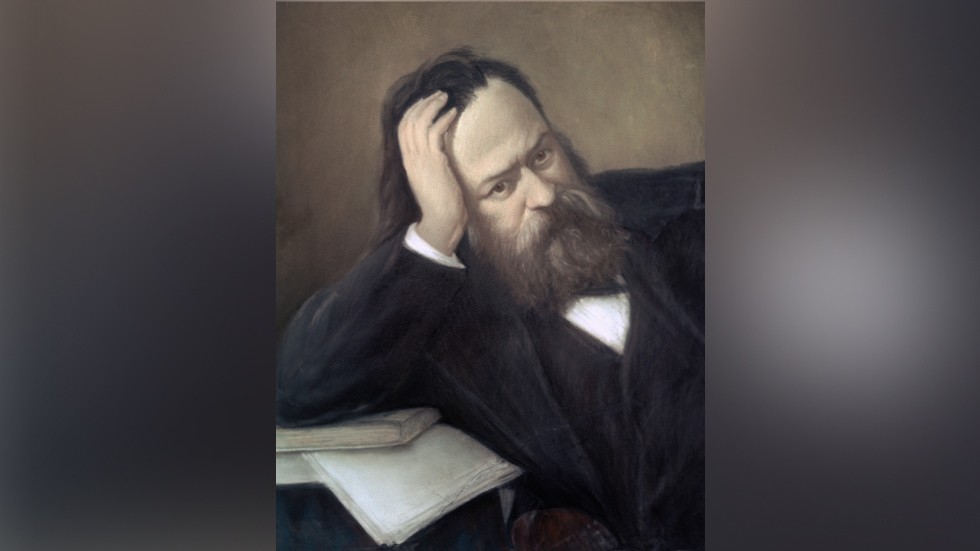

In October 1857, an open letter from Herzen to Alexander II about Korf's book appeared. In order to prove the historical justification of the Decembrist movement, Herzen essentially challenged the poet Alexander Pushkin’s (then unknown) formula: “The government is the only European in Russia.” He wrote: “If we had made all our progress only in government, we should have given the world an unprecedented example of autocracy, armed with all that freedom has developed; slavery and violence, supported by all that science has found. It would be like Genghis Khan with telegraphs, steamships, railways, with Carnot and Monge at headquarters, with Minier guns and Congreve rockets under Batu's command.”

The “Congreve rocket” – a gunpowder projectile with a range of up to three kilometres – was invented by the British general William Congreve and laid the foundation for European rocketry. They were successfully used by the British army in the Napoleonic Wars: in the bombardment of Boulogne (1806), Copenhagen (1807) – the city was burned to the ground – and in the Battle of Leipzig (1813). However, from the second half of the 19th century, rockets lost their role as an important military weapon – for a century.

