Iran and the US: When friends falls out

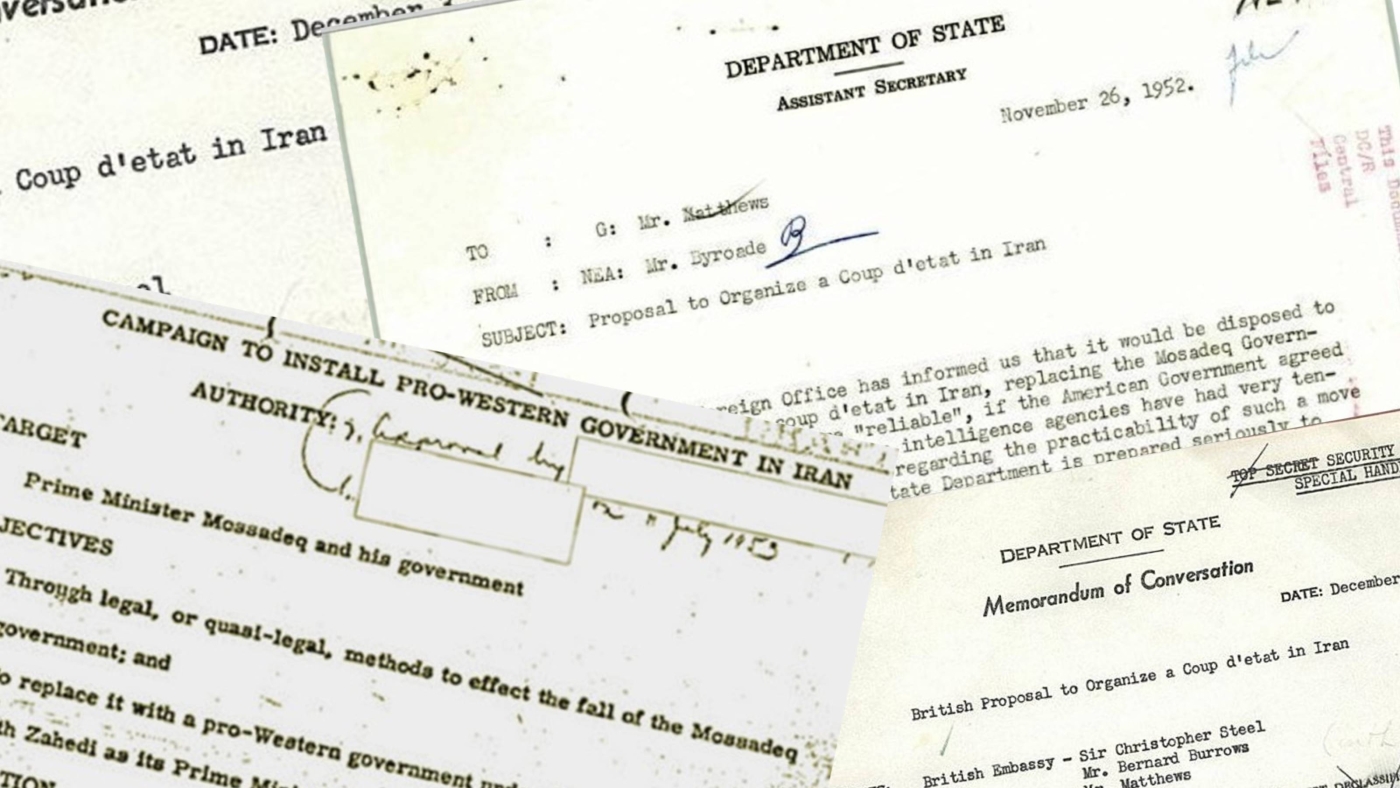

In 1953, a CIA coup powered by fake news deposed the government of Iran in the service of US and British geopolitical interests. Its resonance is still felt today

Under the glittering chandeliers and gilt-panelled walls of a Hapsburg palace in Vienna, Iranian and American negotiators are right now locked in conflict talks. At stake is the revival of the historic 2015 nuclear deal, which sought to resolve a key element in more than 40 years of US-Iran enmity and which Donald Trump, then the US president, abruptly withdrew from in 2018.

Trump set the United States once again on a path to regime change in Tehran, and plunged the Iranian economy, poised to reap the benefits of the agreement, into free fall. Looming over the talks is the prospect of what failure might hold: a potential US or Israeli strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities that could unleash a wave of violent retaliation across the Middle East by Iran and its allies.

Both sides in Vienna complain bitterly about a lack of trust in the other. There is no precedent in the 20th century of two countries growing so intimately close, breaking up so furiously, and then nursing their betrayal for decades to come.

The origins of both sides’ deep wounds lie in this story. Then, like today, a grand geopolitical standoff between the West and Russia loomed over Iran’s fate. In the 1950s, fake news was the expertise of the Americans and the British, who deployed it in the first successful CIA overthrow of another government, setting the template for many more to come.

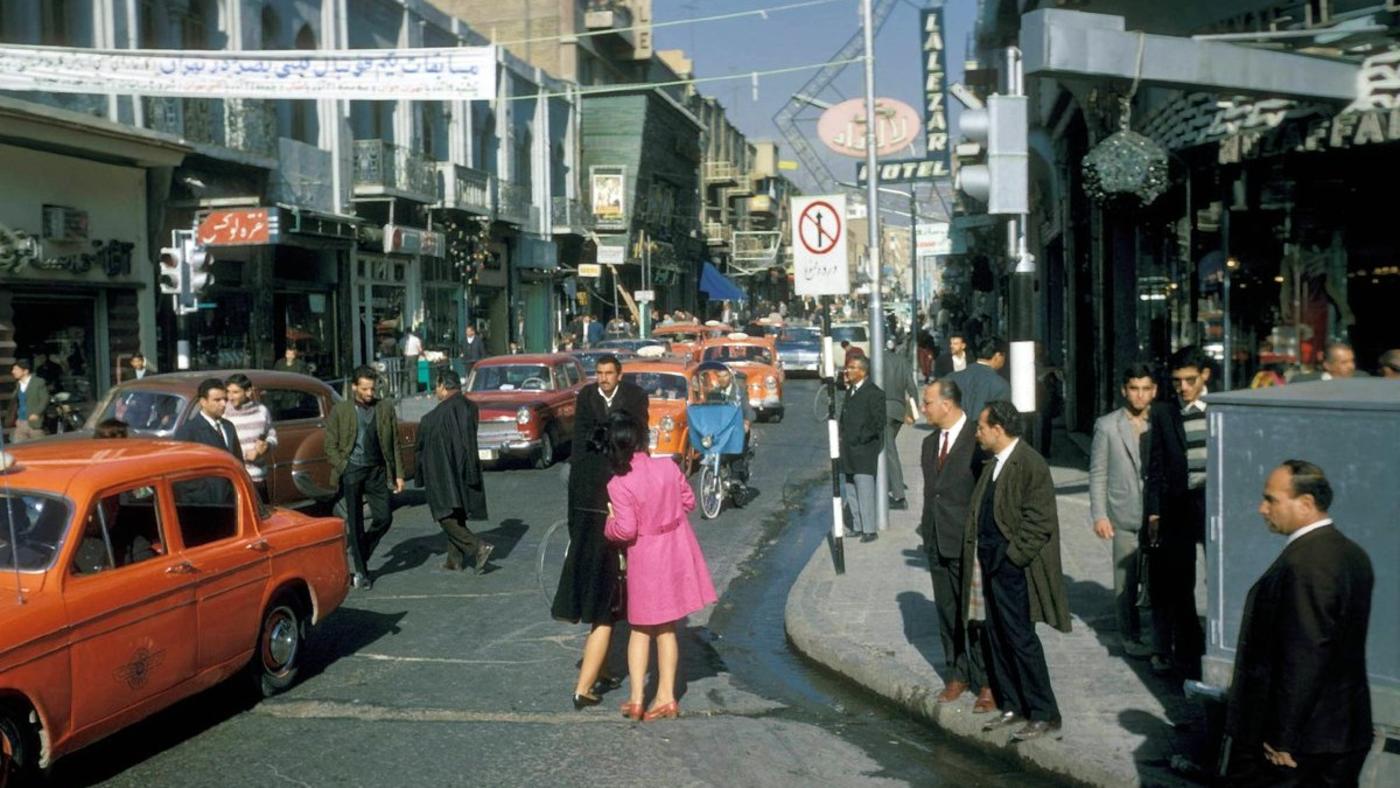

Tehran, August 1953: Oil and the West

The city is febrile. The dry heat rises up from the pavement, daily newspaper headlines scream abuse at the government, parliament is shut down and hired mobs of tattooed street hooligans gather around the streets chanting, “Long live the shah”.

