“A Real Flood of Bacteria and Germs”: Communications Intelligence and Charges of U.S. Germ Warfare During the Korean War

Cover art for CIA pamphlet release in 2013, in public domain.

In February 2013, the CIA posted over 1300 items online as part of their earlier “Baptism by Fire” document release commemorating the 60th anniversary of the start of the Korean War. The bulk of their accompanying narrative material concerned long-time controversies as to whether the CIA had failed to anticipate both the North Korean invasion of the Republic of Korea in June 1950, and the Chinese entry into the war later that year.

In order to provide a documentary backdrop to a history of the war from an intelligence point-of-view, the CIA also released hundreds of declassified top-secret communications intelligence (COMINT) reports, as well as assorted formerly secret intelligence analyses, and open-source reports from the Agency’s Foreign Broadcast Information Service (FBIS).

The CIA likely did not set out to document the COMINT history of the North Korean and Chinese response to what appeared to be U.S. and/or U.N. attacks by biological, bacteriological, or ”germ” weapons, but that is in effect what happened.

While the released documents do not represent a full opening of all archives related to Korean War communications intelligence, the sampling is unprecedented, and the contention of this essay is that the released files provide a valuable addition to our understanding of the events surrounding the alleged U.S. biological or germ warfare attack against North Korea and China from 1950–1953.

This essay draws upon 28 COMINT documents, produced by communications intelligence units and labeled top secret, in addition to 11 other CIA analyst reports previously marked “secret,” one report marked “top secret,” two reports marked “confidential,” and one marked “restricted.”

The COMINT documents were all labeled “Top Secret,” with additional compartmented code words, such as SUEDE or CANOE, for more restricted intelligence circulation. Among COMINT producers and customers, these documents were considered “Special Intelligence,” so secret and restricted even their code words were classified.[1] Most of these items were not declassified until about 60 years after the end of the Korean War.

A table listing all biological weapons attacks documented in the SUEDE and CANOE COMINT documents is included prior to the Notes section below. In addition, a full set of the 28 COMINT documents, along with relevant sections from other CIA reports, is available for download in PDF format at the end of this article.

No full analysis of these documents released by the CIA has ever been published. So far as I can determine, only one historian of the period has even referenced them.[2] It is important that they receive attention, as the question of the guilt or innocence of the U.S. when it comes to charges of the use of biological weapons of mass destruction during the Korean War has never been fully settled.

These documents provide strong corroborating evidence that the germ warfare charged by the Communists, and by a number of outside observers, journalists and investigators, did in fact occur. The consilience of evidence includes the testimony of U.S. Air Force and Marine personnel captured by North Korea and China, though that evidence will only be examined here in the context of how it arises in the relevant CIA documents. Conversely, the evidence pertaining to other theories about the germ warfare charges, e.g., that it was a “hoax,” lack such convergent evidence.

This essay sets out a history of the germ warfare campaign as experienced and reported by North Korean and Chinese military units, filtered primarily through daily COMINT reports of Communist communications contemporaneously gathered by U.S. military intelligence. Contemporary CIA-based open source information will also briefly be examined.

This essay will first briefly look at the U.S. communications intelligence situation at the start of the Korean War. Then it will examine closely the COMINT and other recently released CIA declassified documents, concluding with some examples of their historical relevance in the light of the Korean War scholarship of Milton Leitenberg. Leitenberg, who has been quoted widely, has published documents that he purports show the charges of biological warfare (BW) made by the Soviets, North Koreans, and Chinese, were false, and that evidence was manufactured to perpetuate the supposed fraud.[3]

For the purposes of this essay, most references to Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) include references to COMINT, as the latter is a subset of SIGINT. Practically speaking, COMINT refers to the interception of communications, often encrypted, between two individuals or organizations. SIGINT is more narrowly understood as the interception of electronic signals, such as telemetry, from the enemy.

COMINT at the Start of the Korean War

When the CIA posted the Baptism by Fire documents in 2013, they included historical articles they felt were relevant concerning the history of communications intelligence as it pertained to the CIA during the Korean War. The summary in this section draws upon those accounts, as well as other publicly available material, as noted in the endnotes.[4]

By all accounts, along with a general drawdown of forces in Korea in the period 1948–1950, after the end of the U.S. occupation of South Korea and the start of the Korean War, communications intelligence resources in Korea were minimal. Even more, there was a good deal of bureaucratic infighting between the different branches of the military and between the military and the new CIA over who had access to the limited amount of material available.

Once the war started, even after the initial problems appeared to be addressed, the problems of ill-coordination and poor infrastructure continued. For instance, Marine Corps units on the ground apparently never had access to signals intelligence (including COMINT) during the war. In addition, there was an ongoing dearth of linguists available to translate the materials obtained, necessitating a rather long delay for intelligence and military consumers.

According to an NSA-published history, at the beginning of the Korean War the Armed Forces Security Agency [AFSA] (the predecessor to the National Security Agency), only “had the equivalent of two persons working North Korean analysis, two half-time cryptanalysts and one linguist.” There were 83 analysts working on data from the People’s Republic of China. Months later, in early 1951, AFSA had 49 personnel working on North Korean communications, and 156 on China.

The same historical account states, “COMINT production was hampered by supply shortages, outmoded gear, a lack of linguists, difficulties in determining good intercept sites, and equipment ill-suited to frequent movement over rough terrain.” Most radio equipment used was of World War II vintage.

In a retrospective essay, Thomas J. Patton recalled his days working for CIA’s General Division, which was the analyst unit within CIA that was to provide intelligence from raw COMINT intercepts: “We never had a clear concept of what proportion or what level of clandestine information we were given access to.”

“We may have had access to some State Department traffic, but we could never be sure of receiving it, and we could not have used it directly in any event,” Patton wrote. “And our access to information from military sources was always uncertain….”