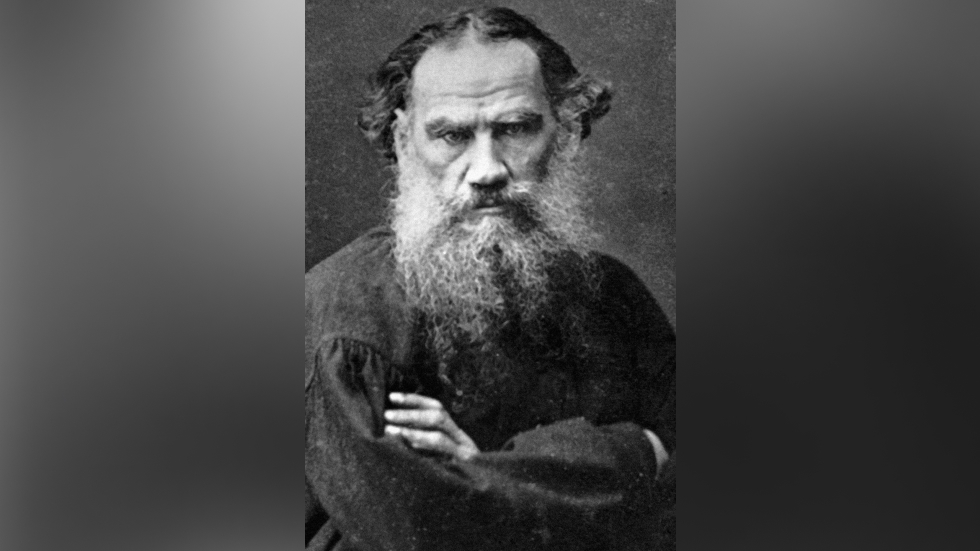

The metaphor of “Genghis Khan with the telegraphs” entered the public consciousness much later, at the end of the 19th century, and the great writer Leo Tolstoy played a decisive role in this. On 31 July 1890, he wrote to the lawyer and philosopher Boris Chicherin: “It was not without reason that Herzen spoke of how terrible Genghis Khan would have been with telegraphs, with railways, with journalism. This is exactly what has happened in our country.”

Tolstoy developed this idea in “The Kingdom of God Within You” (Paris, 1893; in Russian: Berlin, 1894): “Governments in our time – all governments, the most despotic as well as the most liberal – have become what Herzen so aptly called Genghis Khan with telegraphs, i.e. organisations of violence, having nothing as their basis but the most crude arbitrariness, and at the same time using all those means which science has developed for the aggregate social peaceful activity of free and equal people, and which they use for the enslavement and oppression of people.”

“Genghis Khan with the telegraph” is one of the working titles of Tolstoy's article “It is Time to Understand” (published in 1910). “The Russian Government,” it says, “is now the very Genghis Khan with the telegraph, the possibility of which so terrified him [Herzen]. And Genghis Khan not only with the telegraph, but with a constitution, with two chambers, a press, political parties et tout le tremblement… The difference between Genghis Khan with the telegraph and the old one will be only that the new Genghis Khan will be even more powerful than the old one.” The article was translated into the main European languages and, together with the treatise “The Kingdom of God Within You,” introduced Herzen’s metaphor to Western readers.

Thus, Tolstoy’s “Genghis Khan with the telegraph” is a definition not only of the Russian government, but of the modern state in general. In the revolutionary press, and then in the post-revolutionary Soviet press, this metaphor was usually applied to autocratic Russia. The extent to which it was associated with Tolstoy is illustrated by a remark by the eminent historian Mikhail Pokrovsky: “Leo Tolstoy called this [tsarist] state ‘Genghis Khan with the telegraph’.”

In the post-revolutionary emigré press, Herzen's words were applied to Bolshevik Russia. However, the ideologist of National Bolshevism, Nikolay Ustryalov, makes an important qualification: “It cannot be said that the old culture collapsed at once and completely. Nor can it be said that the new element – this ‘chauffeur’ or ‘Genghis Khan with the telegraph’ – is something absolutely primitive and homogeneous.”

In 1941, the same metaphor was applied in the Soviet press to the Nazi state: “Herzen once speculated with horror about the possible appearance of ‘Genghis Khan with the telegraph,’ about the coming barbarians equipped with advanced technology. But no one, not even the darkest imagination of the advanced people of the 19th century, could imagine what would happen in the 20th century, when fascist thugs began to realize their plans for the enslavement of mankind and the eradication of its culture”.

Genghis Khan with an atomic bomb

After the Second World War, the émigré philosopher Semyon Frank modernised the metaphor in its technical part, including the atomic bomb: “One hundred years ago, the astute Russian thinker Alexander Herzen predicted the invasion of ‘Genghis Khan with the telegraph’. This paradoxical prediction has come true on a scale that Herzen could not have foreseen. The new Genghis Khan, born from the bowels of Europe itself, has descended upon it with aerial bombardments destroying entire cities, gas chambers for the mass extermination of people, and now threatens to sweep mankind off the face of the earth with atomic bombs.” Frank uses the metaphor in the spirit of Tolstoy – as a universal characteristic of the modern state, free from the norms of human morality.