Outwardly, the red brick US Embassy compound on Throne of Jamshid Street appears detached from the turmoil. Young embassy staff come and go through the gates as usual, hold barbecues by the chancery pool and play doubles tennis on clay courts.

Covertly, CIA and MI6 field agents roam the city: they buy off editors and plant fake stories in influential papers. They bribe parliamentarians and high-ranking military officers. And from a safehouse in the city’s poplar-lined cabaret district, they set in motion a coup to overthrow Iran’s democratically-elected government.

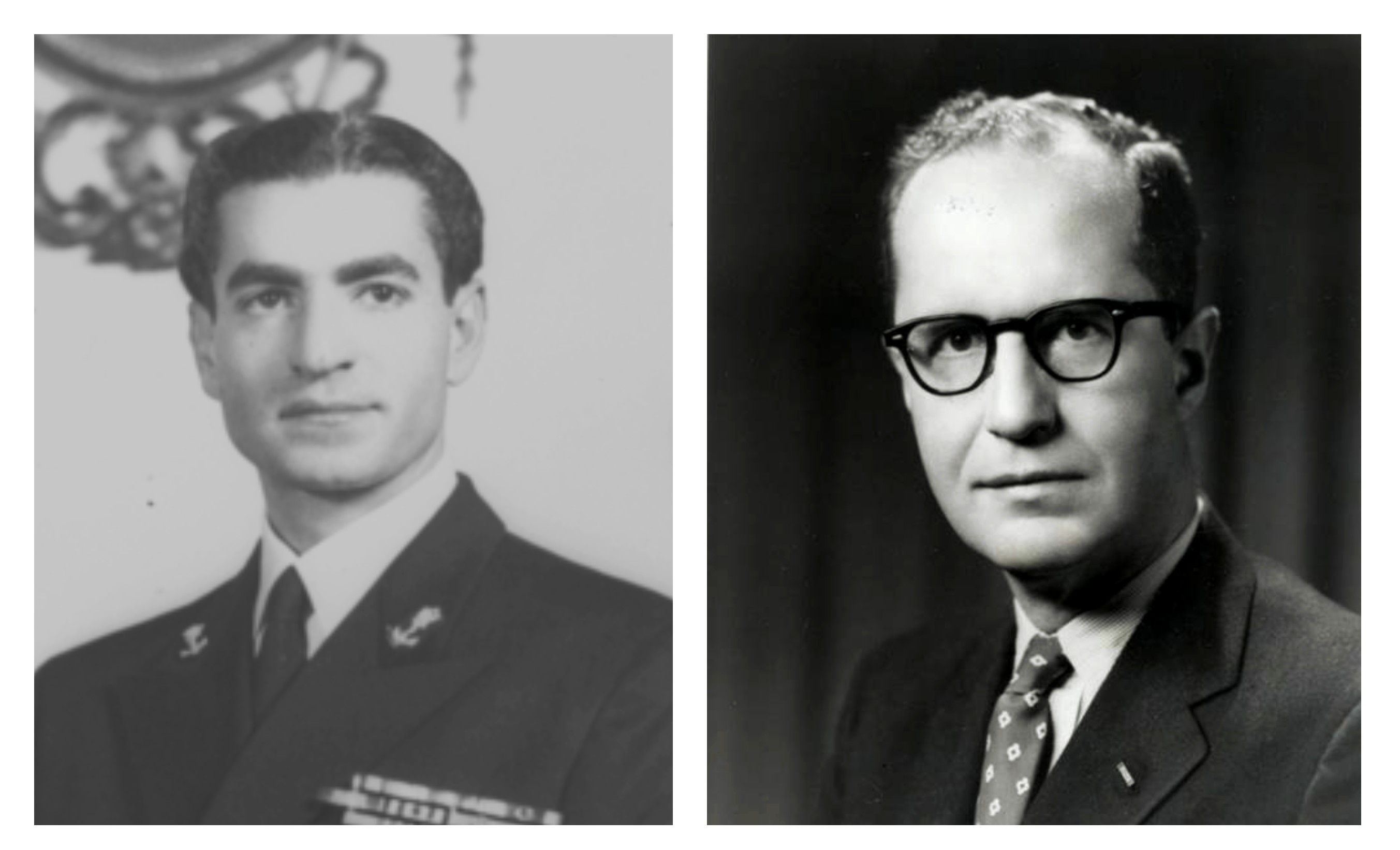

A Chevy Chrysler, its interior darkened, is parked in the grounds of Saadabad Palace, home to Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Iran’s monarch. Inside sits the CIA’s man in Tehran, Kermit Roosevelt, known as Kim to his friends. With him is the shah. Roosevelt makes a direct opening salvo.

“I’m here directly on behalf of US President Eisenhower and British Prime Minister Churchill.”

He promises both leaders will give the shah public signs of their support for the coup; Eisenhower through a pre-arranged phrase in a speech; Churchill through an altered phrase on the BBC World Service. In the dark of the sedan, they talk through the cash and allies needed for their plan, and precautions in case things go awry.

The shah asks about the oil concession, which would allow Iran to take a meagre cut of its own oil sales from the British company running the show. The British would come to generous terms with Iran, Roosevelt assures him.

Roosevelt steers the conversation, searching for a tone both threatening and sycophantic. He fails to call the shah “HIM” - short for His Imperial Majesty. The shah, his thick brows furrowed, broods silently.

Roosevelt makes clear that if he refuses to cooperate with the coup plans, the US will proceed on its own. Then, searching for a ceremonial note, he invents a message from Eisenhower about his hopes that they can solve Iran’s oil nationalisation crisis. “If the Pahlavis and the Roosevelts working together cannot solve this little problem, then there is no hope anywhere. I have complete faith you will get this done!”

Sure enough, the shah agrees to sign the decree to remove Iran’s prime minister Mohammad Mosaddegh, along with another decree appointing a new prime minister, which will mean the overthrow of the democratically elected government. The shah, by nature thin-skinned and cautious, had wanted a clear outline of the plan and firm commitments from his allies. As he climbs out of the sedan, irritated by Roosevelt’s nonchalance, he murmurs a warning: “Mr Roosevelt, you are welcome in my country, but this conversation never happened.” He then disappears into the rolling lawn of his palace.

Across town, returning home from a dinner party, Hossein Fatemi, Iran’s young foreign minister, elegantly dressed in a three-piece suit, knows trouble is brewing. Surveillance cars line the drive outside his house. The phone line is dead. He tries to keep calm as he goes about changing for bed. The anti-government protestors have been growing more militant all week.