“Physical handling of information was of necessity fairly primitive in those days. There were no copying machines. Most items that we received came in single copies, which we had to pass on and could not retain for our files.”[5]

Despite all the difficulties, in the early days of the war, by mid-July 1950, AFSA had achieved some success in intercepting and decrypting North Korean messages. The new information was so good that, according to Thomas R. Johnson’s 2001 article, “American Cryptology During the Korean War,” during the famous summer 1950 defense of the Pusan perimeter, with US and UN troops backed into a corner by a successful North Korean offensive, “General Walker…. was able to hold the line largely due to knowing where the North Koreans were going to attack, information coming primarily from SIGINT reports.”[6]

Despite the early successes, the signals and communication intelligence aspect of the war played out in a cat-and-mouse fashion. American successes were foiled by changes in Chinese and North Korean communications. The U.S. forces would catch up, and then lose their ear into enemy communications again.

There were multiple communications intelligence efforts by different agencies during the war, and they weren’t always well coordinated. The Air Force Security Service ran its own separate operation for some time. The signals and communication intelligence assets in the Naval Security Group remained focused on the Soviet naval presence in East Asia, and not on North Korean or Chinese targets.

The general dissatisfaction with the U.S. SIGINT and COMINT work was captured in a communication from General James Van Fleet, commander of the U.S. Eighth Army:

“It has become apparent, that during the between-wars interim we have lost, through neglect, disinterest and possibly jealousy, much of the effectiveness in intelligence work that we acquired so painfully in World War II. Today, our intelligence operations in Korea have not yet approached the standards that we reached in the final year of the last war.

“Much of this dissatisfaction centered on AFSA. At the same time, the senior officials of the State Department and the Central Intelligence Agency also felt AFSA was less responsive to their needs than it should have been.”[7]

As CIA historian Johnson concluded, “What tactical successes there were, were gained only after long delay and prodigious effort. Unready for Korea, American cryptologists rose unsteadily to the challenge and were knocked down several times by enemy haymakers. Resources were inadequate. Organization was sometimes chaotic, and expertise had to be acquired laboriously. Still, SIGINT did make a difference on a number of occasions. It was not quite what had been achieved in World War II, but it did establish the outlines of a successful tactical SIGINT support system.”

The problems with SIGINT and COMINT led to a significant effort by the Truman administration to reorganize resources and administrative authorities. By November 1952, this led to the establishment of the National Security Agency.

It is against this history of both success and failure that we turn now to the extant COMINT cables released to the CIA, and the intelligence commentary that was subsequently produced by CIA analysts. The material in these cables and reports can then be compared to other existing histories with their own accompanying evidential foundations.

The BW Timeline

1949 Khabarovsk

The following material is described in a mostly chronological fashion, the better to understand the unfolding portrayal of both the Communist charges of BW and the CIA’s own contemporaneous characterization of them. By adhering to this approach, contemporaneous observations and conclusions regarding the purported germ warfare campaign are not contaminated by later retrospective findings or changes in agency or governmental policy.

As a whole, the examination of the CIA material will be long and somewhat detailed, as one important aim of this article is to provide researchers with a comprehensive dataset for reference purposes. Since the CIA released very little that covered the first 18 months of the Korean War, the examination of the first period will be brief, and is mostly, though not entirely, limited to the new material released. It is not a comprehensive examination of that period, and presumes some knowledge of the history of the Korean War.

The other historical incident of relevance predates the Korean War. The appropriate starting point for this history is the December 1949 Soviet war crimes trial of doctors, researchers and military personnel associated with Japan’s biological warfare program. The results of the trial, including lengthy portions of the transcripts, were published in English[8], although it appears, according to one scholar, “few people in the West, including journalists and professional historians, paid any serious attention to the trial and its published proceedings until the 1980s.”[9]

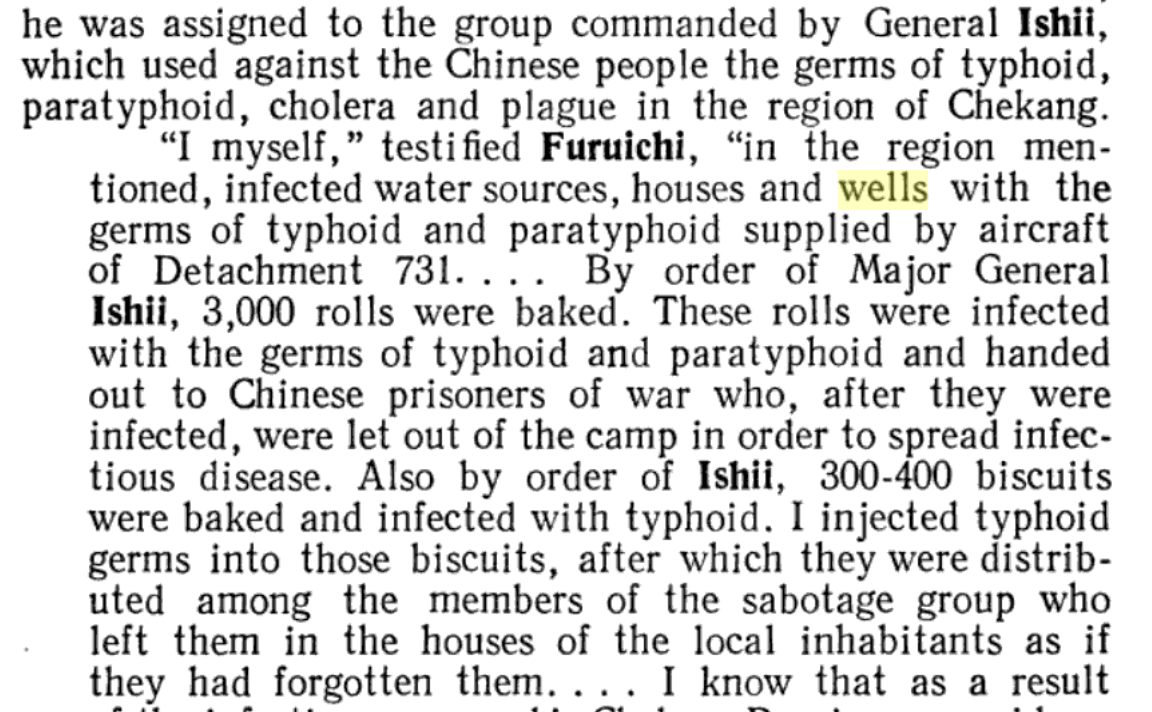

The trial established that Japan’s Unit 731 and other assorted bacteriological units, experimented upon plants and animals for the purpose of biological warfare, in addition to engaging in criminal human experimentation, including vivisection. At least 3,000 prisoners died in this fashion. Many thousands more died in BW campaigns waged by Japan’s Kwantung Army in China during World War II.