Five years later, the émigré Socialist Herald published an article by publicist Pavel Berlin entitled “Genghis Khan with a hydrogen bomb.” The author traced the historical lineage of Russian communism back to the era of Tatar-Mongol rule, without stopping to assert that “Genghis Khan introduced a communism that went further than the Soviet one… Both systems were built on the complete detachment of the successful mastery of the latest technology, including, first and foremost, the technology of extermination, from the cultural soil that gave birth to it and developed it.”

“Leo Tolstoy,” writes Berlin, sharing a common misconception at the time, “put into circulation the expression ‘Genghis Khan with the telegraph’... reality brought us in the person of [Joseph] Stalin. Genghis Khan no longer with a peaceful and innocent telegraph, but with an all-destroying atomic bomb.” Now “we see… [Prime Minister Georgy] Malenkov with a hydrogen bomb.”

That same year, the July issue of the conservative magazine The American Mercury published an article by J. Anthony Marcus entitled “Will Malenkov Succeed?” The author wrote: “I recall those years when the manufacturing industry was extremely poor. Russia did not have a single tractor, tank, submarine, bomber or fighter of its own manufacture, let alone modern means of producing and distributing food and clothing and other necessities.”

“This is not the Russia that Malenkov inherited. Today he is Genghis Khan with atomic-hydrogen bombs, determined to use them to establish world domination – a course from which neither he nor his successor will ever be able to deviate for long.”

The similarity of this passage with the corresponding fragment of Berlin's article is obvious. Marcus, a staunch anti-Communist, was born in Russia, knew Russian well, had visited the USSR many times before the war on Amtorg business, and had the closest ties with the Russian political emigrants in America. Later one of the emigrant authors attributed this formula to Leon Trotsky: “Trotsky overestimated Stalin, calling him Genghis Khan with an atomic bomb”. Of course, Trotsky, who was assassinated in 1940, could not have said any such thing.

From the late 1960s, Herzen's metaphor was applied in the Soviet press to the USSR's Western adversaries: “Genghis Khan, armed with a hydrogen bomb and rockets, is no longer a fantasy, no longer a novelist's fiction, but a reality that must be reckoned with, lest one day we find ourselves in the position of humanity being forced to recognise the advantages of salamanders.”

In a 1971 article on the arms race in space, Herzen's warnings were redirected in accordance with the needs of Soviet propaganda: “Herzen was tormented by the thought of the fate of humanity and the fate of science, which had fallen into the power of lovers of colonial robbery and military adventures. It would be, wrote Herzen, ‘something like Genghis Khan with telegraphs, steamships, railways, with Minier guns, with Congreve rockets under Batu's command’.”

“Genghis Khan with telegraphs! Yes, then, in the middle of the XIX century, telegraph wire and Congreve rockets flying at two hundred fathoms were the ceiling of technical power, and the Russian Tsar and the French Emperor were the embodiment of tyranny and the trampling of human rights. Today it all seems like child's play. Rockets fly nowadays to Venus and Mars, and modern Genghis Khans own not only telegraphs, but also television installations, lasers, computers and many other things. The Genghis Khans of our days are also swinging into space.”

Another Soviet author applies the metaphor to Maoist China: “Herzen saw this danger in the image of Genghis Khan with a telegraph. Leo Tolstoy wrote of Genghis Khan with a parliament. We now know that Genghis Khan with the atomic bomb and even Genghis Khan with a revolution, like Mao Zedong's 'cultural revolution', are also possible.”

Such comparisons were also made in the Western press, facilitated by the fact that Genghis Khan had long been synonymous with the 'yellow peril'. In 1968, a book by an American author on Yugoslavia quoted (without source) a “remarkable prophecy” by US Supreme Court Justice William Douglas (1898-1980), which the author of the book dated to 1955[19]. He was referring to the threat from Communist China: “The Russia of the next generation may indeed soften to the level of today's Communist Yugoslavia. If Asia industrialises and produces a Genghis Khan with a hydrogen bomb, Russia and America may become indispensable to each other if both are to survive.”

Congo with thermonuclear missiles

After the creation of ballistic missiles with nuclear warheads, the mention of "Congreve rockets" gained unexpected relevance. As shown above, the theme of “Genghis Khan with missiles” emerges in the Soviet press as early as in the 1960s. The next transformation of the metaphor took place in France: instead of the name of Genghis Khan as a symbol of barbarism, the name of an African country appears.