At first, they were led by a barrel-chested goon called Shaban the Brainless, whose rent-a-crowd network was often hired by royalist politicians. But in recent days they have been joined by bearded Islamists, a growing crush of opposition to the government. Fatemi isn’t sure when his enemies will make a move against him.

Shortly after the pips on the BBC World Service signal midnight, Fatemi hears his wife Parivash screaming downstairs. He tears out of the bathroom in his dressing gown. Navy-suited Imperial Guards, guns drawn, are scaling the staircase. One shouts coarsely at Parivash to shut-up. Another grabs Fatemi by the lapels of his gown, and throws him against the bannister. “Are you armed?” the soldier asks, cuffing his hands. “Me?” Fatemi snorts. “I’ve never even held a gun in my life.”

The soldiers keep pouring into his house. They drag him down the stairs, past his sobbing wife, who clutches their baby, and throw him in the back of a military truck. Trying to stay calm, Fatemi calculates they are heading south, toward the palace. He thinks of all the previous times the king has jailed him for his editorials in Bakhtar-e Emruz back when he was just a journalist, not yet a minister. Was it six or seven?

Blood pours from his gashed brow, and he grasps the side of the truck to stop the dizziness. He hopes his comrade Mosaddegh is safe. He hasn’t spoken to the prime minister all night, wary of his tapped phone. The truck comes to a stop near the dark palace lawn, and a soldier drags him into the barracks, hurling him into a basement cell.

“See you at dawn for your execution,” another drawls, leaving him in darkness with a clang of the door. The foreign minister, his head ringing with pain, plants his hands against the wall and roars: “Even if I’m cut to pieces, the people won’t let your British lackey rule. You slaves!”

Fatemi: Young minister takes back control

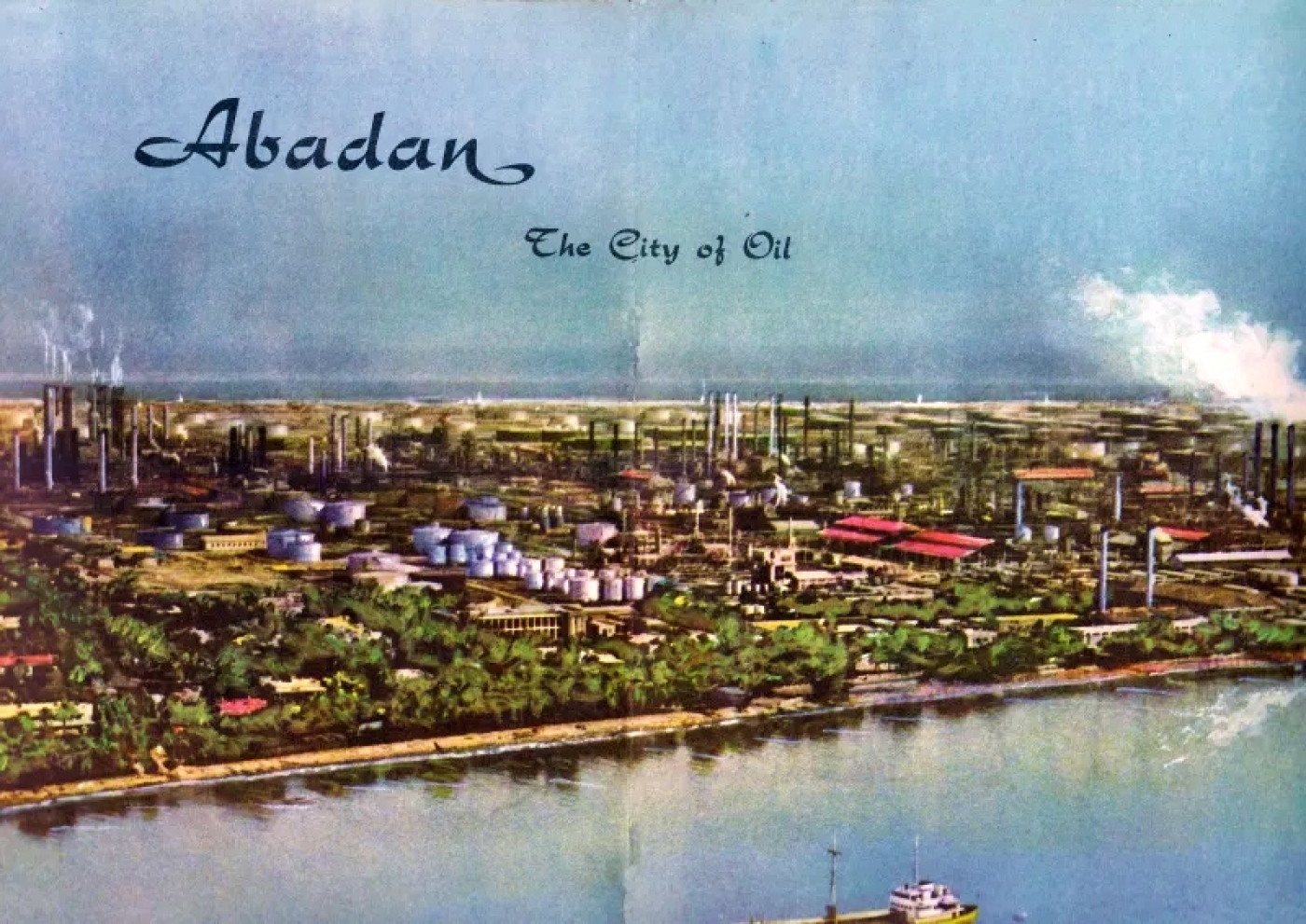

In March 1951, the Iranian oil nationalisation crisis, the most serious political and economic shock to the West in the wake of the second World War, had begun.

It was the era of revolt in the Third World, as it was called then. A wave of direct and semi-direct colonies declared their independence from old colonial powers. The British never formally governed Iran, although they did occupy it during much of the 1940s. And the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, a British firm, had been tapping, extracting, and drawing nearly all the profits from the country’s vast oil reserves since 1909.