The United States made an agreement with the leadership of Unit 731 not to prosecute their personnel at war crimes trials, and the U.S. thereby would receive the technical reports and testimony from personnel of the results of Japan’s BW campaigns. U.S. scientists from Ft. Detrick interviewed Unit 731 leader Shiro Ishii and others, and the information was closely held in “intelligence channels.”[10]

Publicly, the U.S. derided the Khabarovsk trials as Soviet propaganda. Japan’s use of BW during the war was considered “a ‘dead issue’ by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East.”[11] Much later, scholars determined the Khabarovsk trials had involved real war crimes associated with the Japan’s use of biological warfare. The Soviets and Chinese were well aware of Japan’s use of BW at the time, since they were the targets of the attacks.

The Soviets in particular were incensed at the lack of cooperation from the U.S. over the issue of trying Ishii and others, including the Emperor of Japan, for war crimes concerning use of bacterial weapons. They knew, for instance that the U.S. had hidden from them the location of Shiro Ishii after the war. Hence, in the years after the war they were quite suspicious of what the U.S. was doing with their contacts with the former Japanese BW program leaders.

1950–1951

The documentary material CIA released for the first 18 months of the war is sparse, at least as it concerns information about the biological warfare charges. Still, what was released is intriguing and worth investigating, especially since this period of the war has been overlooked or minimized by most investigators of the Communist BW charges.

A 1951 retrospective CIA report by the CIA’s Office of Scientific Intelligence, “Communist Propaganda Charging United States with the Use of BW in Korea,”[12] stated that prior to the start of the Korean War, the chief of the Epidemic Prevention Bureau in the North Korean Ministry of Public Health had warned about the possibility of epidemics in summer 1950 originating from South Korea, “where no preventive measures had been undertaken to combat them.” The CIA report said that it was only after the war began that the United Nations started a vigorous immunization campaign in the South against smallpox, typhus, typhoid, and cholera.

According to this CIA report, sometime in July 1950[13] North Korean forces occupying Seoul claimed to have discovered “in the intelligence offices of the General Staff of the South Korean Army documents written in rather technical detail and designated ‘Plan A’ and ‘Plan B.’ One of the chapters was labeled “Bacteriological Dissemination.” This chapter “supposedly mapped out reconnaissance work for 1950 and described how rivers and reservoirs of North Korea were to be infected with bacteria.” The sourcing of the “capsules of bacilli,” i.e., “from American Camp Detrick or from Japanese stocks,” was not settled.[14]

Contaminating wells and water sources with bacteria was a favored method of Japan’s Unit 731. This is noteworthy, as it was believed, as described above, that personnel from Japan’s BW command were aiding the US war effort. Indeed, an early January 1951 report by Pravda, picked up by Associated Press on January 7, claimed the U.S. had “established a bacteriological warfare center in Japan under the direction of former Japanese Lt. Gen. Shiro Ishii.” AP also quoted Pravda as saying Ishii’s work for the Americans was being sent from Japan “to an American bacteriological warfare research center at Camp Dietrich [sic], Md.”[15]

One notorious incident early in the war comes from Peter Williams and David Wallace’s book, Unit 731: The Japanese Army’s Secret of Secrets.[16]Williams and Wallace recount the testimony of a British platoon sergeant with the Middlesex Regiment, who along with all UN troops were in headlong retreat from a major Chinese offensive into North Korea in November 1950.

The sergeant related seeing American military police in unidentified vehicles, wearing white helmets, parkas, gloves and masks, entering houses in a village “twenty to thirty miles south of Kunari.” The MPs were spreading feathers among the houses in the village, out of containers “with snapfasteners reminding me of our ‘Dixie’ containers, which were used to keep food warm for twenty-four hours.”

According to the British sergeant, “They were holding the feathers at a distance from their bodies, not in the normal way….. they had no identifying insignia…. It was all very fishy. They were very surprised and unhappy to see us. It was obvious that something suspicious was going on, and that it was a clandestine affair.’”[17]

Williams and Wallace comment that the use of infected feathers as a special BW tactic during an armed forces retreat was a standard method used by Unit 731 during World War II. “Furthermore,” they wrote, “it is known from declassified documents that the Biological Department of the US Chemical Corps was at this time experimenting with feathers as carriers of biological agents.”[18]

On December 5, 1950, the U.S. Department of Defense Committee on Biological Warfare issued a directive urging a search for “evidence of immunity against diseases of BW importance in enemy deserters and prisoners of war.”[19]

Later that month, during the U.S./ROK/UN chaotic retreat from North Korea after the entry of China into the war, the North Korean Ministry of Public Health claimed the Americans had “infected four cities with smallpox — another disease previously unknown in Korea.”[20]

According to reporter Wilfred Burchett, then in Korea, “Epidemics broke out in Pyongyang, Chongjin, Kuwon and Yongdok, in each case six or seven days after American troops withdrew. The incubation period for smallpox is ten days and the bacteria must have been spread a few days before withdrawal. The bacteria were found to be of artificial culture — and in this case less virulent than the natural variety. The four cities are widely separated, but the epidemics broke out simultaneously and no other centres were affected. The cities were not connected by the retreat route, that is to say troops withdrawing from Chongjin, did not pass through Pyongyang, Yongdok or Kuwon and vice-versa, so the epidemic — even if started naturally — could not have been transmitted by the troops. And in any case there were no outbreaks in intermediate towns or villages.” Altogether, some 3,500 people were reportedly infected with smallpox, and 358 died, mostly babies.[21]

According to the CIA, earlier in the year, reports “disseminated by Communist sources” said “that plague carrying fleas have been employed by American forces to spread plague in Korea. The Communists claimed in 1946 MacArthur sent eighteen Japanese bacteriologists to War Department laboratories to continue the culture of BW agents.”