In 1973, the book ‘What I Know about Solzhenitsyn’ was published in Paris. Its author, the art historian Pierre De (1922-2014), a member of the French Communist Party (CPF) since 1939, had written laudatory books about the Soviet Union in the 1940s and 1950s. In 1968, however, he greeted the Prague Spring with enthusiasm. In his new book, De recalled conversations with the writer Elsa Triole in 1968 (Elsa was then writing an article about Academician Andrey Sakharov's manifesto Reflections on Progress, Peaceful Coexistence and Intellectual Freedom):

“I had just published an article about the long time span of history, about profound movements on the scale of whole centuries, imperceptible to traditional analyses. She replied: There is a long Russian time, Pierre. And I would like to know where it leads... It was you who told me that Courtade, shortly before his death … told you that this country is the Congo with thermonuclear rockets (le Congo avec des fusées thermonucléaires).”

The credibility of this report remains questionable: Pierre Courtade, a member of the CPF Central Committee since 1954, as far as is known, remained an orthodox communist and apologist for the USSR until the end of his life.

The appearance of Congo in this formula is hardly accidental: in the 1970s, the Congo had a military dictatorship trying to build socialism on the Soviet model. In September 1973, the formula “Russia is the Congo with rockets” appeared in the headline of the German newspaper Die Zeit. The author of the article, François Bondy, cited the book by Pierre De. A year later, Bondy linked this formula to Herzen's metaphor.

Bondy, a Swiss journalist, writer and translator (including from Polish), a close friend of Romain Gary, a French writer of Russian origin, was, it must be assumed, well acquainted with Russian literature. Speaking to US state-run CIA mouthpiece Radio Free Europe about the prospects for détente, he said:

“You could say that by accelerating the process of complicating the system in Russia, you are accelerating its decline, because highly qualified Russians (allegedly) will not tolerate totalitarianism. I am not at all convinced. The simple and sobering fact is that our relations with Russia are different from those with any other country, and this is due to the historical, cultural and political ‘otherness’ of the Soviet Union. Pierre Courtade, former editor of the French Communist newspaper L'Humanité, described the Soviet Union after a recent trip there as ‘Congo with rockets’, echoing Alexander Herzen's fears of ‘Genghis Khan with the telegraph’. The truth is that we have no answer to this question. The best we can hope for is to encourage the keepers of the missiles to keep their missiles at a distance and to pay more attention to any move that this system might make to break out of its Congo.”

In the printed English version of the radio broadcast, the French term “des fusées” is rendered by the word “rockets.” However, the French "fusée" and the Russian “rocket” correspond to two terms in English – “rocket” and “missile.” The first usually means a space rocket, the second a military guided missile, including one with a nuclear warhead. The fact that the form “...with rockets,” which is still common today, appeared first is probably due to the genealogy of the expression, which goes back to the Russian-language metaphor. Since the 1990s, the form “Upper Volta with missiles” has also been used.

Upper Volta with missiles

The replacement of Congo with Upper Volta, a small and impoverished African country almost invisible on the world map, emphasized the paradoxical nature of the metaphor. The first known reference to “Upper Volta with missiles” dates from the autumn of 1983. It is important to note that one of the central issues in the press at the time was the conflict over a South Korean civilian Boeing shot down by a Soviet air-to-air missile off Sakhalin Island on 1 September 1983.

On 28 October 1983, the left-wing British weekly New Statesman reviewed two new books on the USSR, including Andrew Cockburn's The Threat: Inside the Soviet Military Machin. Cockburn, the Irish-raised son of the British communist Claude Cockburn, has lived in the United States since 1979. The main thesis of his book is that Western politicians exaggerate the power of the Soviet war machine to justify their own arms programs. Soviet technology is decades behind Western technology. At parades, the missile forces (to quote a reviewer of the book) “display carefully lathed wooden missiles; the units marching on Red Square never learn how to fight; the new jets can stay in the air for only a few minutes.”