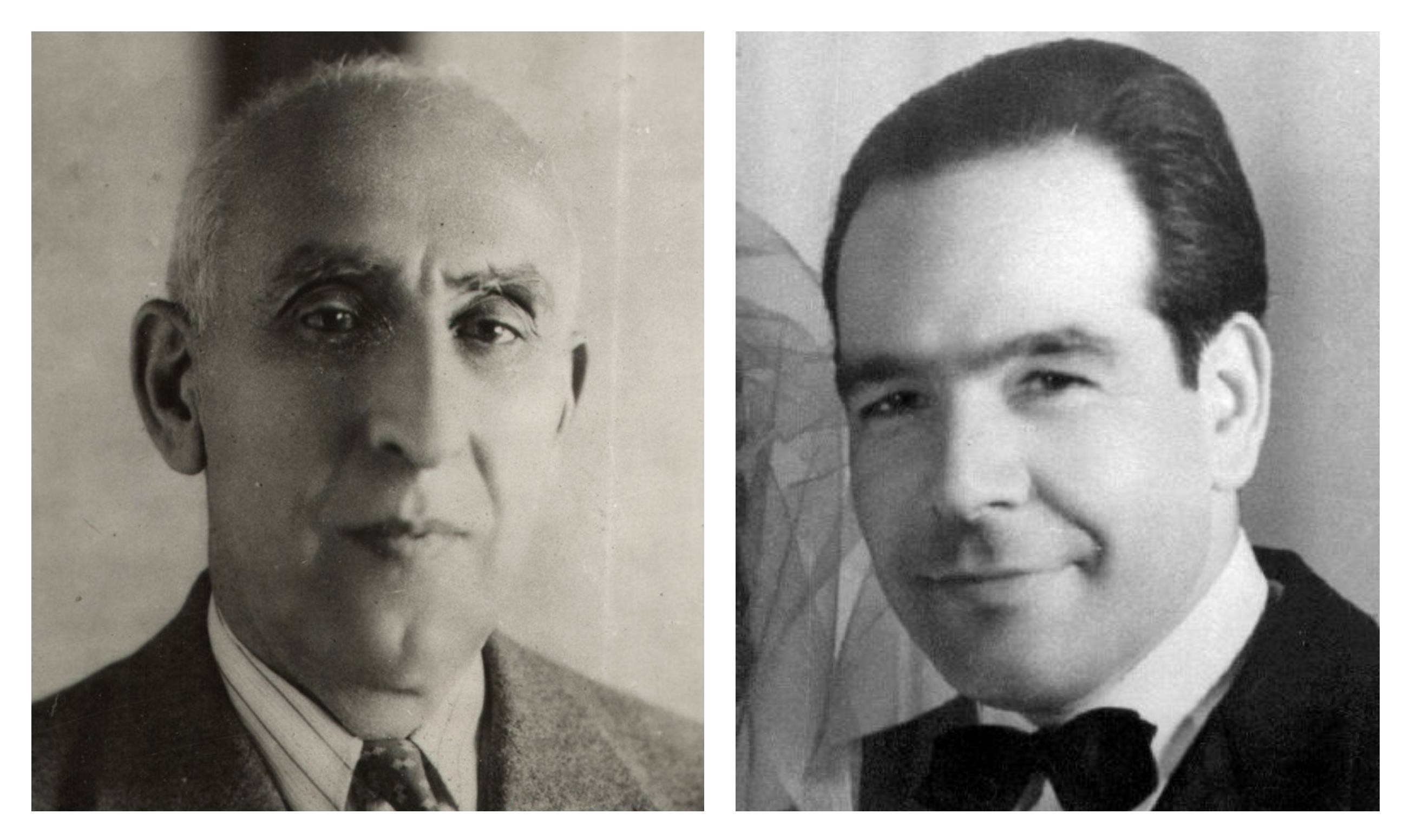

Iran, if it was to become independent of western dominance and have any chance at real development, would have to take back control of its oil wealth. That was the single-minded aim of Mosaddegh and his key ally Fatemi, who nationalised Iran’s oil industry by forming the National Front, a democratically elected and diverse body of politicians, journalists, scientists, clerics, and military.

But this democratic victory for Iran sank the economic interests of the US and the UK. Both countries, their post-war economies dormant, publicly lauded the bend of history toward freedom but privately agreed it was unacceptable for Iran. The UK in particular badly needed Iran’s cheap oil to recover from the war, with its cities leveled by German bombardment and its naval fleet converted to burn coal.

None of this could be said publicly. It would be reprehensible to have designs on the oil of a developing nation, whose large population lived in abject poverty. And so, the rationale and the plan for Operation Ajax was born: to prevent Iran from the threat of the Soviet Union, its wilful, naive prime minister must be deposed. It would be presented as a fight against the creeping influence of communism.

Today, the stealthy power of fake news to swing world events is familiar to everyone. But few are aware of how the CIA weaponised the press in the lead up to that summer of 1953, manipulating American, British and Iranian media to sway a contentious and existential political fight in the West’s direction.

Certainly Fatemi, now sitting in his cell in the palace barracks, despising the shah, the object of all his hatred for the West and its inflexible maw of greed, saw the propaganda - and now felt powerless to do anything. He was a newspaper man himself: well before 21st-century polling and algorithms, he knew the power of headlines to arouse tribal fears and indignation, to swell slender threats into monstrous proportions. After all, had he not rode populist headlines into high office himself?

As a young man he’d gotten his start at a small daily in Isfahan, working his way up to Bakhtar, a prominent newspaper in Tehran. Highly intelligent, and with fixed opinions about justice, Fatemi believed the Iranian public was being short-changed by a vacillating monarch in the pocket of foreign powers. That he was free to publish political cartoons and editorials that said as much meant something, but Fatemi, in all his youthful conviction, took that freedom for granted.

He spent four years in Paris during the mid-1940s earning a doctorate in journalism. When he came back to Iran, he saw the media more clearly than ever as a direct line to politics. How else was a boy from a humble family in the small town of Nain appointed the country’s youngest ever foreign minister at the age of 33, catapulted into the high politics that had for centuries been the domain of aristocratic statesmen?

The new foreign minister’s biting editorials and radio broadcasts resounded across the country. He was scathing not just about British machinations but also the Soviet Union, Iran’s domineering neighbour to the north, which had also infiltrated Iran's politics and press through the relatively small yet loud Tudeh political party.

Some considered Fatemi “a bit of a Ho Chi,” in the words of one Iranian diplomat, referencing Ho Chi Min, the revolutionary founder of modern Vietnam, who was then fighting for independence against the French. But when Fatemi was accused of being in the Russian pocket, he retorted: “Such support is not forthcoming, and even if it were, most assuredly it would be so laden with strings that its outright rejection is a given. Dr Mosaddegh would rather risk the collapse of his democratic government than be forced to accept Soviet support on undesirable terms.”

For the US operation in Tehran, the CIA’s own experimentation with fake news networks was auspicious. The agency had set up Operation Mockingbird, a systematic effort to reshape other countries’ politics by spreading the CIA’s worldview through the global media.

A gentleman spy for the agency called Donald Wilber was in charge of running the “war of nerves” against Tehran. His first task was to direct the western news agenda towards the fear of a Red Threat to Iran, portraying the country as dangerously close to being pulled into the Soviet orbit, and exaggerating the influence of the Iranian communist party, Tudeh.

Wilber paid off more than 20 newspapers in the UK and the US. He was on intimate terms with prominent American media figures including Henry Luce, co-found of the magazine Time and an old friend of the rising director of the CIA, Allen Dulles; and Arthur Sulzberger, publisher of the New York Times.

The British press attache in Tehran sent “a steady supply of suitable poison too venomous for the BBC” to the embassy in Washington, which disseminated it to the US press. American journalists, he later noted, made good use of the poison, and even let him draft some of their stories. Pieces painting Mosaddegh as an extremist playing with Soviet fire flowed through these outlets’ pages.

In London, the foreign office directed the BBC’s coverage of Iran and doubled the staff of the World Service’s Persian language service. The Times ran a series, likely drafted by the notorious academic spy Ann Lambton, describing the oil nationalisation crisis as a product of the faulty “Persian character", while “the horse-faced Oriental” Mosaddegh was a hysterical symptom of an old feudal order that couldn’t take responsibility for its own shortcomings.

As Fatemi’s columns and broadcasts grew more fiery after he became foreign minister, so the CIA agents running disinformation bought off more Iranian newspaper editors and journalists, paying them to run stories accusing the foreign minister of being in Moscow’s pocket, often on the basis of forged documents.

One operative later estimated the agency had infiltrated four-fifths of Iran’s newspapers. The BBC World Service chimed in from Bush House, on direct orders from MI6, Britain's foreign intelligence service, with bulletins calling Fatemi a dangerous extremist. The CIA planted stories accusing him of being gay, of him having Jewish ancestry or possibly being a convert from Islam to Bahaism, a charge intended to incite the same Islamic fundamentalists who tried to assassinate Fatemi during a speech in February 1952.

The injuries from that attack forced him to walk with a cane for life, and also hardened his politics. If your enemies were prepared to do anything, then you had to be at least a little ruthless to even stay in the game.