The CIA also described Chinese claims that “Chinese Communist prisoners were subjected to bacteriological experiments on a small island outside Wonsan…. the Chinese Red Cross has revealed the Americans are testing bacteriological weapons on captured Chinese volunteers and gruesome experiments are being conducted under the guise of epidemic control.”[22]

These experiments are likely a reference to the Sams incident in March 1951, wherein a Navy epidemic control vessel, commanded by MacArthur’s Chief of Public Health and Welfare Section, U.S. Brigadier General Crawford Sams, made raids upon North Korean territory, with plans to kidnap North Korean personnel and take them back to the U.S. ship, reportedly to be tested for bubonic plague, smallpox and other diseases. This act of covert medical surveillance was later admitted, though the U.S. denied any experiments were conducted, and said no prisoners were actually kidnapped.[23]

In the end, Brig. Gen. Sams said that no bubonic plague was found, only hemorrhagic smallpox.

A late March 1951 CIA report noted that in the last week of March, Radio Pyongyang had “twice reported with credit lines to Tass and NCNA [New China News Agency] that MacArthur is preparing for bacteriological warfare in Korea.”[24]

The accusations continued into the spring. [ADDENDUM, OCTOBER 16, 2020: According to A.M. Halpern in a 1952 Project Rand report, “Bacteriological Warfare Accusations in Two Asian Communist Propaganda Campaigns,” a Chinese April 30, 1951 broadcast claimed “American forces are using People’s Volunteers as guinea pigs for their bacteriological experiments.” Japan’s government was described as producing bacteriological weapons in Minami-Kuwata-gun near Kyoto, in association or collaboration with “Camp Detrick” in the U.S.]

On May 8, a North Korean radio broadcast accused “US and ROK forces of employing biological warfare” against civilians in the North. According to a CIA report that same month, the broadcast referred to “documents concerning plans for the use of BW, allegedly captured from the ROK.”

The CIA report quoted the broadcast as saying, “American Armed Forces had contaminated with smallpox the inhabitants in the areas of North Korea temporarily occupied by them.” The broadcast also stated that while no smallpox had occurred in North Korea for at least the past four years, there had been a widespread outbreak “7 to 8 days after liberation of [North Korean] areas from American Occupation.”[25]

But the CIA report commented, “these claims may be an attempt to conceal the failure of North Korean public health authorities to prevent the outbreak of communicable diseases. While the incidence of smallpox to date in North Korea is unknown, [about 4–6 words redacted] reported the outbreak of smallpox earlier this year.”[26]

During this period, one CIA report, dated May 24, 1951, speaks to the intensity of the civil war conflict in Korea.

“On May 22,” the CIA report states, “ROK Ministry of Health released stats on 400,000 men held in ‘training camps.’ 13,000 died in April, while 200,000 suffered from hunger and malnutrition.” The CIA commented, “Prior to the 2nd Communist capture of Seoul in January, the ROK government rounded up all men of military age and sent them south under guard to prevent their conscription by the Communists. The men were held in virtual concentration camps in the south and no ROK Government agency would accept full responsibility for their maintenance. Some 250,000 of the 400,000 were recently released.“[27]

Meanwhile, a May 24, 1951 open source report by CIA’s Foreign Broadcast Information Service cited a May 8 dispatch from DPRK Foreign Minister Pak Hon Yong [alternatively, Pak Heon-yeong] “protesting American use of bacteriological weapons,” and claiming the U.S. was emulating “Japanese Bacteriological Criminals.”

Pak returned to allegations of a “Plan A and Plan B” discovered in “ROK headquarters in Seoul,” consisting of “sabotage plans, based on use of bacteria, against vital North Korean installations, towns, and army units.”

The CIA report continued: “Pyongyang alleges that the U.S. is following Japanese bacteriological techniques used in the war against China, and asserts that MacArthur used Japan as an intermediary in the mass production of bacteria. Other comment imputes responsibility for the incidence of smallpox in North Korea to the spread of the germ by the Americans during their temporary occupation. Pyongyang comments that the ‘bestial attacks of the American invading troops against the Korean people have done nothing but enhance the fighting spirit of the Korean People’s Army units.’”[28]

Some three months later, an August 11 North Korean radio broadcast described a government complaint to the UN about U.S. use of “poison gas.” According to an August 14 CIA report, “The broadcast cites the 6 August dropping of two ‘bombs’ on the city of Yonan (southwest of Kaesong) and the 7 August bombing of a North Korean troop installation as evidence of… ‘deliberate atrocities.’”

The CIA analysts commented: “North Korea has previously accused the US of employing chemical and biological warfare. These accusations are probably for Soviet Orbit internal consumption in order to strengthen the ‘hate America’ feeling.”[29]

An August 20, 1951 secret report, “Communist Propaganda Charging United States With the Use of BW in Korea” looked back at the charges of the previous month and concluded they were lies and “distortions of facts” directed from Moscow. “Charges of inhuman methods of warfare by bacteriological means would have a definite emotional and psychological effect upon those nations considered ‘on the edge’ in political affiliation,” the CIA analysts wrote.[30]

According to the CIA, Communist-held areas suffered from outbreaks of typhus and smallpox. (ROK-held areas were battling a typhus epidemic as well.) “All civilian doctors have been mobilized,” the report stated, “penicillin and other drugs have been confiscated for Communist Army needs.”

According to the report, Soviet sources alleged, “MacArthur’s headquarters in Japan was purported to have been producing bacteria with the aid and assistance of unpunished Japanese war criminals. For this activity the Yoshida government had appropriated 1.5 million yen…. Reports have also been disseminated by Communist sources that plague-carrying fleas have been employed by American forces to spread plague in Korea.”[31]

The charges of BW use by the Americans continued sporadically. According to an October 1951 CIA report, a pamphlet from the World Federation of Democratic Women, entitled “An Eyewitness Account of the Modern War of Destruction,” appeared in Austrian Communist bookstores, and included a description of the alleged BW campaign.[32]

CIA’s “Baptism by Fire” Release of Top Secret COMINT

1952

The CIA “Baptism by Fire” collection concentrated its release of COMINT documents on the year 1952, which also was the year of the most intense allegations of U.S. use of BW in the war. The following is a chronological timeline of North Korean and Chinese contemporaneous reports of US-led biological warfare during the Korean War during the presumed height of the latter campaign in 1952 and 1953.