According to the reviewer, much of the book is true, but Cockburn is not free of the biases characteristic of the New Cold War, namely “anti-Russian racism, which tends to portray the Soviet Union as both weak and barbaric. Every counterrevolutionary, from Sidney Reilly to General John Hackett, has used this motive to incite hatred and aggression against the USSR. Those who accidentally shoot down Korean airliners are outside civilization. Those who bomb mental institutions in Grenada are simply ill-informed. The Russians are portrayed with a racist tinge: a bunch of dirty men pretending to be a great power – ‘Upper Volta with missiles’, as diplomats in Moscow joke.” Later evidence confirms that the expression originated in Moscow among foreign diplomats (and probably journalists).

A little earlier, in the spring of 1983, Ronald Reagan had described the USSR as an “evil empire.” This definition contrasts stylistically with the definition of “Upper Volta with missiles.” If the “evil empire” image demonized the USSR, the “Upper Volta with missiles” image challenged the notion of the USSR as a superpower.

A year later (1984), the Republic of the Upper Volta was renamed the Republic of Burkina Faso, but this name did not replace “Upper Volta” in our metaphor.

According to one popular version, the phrase “Upper Volta with rockets” was coined by the British journalist David Buchan. He was referring to his article “Moscow can do it too: Soviet technology exports,” published in the Financial Times in September 1984.

It was widely circulated during the years of perestroika. The Irish journalist Patrick Cockburn recalled: “'Upper Volta with missiles', a journalist said to me in my first days in Moscow. A week later, at dinner, a diplomat repeated the remark. Over the next three years, I heard the same annoying joke repeated many times, with mockery and contempt.”

Since the late 1980s, the phrase "Upper Volta with missiles" has been quoted in the German press, usually in reference to Helmut Schmidt (Federal Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany 1974-1982). The German version is "Obervolta mit Raketen" and also "Obervolta mit Atomwaffen" ("Upper Volta with atomic weapons").

In the Russian press of the 2000s, the same metaphor was often attributed to Margaret Thatcher. In 1999, British journalist Xan Smiley published a letter on the pages of the online resource POGO. Centre for Defence Information: “Henry Kissinger, Helmut Schmidt and even Mikhail Gorbachev have been cited as authors of this phrase. I'm sorry, but it was I who first put it into circulation. I think it was in the summer of 1987, when I was a correspondent for The Daily Telegraph (London) and The Sunday Telegraph in Moscow (1986-1989). At the time, the phrase was a source of amusing insults, and I was denounced in the Soviet press for being ‘rabidly anti-Soviet’ and the like.”

“In fact, I had previously heard the idea expressed in a similar way by a woman (not a journalist) who happened to be Zimbabwean, and I probably twisted the expression. Unfortunately, the people of Upper Volta have long referred to their country as Burkina Faso. Poor Upper Volta, though... it sounded both more hopeless and more amusing. In any case, it is not clear to me why the credit should go to the aforementioned bigwigs (if it is any credit at all).”

As shown above, Smiley was deluded in attributing credit to himself.

The Washington Post on 8 February 1991 quoted Russian politician Viktor Alksnis as saying, “The West used to think of the Soviet Union as Upper Volta with missiles. Today, we are considered just an Upper Volta. Nobody is afraid of us.” On 25 January 1992, Boris Yeltsin said in an interview with ABC television that Russian nuclear missiles would no longer be aimed at American cities as of 27 January. Komsomolskaya Pravda columnist Maxim Chikin noted in an article on 30 January: “The task is simple. Upper Volta with missiles minus missiles. What is left? Exactly.”

Let us also note an example of the use of Herzen's metaphor (in Leo Tolstoy's version) in the 2000s: “As the angry but not entirely witty revolutionary Herzen once put it, ‘Genghis Khan with a telegraph is even worse than Genghis Khan without a telegraph'. George Bush Jr. is precisely 'Genghis Khan with a telegraph’.”

The endurance of this metaphor, created more than a century and a half ago, is proof of the existence of the “long time span" of Russian history, to use French historian Fernand Braudel's term.

This piece was originally published by Russia in Global Affairs, translated and edited by the RT team

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home