United Nations back Tehran - but US plots

In October 1951, Mosaddegh and Fatemi had taken the oil nationalisation fight to the United Nations, in Queens, New York. The British were demanding a vote at the Security Council in favour of their oil concession deal, plus damages for profits lost during Iran’s recent intransigence. Third World nationalism had not yet arrived in the halls of the UN.

Before Nasser, before Castro, before Arafat, it was Mosaddegh who addressed the UN. In flawless French, and at ease before the council, he laid out Iran’s sovereign right to control its resources, to allow them to flow for the development of its own people, who lived in disease and squalor. He mocked Britain for “trying to persuade the world that the lamb had devoured the wolf.”

When Fatemi spoke to the New York press corps, he introduced himself to reporters as “a man of the press,” with his allegiance to freedom of speech above all, in service to his country’s pursuit of independence. Freedom, he argued, was neither western nor eastern, comparing his nation’s plight to that of the fight for American independence from British rule in the late 18th century. He and the prime minister strove only to bring economic justice to the Iranian people. Diplomats at the UN went wild for it. Country after country backed Iran, and the council finally voted to postpone the discussion definitely.

Back in Iran, Mosaddegh's government expelled British diplomats and officials, charging them with domestic interference and plotting to rig the upcoming parliamentary elections. MI6’s front-facing agents were grounded. The British embassy was shut. Political channels blocked. Fatemi and Mosaddegh were in the ascendant. The British began weighing a clandestine final option.

By autumn of 1952, in both London and Washington, conservative and hawkish governments had aligned in power. Republican Dwight Eisenhower had replaced Democratic Harry Truman, who had seen in Third World anti-colonialism echoes of America’s own quest for independence.

And in the UK, a belligerent Winston Churchill had returned the Conservatives to power, succeeding a Labour government that was itself nationalising Britain’s industries and hardly inclined to block Iran from doing the same.

Both sides of the special relationship could now get on with a plan to take Iran’s fate out of her own hands.

Kermit Roosevelt, the wily, starchy, Panama hat and fawn suit wearing head of the CIA’s Middle East division, was the ideal front man. The grandson of President Teddy Roosevelt, Kim belonged to the smart set of old East Coast families who ran the CIA in its early days, and had the total trust of Allen Dulles, its director and the Roosevelts’ neighbour on Long Island’s Oyster Bay. His expertise was in stealth operations designed to shift local dynamics in America’s favor. Once he’d been dispatched by Dulles to wrest an oasis on the Persian Gulf out of the hands of sheikhs aligned with the British, so control could be handed to Saudis loyal to the CIA.

The time was ripe for Roosevelt’s craft of stealth. With Allen Dulles running the CIA’s covert operations, and his brother John Foster Dulles in charge of overt policy as secretary of state, the siblings from a zealous Presbyterian family pursued a path for US conduct in the world that rested on an ideological vision of racial nationalism: American interests were good and destined to prevail because they were American, white, and noble; while developing countries were inhabited by savages, their aspirations backwards, at times evil, and always crushable.

When President Gamal Abdel Nasser was setting up his security forces after Egypt’s independence from monarchial rule, Roosevelt pitched up to help him, offering a lavish budget to make Arab nationalism “hospitable to US interests.”

Roosevelt, who faced off against the KGB in Finland during World War II, fancied himself a Soviet-mole detector, and claimed to have been the first to notice something was amiss with Kim Philby, the British intelligence officer turned double agent, in Washington (Philby, in turn, described Roosevelt as the quintessential "quiet American").

All this had positioned Roosevelt nicely to moonlight for Overseas Consultants Inc, a consultancy venture set up by the Dulles brothers that signed massively lucrative deals with sympathetic overseas governments for US “advice”. Mosaddegh had unceremoniously cut Tehran’s contract with OCI in 1950.

In February of 1953, the British sent their new head of MI6, known as "C", to Washington, proposing that Roosevelt work as field commander in Iran. London’s working name for the planned coup was Operation Boot, but Roosevelt suggested Operation Ajax (it is unclear whether this was inspired by the Trojan war hero or the abrasive cleaning product). The US ambassador to Tehran, Loy Henderson, said he wished it was possible to just “starve Mosaddegh out of power” through sanctions and an oil blockade, but ultimately agreed to the plan.

Iran’s relatively open political climate and its lively independent press made it an easy target for shadowy campaigns to prepare public sentiment for regime change. The coup plans explicitly called for a media script to direct events.

The British agents involved, particularly the former MI6 Tehran station chief, now stationed in Cyprus, reminded the group of the importance of believing their own cover story: they were deposing Mosaddegh to avert the spread of communism, not to protect western oil interests. He later said: “When we knew where the prejudices were, we played all the more to those prejudices.”

Summoned to London, Roosevelt met with Churchill in late June. The rain beat against the windows of the foreign office. Roosevelt darted quickly up the grand staircase, not pausing to look up at the apricot marble pillars and showy vaulted ceiling, meant to inspire awe in imperial subjects. Once the team were assembled, a clerk with a long neck dropped a file before each place at the table.

There, they reviewed the logistical plan for Operation Ajax, which had been drafted in Washington and refined by British intelligence in Cyprus and Beirut. In London, everyone agreed the political mood was shifting. The shah was gaining confidence against Fatemi’s bombast, the prime minister definitively refused any compromise and the Iranian public, suffering from the economic strangulation of British sanctions, were tiring of what felt like endless antagonism with the world.

For Ajax to get off the ground, Roosevelt would assume cover as James Lockridge, a Canadian oil baron, and travel by land from Baghdad to Tehran to oversee logistics. There, he established himself in a villa in the north of the city. By day, “Jim” played tennis at the embassy and cultivated friends. By night, Roosevelt, through an agent codenamed Rosenkrantz, pursued a series of clandestine meetings with the shah.

15th August: Operation Ajax falters

After their tense exchange in the back of the Chevy in August 1953, Roosevelt watches the shah disappear into the palace lawn, his back straight even in the darkness. The CIA’s man in Tehran then bundles himself into the boot of the car, under a blanket that smells of mothballs. Once far from the palace, the vehicle parks in a dark alley. Roosevelt climbs out and drives himself into the sleeping city in an agency car, a British-made Hillman Hunter disguised as an off-duty taxi cab.

Roosevelt returns to the safe house victorious, having now secured the shah’s assurance that he will sign the royal decrees for the arrest and removal of Mosaddegh’s government. He spends the rest of the week by the pool, playing tennis, smoking and drinking vodka-limes, waiting impatiently for D-Day.

He plays Luck Be a Lady Tonight so many times that a fellow CIA agent, a paramilitary warfare expert, hides the record. The Persians, Roosevelt complains, enamoured of their millennia of history, like to procrastinate and call it deliberation. But 15 August finally arrives. An agent delivers the first coup report to the safe house: the arrest of Hossein Fatemi and the shutting of his provocative newsroom.

Still pacing in the palace prison, Fatemi, eyes now almost closed by the drying blood, worries about the prime minister. But across the city, Mosaddegh has been tipped off. On his orders, hundreds of loyal soldiers amass in the dark around his house, a stately Qajar mansion with colonnades and a private courtyard with a gurgling fountain. They are lying in wait for the turncoat colonel, Nematollah Nassiri, who heads the shah’s Imperial Guard. Following the coup's playbook, Nassiri carries the royal decrees ordering the prime minister's removal in his pocket.

A young loyal soldier, on lookout duty, is the first to see the light of the approaching Imperial Guard convoy. “They’re here,” he whispers. As the trucks stop on the drive leading to the house, soldiers loyal to the government melt out of the darkness and converge on them. A few gunshots ring out. General Taghi Riahi, the prime minister’s own general and chief of police, steps forward and personally arrests the turncoat colonel.