The first of the 1952 CIA documents released is dated February 19. The documents do not include an earlier reference to “flies, fleas & spiders found & examined from Peng Kang Goon, Kang Won Province” on January 28, 1952, as mentioned in the “Report on U.S. Crimes in Korea” by the International Association of Democratic Lawyers.[33]

By mid-to-late February, intercepted communications indicated that North Korean military units had begun to be negatively affected by UN BW operations. A North Korean coastal security unit in eastern Korea reported on March 3, “UN bacteriological warfare agents” in the area surrounding “Pupyong (just southwest of Hamhung)” had prevented the movement of transportation since February 21.

As a result, no one could pass through the area, and crucial supplies were bottled up. “If you do not act quickly,” the unit said, “the 12th and 13th guard stations will have fallen into starvation conditions.”[34]

Another Top Secret “SUEDE” intercept from this period noted insects were “again dropped at Paekyang, Sinpung, and Innam,” on February 28, “but ‘no one has been infected yet.’”[35]

A Top Secret SUEDE report, dated February 19, quoted a February 16 North Korean intercept from a battalion of the 7th Railroad Security Regiment in the Wonson-Hamhung area to the effect that “spies are putting poison into the drinking water.” Some kind of “paper which causes death to ‘anyone using… [it] for the nose,’” was also mentioned.

The same report also documented a February 27 message to a North Korean battalion commander, informing him to “take special precautions to avoid contamination of his unit’s food and water because ‘the enemy dropped bacteria’ in central Korea. Covering wells and disinfecting United Nations leaflets were additional recommendations.”[36]

Meanwhile, just a day earlier, according to yet another SUEDE intercept, an unidentified Chinese Communist unit reported, “yesterday [February 26] it was discovered that in our bivouac area there was a real flood of bacteria and germs from a plane by the enemy. Please supply us immediately with an issue of DDT that we may combat this menace, stop the spread of this plague, and eliminate all bacteria.’”[37]

To the CIA, such reports were made to “provide the Communists with the ‘proof’ which they apparently require to support a propaganda campaign.” The analyst working on the February 26 intercept believed this report to be only “the second instance during the current BW scare that a Communist field unit has actually reported the discovery of ‘UN bacteriological agents.’”[38]

By the end of February, it was obvious to the CIA that a large-scale immunization campaign was underway among Chinese and North Korean troops. On February 27, a message from a Chinese Communist artillery regiment reported, “we have now fully obtained the vaccine required for smallpox in the spring time, malaria, and bubonic plague.” The regiment’s message explained that the smallpox and malaria shots had been given, but asked, “How shall we administer the bubonic plague shots?”[39]

On February 29, Chinese military authorities informed an artillery unit (perhaps the same artillery unit referenced in the February 28 message) that “all personnel will be reinoculated at once” with bubonic plague vaccine. Healthy individuals, however, were to only receive “a half-strength shot or may ‘temporarily not be inoculated.’”[40]

During the same period, a series of North Korean messages from a coastal defense unit were intercepted on February 28 and 29, though the CIA document doesn’t say to whom or from whom the messages originated. The message described instructions to cover any BW “contaminated area … with snow and spray… Do not go near the actual place,” the message’s author(s) warn. Meanwhile, “injections” with an unidentified vaccine were to be made to deal with the contamination. Another message also stated, “the surgical institute members left here to investigate the bacteria bombs dropped on the 29th.”[41]

To the CIA analysts reading these reports arriving from the Armed Forces Security Agency in early March 1952, it appeared that bacteriological warfare in Korea was now a “major Communist propaganda theme.” The COMINT reports themselves were marked Top Secret, labeled with the code word SUEDE, so that no one who was not approved for SUEDE reports could read them, even if they had other top secret clearances. [42]

One such report, dated March 1, described how “protest meetings,” in the form of lectures, were being held among North Korean troops to supposedly intensify “hostile feelings” regarding the UN forces’ bacteriological attacks. Somewhat humorously, one North Korean east coast defense unit was admonished to “make sure they (the troops) are awake at the lecture.”[43]

On March 1, there was a query from Pyongyang authorities to a North Korean air unit at Sariwon, in an area supposedly contaminated from bacteriological attack. “Have you not had any victims as a result of certain bacteria weapons?” the air unit was asked.

Five days later, the North Korean 23rd Brigade sent a “long detailed… message to one of its subordinate battalions” suggesting preventive measures be taken against “bacteria” dropped by UN aircraft, apparently in the area around Sariwon. The report stated that “three persons. . . became suddenly feverish,” presumably in their unit. Their nervous systems were said to have become “benumbed.”[44] Despite treatment, one of the three had died. The report concluded, “the government will soon take pictures of specific appearance of the germs collectively and correct photographic data will be provided.”

That same day, March 6, a “Chinese Communist message” stated that a soldier of the 345th Regiment had picked up a UN propaganda leaflet and had been “immediately poisoned.” The message said that the soldier, who had come down with a fever, did recover. Meanwhile, the CIA analyst reading this intercept noted in his report that this was the second time in which sickness had been related to “UN leaflets.” The Chinese message warned other military units “not to handle leaflets.”[45]

On March 11, two coastal security stations in northeastern Korea reported on 11 March that a “bacteria bomb” had dispersed mosquitoes, flies, and fleas. A second report noted, “an enemy plane dropped ants, fleas, mosquitos, flies and crickets.”[46]

The next day, US forces intercepted North Korean naval messages to units in Songjin and Chongjin, which are cities in coastal northeastern Korea. The messages ordered these units to cooperate with city officials, who had “a counterplan” against the bacteriological attacks via insect vectors. The plan called for “injections, vaccinations and rat poison,” noting, “to prevent an epidemic the rats… must be hunted.”[47] The type of disease is not described, but the emphasis on rats would implicate plague.

