Why Do People Want to be Nazis?

Image by Chris Boese.

What compels someone to become a Nazi? Furthermore, what compels someone to remain one after the regime the party installed is decimated and forced to surrender? An ancillary question is why do the concepts that inform Nazism continue to have genuine adherents in the world of today? Although there are no definite answers to these questions, a couple recent novels provide us with scenarios that somewhat explain why they continue to be asked. Inspired by two very different lives, the texts describe a world that is both quite unfamiliar yet frighteningly recognizable. The fact that it is these fictions that give us insights into the Nazi mindset—insights perhaps more fundamental than any sociological or psychological study might—makes a statement about modernism and humanity’s various reactions to it.

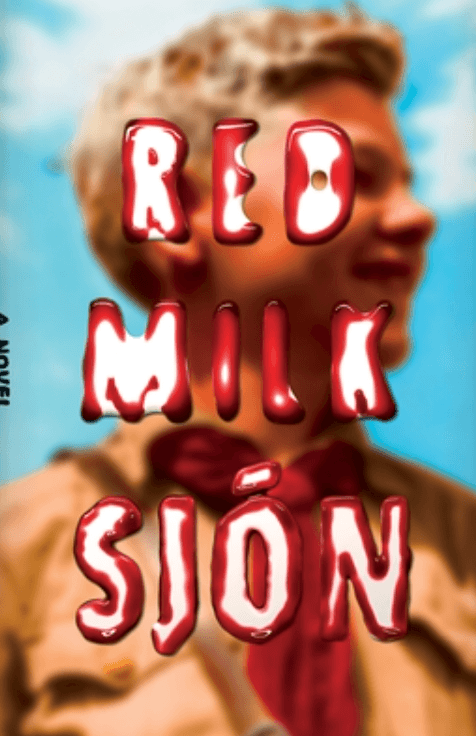

Red Milk, by Sjón, is an Icelandic novel wonderfully translated by Victoria Cribb. In relatively few pages, the story of the leader of a small group of neo-nazis Gunnar Kampen is relayed. The fictional group of Nazis he is part of is based on an actual group in Reykjavik that existed during the 1950s and 1960s. The real party was known to perhaps a few thousand Icelanders at most during its heyday. The novel describes the protagonist Kampen’s philosophical journey from a household that was anti-fascist during World War Two to becoming the leader of his Nazi organization. The narrative takes the form of letters, propaganda pamphlets and straight narrative with a singular point of view. Kampen’s political efforts result in a trip to Britain where he is scheduled to meet with other neo-nazis interested in forming an international presence. The newsletter he publishes together with an exchange of letters has brought him to this point.

Sparse in its description of Kampen’s personal life and the postwar society he came of age in, the novel in its telling creates an awareness in the reader of his emotional and mental state. Extraordinarily ordinary except for his Nazism, one lesson of the novel is the ordinariness of those who become enchanted with the potential and appeal Nazism offers to certain individuals. As we know, that potential can propel those who have succumbed to the appeal to incredibly destructive and deadly acts. In the novel Red Milk, however, the only certain death is that of Gunnar Kampen. Indeed, the novel’s opening chapter is a brief description of the immediate aftermath of his passing. Two policeman examine his person after Kampen is found murdered on a train in Cheltenham Spa on the edge of the Cotswolds in the county of Gloucestershire, England.

Coincidentally, the protagonist of the second novel reviewed here finds his death at the sea, also. This man, one of the world’s most well-known Nazis, is Josef Mengele. The Auschwitz doctor and long-time fugitive from justice or revenge, it is supposed he died in the ocean near Bertioga, Brazil. His corpse was positively identified through DNA analysis almost six years after his death; the family and a couple remaining friends had quietly buried him on a farm in Brazil and said nothing. Like much of the rest of his life, Josef Mengele’s death was a secret to all but a very few. In his new novel, The Disappearance of Josef Mengele, author Olivier Guez tells a version of the Nazi doctor’s life as a fugitive. I might add, a life that was too good for him.

Mengele, whose infamous experiments on human captives in the concentration camps constructed and managed by the Third Reich, escaped from the calamity and destruction that World War Two made of much of Europe. Like others in the Nazi bureaucracies and military, he ended up in South America. The pursuit of these international criminals by officials from the United States and other governments on the winning side of the war was intense at first. As time passed and other things like reconstruction took precedence, the hunt became the task of the newly formed nation-state of Israel. For obvious reasons, its agents in the intelligence agency Mossad took the hunt personally. Likewise, they also took it to extremes. Meanwhile, other nazi functionaries were granted reprieves and went to work for agencies in Washington, Bonn and other cities of the so-called free world. Washington had manipulated its way to the forefront of this world and had made it clear that it considered the biggest threat to its economic hegemony was the former ally headquartered in the Kremlin.

Guez’s novel is well-conceived and well-told. The translation seems impeccable. Although based on well-researched information, the narrative reads like a novel. Emotions reveal themselves in a natural way—although Mengele himself seems relatively bereft of them. It is some of his family members and friends that shed tears or express fear for his life. One assumes it was this calculating manner that enabled him to pursue his twisted science in Auschwitz; science which was often nothing but straight out torture. From the young adherents to the Nazi faith to his leftist nephew with whom he used to enjoy childhood moments with; the reader meets individuals somehow connected to this man, this patron of the devil. There are also friends and even lovers; their relationship acknowledges his humanity.

Perhaps that is the point of these novels—to acknowledge the fact that these men are human. Their beginnings are not that unusual, not really. Their paths through life are fairly conventional. Mengele went through university and medical school; Kampen works at a bank. One ironic if not humorous moment in Red Milk involves Kampen being called into the bank manager’s office because of his growing political outspokenness. Kampen realizes the office is the vantage point of a photo of a Nazi rally from the occupation. He also realizes the manager who is now disapproving of his views was one of the people in the photograph he is recalling. However, their particular fascination with the political movement called Nazism sets them apart. Or, does it? Perhaps that question too is the point of these novels.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home