By one o'clock in the morning, the coup is over. It’s been a flop. The moon shines brightly over the empty streets. Pro-government soldiers crisscross town. Fatemi’s cell door swings open. He braces for the worst, as 10 soldiers rush in - but instead, they are solicitous. “Sir, do you have any orders for us?” they ask. He knows then that he is still foreign minister and not being rushed for execution.

When word reaches Roosevelt at the Lalehzar safehouse, he kicks the vodka bottles on the table in rage. Contact with CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, is routed through its operations in Cyprus.

Waking at dawn at his residence by the Caspian Sea, the shah, codenamed “Savoy” during Operation Ajax, hears about the failure of the coup on the 6am bulletin. That afternoon, he flees the country, along with Empress Soraya, flying first to Baghdad, then onwards to Rome.

The orders come back from agency chief Dulles: “Give up and get out now.” Roosevelt allows himself a vodka lime, assesses the extent of failure, and decides to push ahead like a man. He is a Roosevelt after all, in the mould of his grandfather, Teddy, the colonel and former US president, not his drunk father, also called Kermit, the black sheep of the family, who served the country in two wars but died ignobly, shooting himself in the head in an Alaskan backwater in 1943. Roosevelt cables back breezily from Tehran: “We’ve hit a small complication. But I’m staying on. All will be right in a few days. Love and kisses from the team.”

Snapped by press photographers outside a chic restaurant, the empress wears off-the-shoulder polka dot couture, her hair piled high and her expression haughty. The most glamorous royal in the world, the daughter of a Bakhtiari khan and a Viennese beauty, she speaks four languages and can outhunt and outride the shah. In Rome, despite having abandoned their country, she holds her head high enough for both of them.

In the days following 15 August, with the initial plan foiled, the monarchy imperilled, and Kim and his agents under the highest threat, Iran and Operation Ajax are both teetering on the edge.

On the morning of the 16th, Fatemi, fearful about retaliation from the shah and keen to take the situation in hand, descends on the prime minister’s house in a feverish state. He finds Mosaddegh reclined on his daybed, supine in his pyjamas, drinking tea from a slim-waisted glass and surrounded by his cabinet. To Fatemi, the old man is out of touch, dithering, with his plans to form a legal committee to constitutionally review the shah’s actions.

“We need a show of force, decisive action,” Fatemi insists. “Make me minister of defence this morning, and I’ll execute all the traitors in the army by noon.”

From behind the silver encased glass, Mosaddegh asks: “Under what law exactly?”

Fatemi responds, indignant: “You have concerns about law, when our country has been betrayed, by someone with no concerns about anything but his own interests? The revolution is its own law.”

The prime minister looks at him coldly. He has indulged Fatemi's idealism on many occasions, often shared his purity, but now they are parting ways. Mosaddegh has twice sworn an oath of fidelity to the shah, once on the Holy Quran itself. He is not a republican. His mother was a princess of the Qajar dynasty that ruled Iran for a century-and-a-half. He will not take his country over the cliff. “It’s my country too, and my law is the constitution. I have never opposed the monarchy, nor do I today, my dear Hossein.”

Fatemi is stunned, a little insulted. He does not propose this radical path because he’s some plebian reactionary. You have to read your enemy. Defend yourself appropriately. Can the prime minister, a seasoned politician three decades his senior, not see the British themselves are ruthless? That they are trying to starve the people into submission with sanctions? That they provoke the religious fundamentalists who shot him, leaving him with this shattered leg, forever leaning on a cane to just get across a room?

Fatemi limps out, pausing at the door: “Doctor, the legal approach you’re taking, in the face of the monarchy’s betrayal, is not realistic. It will lead to our end.”

16th August: Rallies and fake news

For safety, Roosevelt shifts his base of operations to the basement of the US Embassy, known as the “safest building in Tehran.” Occupying a 26-acre plot of land, it houses the largest contingent of American diplomatic employees anywhere in the Middle East. The shade of the ancient plane trees lining its grounds give some respite from the heat. When one of his lead agents suggest it is too risky to push forward, Roosevelt retorts: “Defeatist talk gets you shot.”

Around 7am, the CIA station chief wakes up two American foreign correspondents staying at the Park Hotel in Tehran, the old colonial era residence where English crime writer Agatha Christie used to stay. He summons them, one from the New York Times and another for the Associated Press, to a house in a posh district of north Tehran to hear the “real” account of last night’s events from General Fazlollah Zahedi, the outlaw politician Roosevelt is grooming to replace Mosaddegh as prime minister.

But Zahedi is in hiding. Instead, the journalists are greeted by his son Ardeshir, who provides them with copies of the shah’s decrees dismissing the prime minister, and a photocopied stack of a fake interview with his father, in which Zahedi claims he is the legitimate prime minister of Iran, and accuses Mosaddegh of staging a coup by ordering the shah’s arrest. The New York Times reporter returns to the Park Hotel and passes the interview around the lobby to fellow AP journalists.

That evening, a large crowd converges on Parliament Square for a rally sponsored by Mosaddegh’s party. Having failed to bring the prime minister round to his hardline logic, Fatemi appeals directly to the protestors for the establishment of a republic, effectively an end to the monarchy, and a trial of the coup “traitors”. His newspaper, Bakhtar-e Emruz, that same night publishes a lacerating account of the shah as a “capricious and bloodthirsty servant of the British.”

Protestors loyal to the prime minister mass around the city centre. Roosevelt senses he has only a short time to shift the dynamic on the street in favour of the shah, and dispatches one of his agents to two newspaper officers, with orders to splash front page headlines accusing the prime minister of expelling the shah.

The agent is one of the CIA’s most useful in Tehran, an Iranian journalist who works for the AP and the Daily Telegraph, along with a handful of Iranian newspapers. Roosevelt has nicknamed the operative, whom he finds swarthy, a “Boscoe bro”, after a brand of American chocolate milk. With forethought, the CIA recruited the agent in 1950 and brought him to Langley for training: having a talented press operative in your pocket is always useful when orchestrating such events.

As dusk descends on the city, the stark white tips of the Alborz mountains to the north etched across the sky, Roosevelt meets General Zahedi at the red light district brothel he is hiding in. Keeping the general, who has spent time in Germany and possibly collaborated with the Nazis, hidden and safe is crucial to the success of Ajax.

“Let’s move you somewhere more discreet,” Roosevelt says in broken German.

“Good. I was worried I would have to leave the country like the shah. Which wouldn’t be an entirely bad thing. German woman, Mr Roosevelt, exquisite.” Kim just raises an eyebrow, and gestures the lanky man to hurry along. “Soon you’ll be prime minister.”

Henderson, the US ambassador, who has ostensibly gone to Beirut “on holiday,” slips back into Iran that same night, flying into Mehrabad airport. He meets with Roosevelt at the embassy, and they confer on next steps. Henderson requests a meeting with Mosaddegh, and is offered an audience the next day. That night Kim and the ambassador drink martinis in the formal dining room under a portrait of Abraham Lincoln. They construct a plan, and Roosevelt is heartened that Henderson is so game. The State Department usually leaves dirty business to the CIA, but the ambassador is ready to advance the coup.

Late that night, Fatemi takes his case directly to the Iranian people in a radio broadcast, pleading for them to understand the stakes: “Make no mistake, foreign meddlers were behind this imperial coup. The enemies of our nation have shown their true face.”

Fatemi says that the shah may be handsome on the outside but is really a snake like Zahhak, an evil mythological Persian king who fed on the people’s blood. “He mopes around like a depressed victim, but know this... he will strike with venom when the time is ripe. We cannot allow a small-minded child to stab the country in the back while its people sleep. Awaken, brothers and sisters!”