Meanwhile, around this same time, a Chinese intercept described a “Communist unit commander in western Korea” instructing his subordinate unit, who had captured some UN soldiers. The subordinate unit was told to ask the prisoners what “type of immunization shots were administered recently… in preparation for defense against what disease,” and “what type of common literature (was) made available regarding disease immunization and prevention.”[48] It would seem that Chinese authorities were still trying in early to mid March 1952 to determine what kinds of biological weapons were being aimed at them.[49]

If this was a “hoax,” then why conduct interrogations about “immunization shots” or disease prevention literature?

It’s clear that the region was under severe stress from the destruction wrought by war, and that included outbreaks of disease. The COMINT reports sometimes comment on various epidemics and health statistics, many of which were not attributed to biological attack, even if in public propaganda authorities denied epidemic conditions. As an example, one Top Secret SUEDE document noted a “Russian administrative message” from a “military net in northwestern Korea” reporting ”an epidemic of typhus” in local villages. “Please urgently send. . . assistance,” the message says.[50]

But plague was always associated with BW attack. On March 15, another “Chinese Communist message” announced, “a certain unit discovered a large concentration of plague germs. Many people have been afflicted with this undiagnosed disease and already several persons have succumbed with the illness.” The very next day, a Chinese Communist unit’s communication described four preventive measures for carrying out an “anti-smallpox campaign,” as well as an “anti-plague program.”[51] The unit was not otherwise identified.

A March 17 COMINT daily report states, “Approximately 60 percent of all North Korean government office workers and party organizers are infected with tuberculosis.”[52] No connection was suggested regarding any BW vectors.

Meanwhile, a March 18 North Korean message (source not indicated) concerned a “public opinion project” concerning “the appearance of bacteria weapons.” The project’s progress was “slow” at the battalion unit level. The message reminded its recipient of a “regulation” that required him or her to “report public opinion concerning the appearance of bacteria weapons in a wide sphere.”[53]

A CIA analyst interpreted this intercept to mean that the then-current BW propaganda campaign was “intended to increase both civilian and military feeling in North Korea against the UN.” It’s hard to believe that by March 1952, there weren’t already antagonistic feelings by North Korean soldiers against the UN. It’s just as likely that the sudden increase in germ warfare attack was met with some denial or a failure among the troops to take seriously the bacteriological dangers they faced (something those of us living through the Covid-19 pandemic can likely appreciate).

Another North Korean message, the next day, most likely from the 23rd Brigade in western Korea, reported a bacteria drop in an area occupied by the 18th Regiment, 4th Division. [54]

On March 24, a Chinese Communist unit reported a failure to make the required vaccinations. As a result, a “grave situation” had developed because “friendly troops” (most likely North Koreans) had come down with some unspecified disease.[55]

“The policeman’s report was false”

The next incident described how a North Korean military unit ruled out BW as a cause for the sudden appearance of a group of insects. The cable involved represents a rare instance where the documentary record confirms North Korean efforts to scientifically assess the germ warfare evidence. As such, it constitutes a powerful argument against the hypothesis that North Korea and its allies tried to defraud investigators and construct bogus germ warfare evidence.

On March 25, the 501st Communication Reconnaissance Group intercepted two messages from a North Korean battalion in the Hamhung area. The reports concerned “a civilian police officer [who] discovered an American bacteria bomb.” The report seems to have derived from the coincidence of a UN bombing attack with the sudden appearance of “flies” in the area. A North Korean military sanitation officer was sent to confirm the attack. But the officer reported back that “the policeman’s report was false and that the flies ‘were not caused from the bacterial weapon but from the fertilizers on the place.’”

The CIA analyst describing the COMINT report told his own superiors, “This is the first observed instance in which a Communist unit has investigated and entered a negative report on an alleged American use of BW agents.”[56]

Meanwhile North Korean units on the ground felt inundated by BW attack. On March 30, an “unidentified North Korean regiment” informed its battalions, “the enemy is actively dropping bacterial weapons in general now.” The regiment authorities emphasized, “All units were to report promptly UN biological warfare attacks.”[57]

A day later, on March 31, Radio Pyongyang broadcast an interim report on the germ warfare attacks. North Korea charged that in the nearly 10 weeks between January 20 and March 25, “the US had dropped germ-laden insects on more than 400 occasions.” The broadcast also included “a summary of the detailed preventive measures taken in Pyongyang.”[58]

China had also begun a large-scale health effort called the Patriotic Hygiene Campaign. A “large-scale exhibit on the ‘American war crime of germ warfare’ toured major cities throughout China in the spring of 1952.” Historian Ruth Rogaski stated the exhibit arrived in the city of Tianjin on March 12, and was seen there by nearly 200,000 visitors.

Rogaski wrote, “The Chinese media clearly linked the biological vectors that appeared in 1952 to germ warfare techniques developed by Unit 731.”[59]

At this point in time, the U.S. government was responding in a calculated fashion to Communist charges of biological warfare. The CIA’s Baptism release included a report, dated April 1, 1952, referencing comments from the US embassy in London. The embassy felt “the impact of the Communist BW propaganda campaign in Britain has been negligible to slight,” and “that heavy counterpropaganda from Washington would be unnecessary, but not harmful in effect, as far as the United Kingdom is concerned.”

The UK Foreign Office told Embassy officials, “sources indicate the Communist campaign has had a more substantial effect in the Far East and other areas” than in the West. As a result, the Embassy recommended continuing with the “countercampaign” against the Communist BW charges, “with primary responsibility remaining with Washington.”[60]

The day immediately following the message about the “countercampaign,” a “Top Secret SUEDE” report announced, “Enemy units still reporting BW agents in Korea.” According to this message, a Chinese Communist artillery division had created a five man “health program” committee “in an attempt to check the spread of bacteria.” Additionally, BW “preventive measures were still being pushed actively in North Korea as indicated by continuing reports of unit inoculations.”[61]

There may have been a small gap in U.S. BW attacks during late-April and early May, as a CIA analyst indicated in a May 9 report, or at least Communist public references to such attacks. “During the past few weeks, Communist propaganda has made little reference to specific BW incidents,” the analyst wrote, “although some enemy units reported such attacks as late as mid-April.”