On the morning of 17 August, Henderson meets the prime minister. The meeting lasts a tense hour. Mosaddegh wears an impeccable suit and a cynical, weary smile. Henderson mentions his “sorrow” over recent events. He then launches his diplomatic theatrics. He claims that Americans and their young children are being assaulted all over the country. That a diplomat’s car has been attacked and the driver stabbed. That mobs are surrounding the consul’s residence in Isfahan, chanting “down with the USA.”

If the attacks don’t end immediately, Henderson says with a sombre look, he will have to order the evacuation from Iran of all American citizens. The prime minister listens thoughtfully. Henderson then issues his threat. He’s heard that Mosaddegh is no longer even lawfully prime minister. Is he certain he is even a legitimate state authority?

The ambassador waits with some anxiety for the prime minister’s response. Mercurial and patrician, Mosaddegh is hard to read. Finally, he picks up the phone. Shaken by the challenge to his authority and fearful of the US cutting diplomatic ties at such a tenuous moment, he makes the fatal move that begins his undoing. Despite the thousands of Iranians converging on the streets in support, despite Fatemi’s ferocious defence of Iran’s right to control of its wealth and resources, Mosaddegh orders the police to clear the streets of his own supporters.

19th August: The shah cuts a deal

An eerie calm hangs over the city just after dawn. The leading parties under Mosaddegh’s control heed his instructions. No protestors wander out in public in the government’s name.

The CIA’s “Bosco Bro” has pitched up in newspapers offices overnight. Six major papers splash on their front pages a royal decree naming a new prime minister. Forgers paid by British agents have been up all night, producing fake leaflets pronouncing the dawn of Fatemi’s new republic, and his threats to hang the country’s most senior ayatollahs from lampposts. At the embassy, Kim plays solitaire to pass the time. Fatemi’s overnight offensive continues to blare from the embassy’s small RCA radio. Kim’s junior agents are working the phones, canvassing sources up and down the city for updates.

Around 8am, word comes that the street gangs Roosevelt has bought off are gathering at the central fruit and vegetable bazaar. Armed with knives and clubs, they are local toughs who work out at the city’s athletic clubs. A gang boss called Tayeb, to whom Bosco Bro has funneled CIA cash, directs his men to gather more young forces from the neighborhood. They then set off north shouting anti-Mosaddegh slogans, pounding on car hoods for drivers to honk in support of the shah. They beat up pedestrians, and tear down newspaper stands selling pro-government papers.

Tayeb, who controls gambling houses and brothels, summons the city’s most audacious prostitutes to join the crowd. This small hired mob of gangsters, street enforcers, thugs and sex workers continue to torch buildings and attack passersby. By the Ajax script, this is the spontaneous “royalist crowd” reflecting the Iranian people’s “popular will.” Its purpose is to distract.

The gangs loot offices and shops and wreak chaos, torching several political party and newspaper offices. They approach Fatemi’s newsroom. A Molotov cocktail streaks through the window of the daily, igniting the paper-strewn office. The foreign minister springs up from his radio address, cane in hand, stumbling to get out as the flames spread. His voice now cut off from the nation, Fatemi, on foot, heads north through the mayhem for Mosaddegh’s house.

The military unfurls across the city. The prime minister has directed his army chief to establish order, upon Henderson’s request, and tanks roll out from their barracks. This provides the opening for shah loyalists throughout the army to divert their soldiers to the original coup plans.

At the embassy, Roosevelt walks through the compound to the political counsellor’s house, switches on the radio, which now drones grain price broadcasts, and asks the counsellor’s wife for a sandwich and a vodka tonic.

The shah loyalists target pro-Mosaddegh commanders in various barracks, cutting off their communications. By late afternoon, 24 tanks converge on the prime minister’s house. Two are lethal American Shermans that roll into his garden, spraying bullets across the veranda and into the living room. The prime minister’s side is defended by three conventional tanks that are no match for such heavy bombardment.

In a short hour, hundreds of loyal soldiers, torn to pieces, lie dead among the rubble of the ornate courtyard. Under a dwindling firewall of bullets and tank shells from remaining loyal soldiers, the prime minister, Fatemi and several ministers flee, climbing over a wall to the neighbouring garden. They evade capture for the time being, but know that there is ultimately no way out. The army is backing the coup, its officer class historically staunch royalists who are indifferent to domestic politics. Cultivated and promoted by the shah, with their budgets and loyalty secured, they see no betrayal in moving against the prime minister on the orders of their monarch.

At around 2pm, Radio Tehran falls silent. The music abruptly stops. For long minutes, there is nothing. Then a breathy voice, too close to the microphone, booms the scripted lines: “We are announcing to the nation that the shah’s order to dismiss Mosaddegh had been carried out. The new Prime Minister Zahedi has taken office! His Imperial Majesty is on his way back home!” The voice also announces that a crowd has ripped the foreign minister to pieces. At home, Fatemi’s wife faints on hearing the news.

Roosevelt springs up and sprints across the compound. General Zahedi is in the basement of the ambassador’s residence, in his underpants. His pressed uniform is draped over a chair. The two men share no common language save some broken German, so Roosevelt grins widely and pumps his fists in the air to gesture victory. The general dresses swiftly, and crouches down on the backseat of a black Citroen. Roosevelt drives it west down Throne of Jamshid Street, and into a narrow alley, where the commander of the air force is waiting. There he places Zahedi on top of a tank and rolls into the streets, heading north for the Officers’ Club.

At the US embassy compound, Henderson waits in his sun-washed garden beside the swimming pool, a bottle of champagne chilling in a bucket of ice. Roosevelt rushes back, arriving at the same time as Zahedi’s young son Ardeshir, who has heard the news. They observe a short silence to absorb their victory.

The group toast the shah, the new prime minister, Eisenhower, Churchill, and of course each other. Henderson suggests to Zahedi that his father put a bounty on Fatemi’s head. He cables to Washington that if Fatemi remains active, he could reignite nationalist forces against the West. It is disappointing, the US ambassador notes, that Fatemi wasn’t murdered during the coup as initially reported. Making his way to the Officers’ Club, Roosevelt makes a toast there too: “One thing must be understood. You owe me, the United States, the British, nothing at all.”

The shah returns triumphantly to Tehran on 22 August, flying his own plane, just six days after his hasty departure. Waiting on the tarmac, amongst cheering royalists greeting the triumphant king, are Henderson, Zahedi, Shahban the Brainless and Ayatollah Kashani, the chairman of parliament. Soon after, the monarch cuts a deal with the United States and Britain that gives a consortium of British and US oil companies, including Anglo Iranian, later called British Petroleum, a 50/50 profit sharing agreement to last for 25 years.

Roosevelt visits the shah at the palace, and receives his thanks over caviar canapes and vodka. His duty dispensed, the CIA man catches a military flight to London, has an audience with a thankful, drowsy Churchill, and is feted by the foreign office at the Connaught Hotel. Back in Washington, Roosevelt receives a National Security Medal from Eisenhower in a secret ceremony.

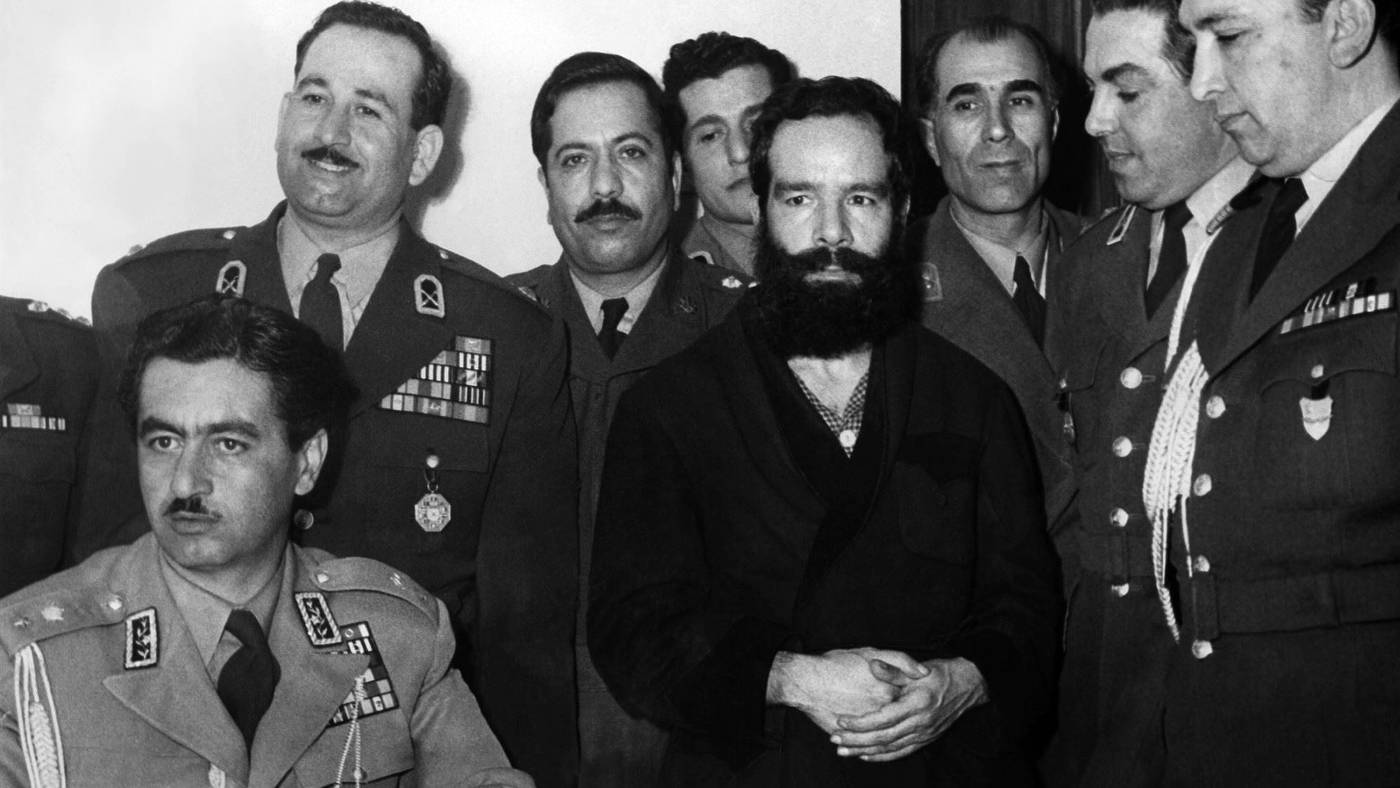

Fatemi goes into hiding, at first staying with friends but then, as the net tightens, reliant on safe houses. A few months later, a woman at a neighbouring house, on a lily-dotted mountainside suburb of Tehran, spots a bearded stranger on the balcony. She reports it to her husband, a policeman. Security forces storm the house. A policeman pistol-whips Fatemi’s head. When he is transferred to prison, Shaban the Brainless, the royalist street goon, stabs him eight times in the back and chest. Fatemi’s body is shattered by these injuries, but his conviction is steadfast. Even as his interrogators dangle offers of freedom and the prospect of a reduced sentence in return for admitting guilt and begging clemency from the shah, he still doesn’t waiver in his loyalty to a free and independent Iran.

His cellmate later recalls that although he was ill and barely able to sip water, Fatemi’s will was ferocious. “I had never seen anyone so brave in prison. A lion in chains will not kneel like a house cat.”

By the time he stands trial on 24 September, 1954, Hossein Fatemi, former foreign minister of Iran, is emaciated from torture and hunger strikes, his frame skeletal. The charges against him centre around alleged sedition against the monarchy in his editorials during the restive days between the two coup attempts. British diplomats involved in the trial recommend that “a cold-blooded execution might be the best answer for Fatemi.” In less than two weeks, the military court condemns him to death.

Fatemi’s wife and baby are not allowed to visit him after his conviction. At dawn on November 10th 1954, in the brisk chill of autumn, still dignified in a ragged burgundy robe, Fatemi is taken out to the back of the building and positioned in front of a four-man firing squad. As the soldiers raise their rifles, the foreign minister, the journalist, the radical, the anti-colonial fighter, roars: “Long live freedom! Long live Mosaddegh! Iran forever!” Eight bullets tear into him. His body crumples to the frozen ground. Fatemi was 37-years old.

Your obedient servant, Iran

Of the other key figures, Mohammad Mosaddegh spends two months in a military prison, and then is brought before a military tribunal on charges of treason. His trial is a national spectacle. He defends himself against the charges, claiming that his only sin was to nationalise Iran’s oil and expel the old and new imperial powers from Iran’s lands. The judge hands down three years in prison and house arrest for life, at his rural residence in Ahmad Abad. He dies there in 1964, aged 84, and is buried in his living room, erased from history, from school books, from newspapers, from the country’s collective imagination.

Kermit Roosevelt turns down the CIA’s offer to lead its next coup, in Guatemala. Instead, he prefers to go work for Gulf Oil, one of the beneficiaries of the new oil consortium. He dies in Maryland in 2000, also aged 84.

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi rules as shah of Iran until 1979. But after 1953, he suffers a permanent, irrational paranoia of American machinations, and a grievous doubt in his own authority. It triggers a suffocating regime of media censorship, ending the longest stretch of press freedom Iran has enjoyed in the 20th century. He is driven out by the revolution of 1979, first to the US, then Panama and finally to Cairo, where the last shah dies in in 1980, aged 60.

For Iran, the 1953 coup fatally erodes the honour and legitimacy of Iran’s monarchy. It creates a lasting and dysfunctional political culture of paranoia and suspicion of hidden hands. It triggers a suffocating regime of media censorship. It destroys the secular, non-Marxist, nationalist opposition, and ends the dream of oil nationalisation.

The CIA goes on to execute coups in Guatemala (1954), Indonesia (1957-59), Chile (1973) and Vietnam (1959-1963), among others. When the era of covert overthrow expires, the legacy of these actions, the mindset and private interests driving the myths of regime change and nation-building, live on through the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, resulting in the death of hundreds and thousands, and the displacement of millions.

During the tenure of Donald Trump, the United States again pursues a policy that amounts to attempted regime change in Iran, and seeks to destabilise the country through covert operations and economic strangulation.

Much of the country is plunged into poverty. US sanctions block Iran’s ability to import medicines and vaccines, and thousands of Iranians, men, women, and children, die from preventable diseases. Even US President Joe Biden refuses to allow Iran to buy Covid vaccines, and the country experiences one of the world’s highest death tolls from the pandemic at time of writing.

For decades now, each successive generation of educated young Iranians, their hopes and prospects blighted by Iran’s seemingly permanent isolation in the world, calls itself “the burnt generation.”

Azadeh Moaveni directs the Gender and Conflict Project at the International Crisis Group. She has reported on the Middle East for two decades, and her latest book, Guest House for Young Widows, charts the lives of women mobilised to the Islamic States. She teaches journalism at New York University’s London campus and writes often for the New York Times and other publications.\

https://www.middleeasteye.net/big-story/iran-us-uk-oil-friends-fall-apart-cia-coup

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home