In any case, by May 2 an unspecified North Korean military unit in the Wonsan-Hamhung area reported a nighttime drop of “bacteria weapons at Chongpyong.” A few days later, on May 6 a North Korean coastal security station in northeastern Korea reported “dropped spiders and ants over Songjin city… today.” The intercepted message added that the alleged “drop area” had been isolated and the attack was being investigated by “’the plague prevention work committee.” [62]

The Chinese were also reporting U.S. BW “drops.” A Chinese rocket launcher artillery unit reported on May 6 that “an enemy plane (was observed) dropping propaganda leaflets and germicidal bombs.” The message continued, “the germs were spread over an area 150 meters wide and 600 meters long.” The “42nd Army (in combat in west central Korea) was dispatching personnel to take some specimens.”[63]

The CIA analysts processing the SUEDE intercepts for their intelligence value seemed obsessed with the theme of BW reports as primarily propaganda material. “It is entirely possible that these messages may be used to continue the momentum of the Communist BW propaganda campaign,” one such analyst wrote. “It is entirely possible…” But then again, perhaps it was entirely possible the reports were simply accurate representations of what was occurring in Korea and China at the time.

One U.S. prisoner of war “confession” caught the CIA’s attention in May 1952. The Pyongyang correspondent of a Moscow paper, probably Pravda, reported the capture of an American flyer, Lt. Robert Gilarol. According to a FBIS report dated May 22, Gilarol “admitted his participation in BW following an extensive period of training. Gilarol also admitted, according to Moscow, that he had previously engaged in the campaign to destroy East German crops by disseminating Colorado beetles.”[64]

CIA analysts saw this as “a rare attempt to link up the present BW campaign with the charges [of BW used in East Germany] that were given heavy play in 1950. Neither Pyongyang nor Peking has yet reported this new confession.” Gilarol’s confession was never released, and no one answering the description of Robert Gilarol was ever discovered in records or released from confinement. Searches of public records in the United States do not retrieve even one individual with the surname Gilarol. (A 2005 Ohio State University dissertation [p. 213] by Mark R. Jacobson speculated that the Gilarol reference was really to Marine Captain Robert Gilardi, who was shot down over North Korea in January 1952.)

A June 6, 1952 report summary read, “Communists remain concerned with BW in Korea.” The report described “an unidentified Chinese Communist artillery regiment” telling its “subordinate elements that ‘an investigating committee… is coming to Korea to investigate the releasing of germs and insects by enemy planes and artillery[.] Request that men be found who can verify the releasing of germs…’“[65]

The “investigating committee” was most likely the International Scientific Commission for the Investigation of the Facts Concerning Bacterial Warfare in Korea and China (ISC), organized under the auspices of the World Peace Council, and headed by renowned British scientist Joseph Needham. According to purported Soviet and Chinese documents published by scholars Milton Leitenberg and Kathryn Weathersby, the ISC investigation was to be met by the falsification of contaminated sites and concocted evidence.[66]

It would seem the June 1952 Chinese request to find individuals who could corroborate the germ warfare charges is inconsistent with the charges of Leitenberg and Weathersby. One would think if the CIA had COMINT evidence of the falsification of BW sites, it would have published it with the Baptism release, or otherwise made such evidence public. In the concluding section of this essay, a number of issues regarding conflicting evidence raised by the CIA’s Baptism COMINT documents and Leitenberg and Weathersby’s own purported documentary evidence will be discussed.

On June 13, 1952, the 501st Communication Reconnaissance Group, Korea, intercepted a message from a Chinese artillery regimental commander. The message stated, “Army called my regiment tonight and ordered all chairmen and assistant chairmen of the anti-plague commission to attend the meeting…. the topic of the meeting will be anti-plague project and establishment of anti-plague program for the summer and autumn seasons.” Three days later, the Soviet ambassador to the UN requested a Security Council meeting to discuss the BW charges. He was turned down.[67]

Biological weapons were not the only weapons of mass destruction the Chinese and North Koreans feared. On June 13, a “badly garbled message from an unidentified Chinese Communist unit in Korea” reported that “construction of atom bomb defenses” had begun that very day. Indeed, back on March 30, a Chinese radio broadcast had indicated use of atomic weapons was a “logical step” for the Americans, given their use of biological weapons. On April 4, as well, a Chinese message “indicated that literature about the atom bomb was to be distributed.”[68]

One surprising intercept concerned the capture of Colonel Walter M. Mahurin, who was shot down over North Korea. According to the COMINT report, classified Top Secret CANOE, the capture of this “ranking US airman interests [the] Soviet Ambassador in Korea.

A Soviet ground control intercept on May 16 had “passed a message over its administrative link which stated that ‘Makhurin’ had been captured and that an interrogation had been conducted. The message suggested that ‘Razuvaev’ was present.”

The CIA analyst wrote, “’Makhurin’ is probably US Air Force Colonel Walter M. Mahurin, whose aircraft was shot down by ground fire on 13 May.”

This is the only document in the Baptism release to reference contemporaneously the capture of an officer who would later “confess” to use of biological weapons. It implies Mahrurin was of special interest to the CIA.

“The suggested presence of Soviet Lieutenant General of Aviation, Vladimir Razuvaev, at the interrogation of Colonel Mahurin is another indication of the Soviet Union’s intense interest in the military aspects of the Korean war,” the report explained. “General Razuvaev is the Soviet Ambassador to North Korea and may be the over-all commander of Soviet aircraft participating in the Korean air war.”[69]

A World War II flying ace, Colonel Walker “Bud” Mahurin had been working in the Office of the Secretary of the Air Force at the start of the Korean War. According to his “deposition” to Chinese interrogators, he had visited Ft. Detrick in November 1950, to become better acquainted with the biological warfare research being conducted there. In his autobiography, Honest John, written after the Korean War, Mahurin never denied the visit to Ft. Detrick, though he did deny U.S. use of germ weapons. The book details his friendships with a number of high-ranking military officers and CIA officials.[70]

The appearance of General Razuvaev in this intercept is also interesting, as according to the Leitenberg/Weathersby (L/W) Soviet memos, in April 1953 Gen. Razuvaev told Soviet authorities that Russian, Chinese and North Korean officials helped concoct phony evidence of BW attacks for visiting investigators. Some of the facts the L/W memos propose are falsified by evidence in the COMINT intercepts, including in the letter reportedly written by Razuvaev. Again, this will be examined in the concluding section of this essay.

“Creatures for experiment”

On July 20, according to a Top Secret CANOE intercept, a North Korean artillery battalion commander, “possibly subordinate to the 8th North Korean Division,” informed his superior officers that arsenic had been “put into the well” in the troop area. Apparently, no one had been hurt by this attempted poisoning, but a search was underway for the “culprits.” Meanwhile, other communications intelligence alleged that elsewhere “ten North Korean soldiers died from poisoned food obtained from civilians.”[71]

In mid-August 1952, the Soviet newspaper Pravda republished Chou En-lai’s March 8 statement that “members of American armed forces who fly over Chinese air space using bacteriological weapons will be treated as criminals if captured.” A CIA analyst commented, “Chinese Communist propaganda has given some play to such a threat as: ‘The criminals and their accomplices will be pilloried and severely punished.’”[72]

In his autobiography, Mahurin wrote that Chinese interrogators threatened him with prosecution as a war criminal. Mahurin took this to be an interrogator’s threat, not a governmental policy. In the end, no flyers captured by the North Korean or Chinese seem to have ever been prosecuted as war criminals.

On August 17, the North Korean 21st Brigade notified one of its battalion commanders about a disturbing Chinese Communist intelligence report. The Chinese report, dated August 13, said that the U.S. Army “shipped ‘creatures for experiment’ from a Seoul suburb to Taegu.” That same day “another American Army unit transported five tons of ‘experimental material,’ probably dead rats, from Taegu to an unspecified air base.” The Chinese message cautioned, “all units should be on the watch for the ‘anticipated’ enemy use of bacteriological warfare.”[73]

The CIA analyst’s comment on this intercept was cynical: “the Communist device of passing this type of intelligence to subordinate units has been a sufficient cue for return reports which are then used as ‘proof’ of Communist propaganda charges.”

Of course, it could also be taken at face value. Why would one’s superior officers notify subordinates of an anticipated BW attack if they knew there was no such attack, especially given the importance of allocating military resources in the middle of an all-out war?

One wonders as well, if the North Korean and Chinese BW charges were all about propaganda and untrue in their particulars, why phony BW “proof” had to be solicited in such indirect fashion.

Not one of the CIA’s Baptism release documents complained about the lack of BW reports or evidence. There were also solicitations for witnesses to BW attack. Meanwhile, false BW evidence was turned away, as shown by the March 25 intercept from a North Korean battalion in the Hamhung area, detailed above.

The propaganda and charges surrounding the allegations of U.S. bacterial warfare heated up again in September 1952. First, there was a mini-scandal after a September 3 Tokyo broadcast by Major General William K. Harrison, U.S. Chief Negotiator at the Panmunjom peace talks. Harrison was quoted by “Peiping” radio as “threatening an extension of bacterial warfare against North Korea.” Alan Winnington, a communist correspondent at London’s Daily Worker, reported the quote.

The CIA’s September 5 Daily Korean Bulletin from the CIA’s Office of Current Intelligence admitted the emphasis in Winnington’s article, but said, “the propaganda point was hinged on a five-word quote, ‘disease and dislocation of homes,’ which Harrison may have employed in connection with the devastation created by bombing.”[74]

Contemporary news reports also carried the report of Harrison’s threats to extend “bacterial warfare”, but gave different versions of what Harrison supposedly said.[75]

The ISC Report

On September 13, “Radio Peiping” proclaimed “the US Air Force from 26 August to 11 September flew a total of 740 sorties over Northeast China.” Chinese citizens were said to be “extremely indignant.”[76]

Then, the next day, Radio Peiping announced the International Scientific Commission, investigating charges of bacterial warfare, had completed its work. The report’s release took the CIA by surprise. A September 15 CIA report blandly stated, “The Commission ‘confirmed’ that American armed forces have waged bacteriological warfare against Korea and China. Committee members included scientists from Sweden, France, Italy, the United Kingdom and Brazil, as well as from the USSR.”[77]

The September 23 CIA Daily Korean Bulletin (part of CIA’s FBIS reporting) described yet another Chinese radio broadcast, which presented the ISC report as presenting “incontrovertible evidence” that the UN had engaged in bacteriological warfare. The broadcast said, “the US ‘had the nerve’ to repeat its call for an impartial investigation even after the findings of this unbiased group.”

Meanwhile, the CIA took solace in reports that the presentation of ISC evidence at a press conference held in Stockholm (attended by ISC investigator Dr. Andrea Andree) “was a complete flop.”[78]

A CIA intelligence report dated September 19 declared the “Communist bacteriological warfare campaign [was] being revived.” CIA analysts noted that “Soviet propaganda media” had begun to publicize the ISC’s work. Meanwhile, “Peiping” radio started “to broadcast ‘confessions’ of recently captured American officers and contents of the commission’s report.” The ISC report itself was described as containing “19 chapters and 46 appendices containing 300,000 words, and has been published in English, French, Russian and Chinese.”

The CIA found the ISC report — which I published a few years ago online — to be “among the most serious efforts to date to substantiate the familiar BW charges. The release of this material seems timed to coincide with the Asian Peace Conference….”[79]

One important aspect of the ISC report the CIA did not comment upon was the contention by the commission that the U.S. appeared to have collaborated with the former members of Japan’s BW research and operational command in Unit 731. The CIA may have kept mum because the agreement to give amnesty to Shiro Ishii and his collaborators was secret, and likely only known to those with a “need to know.” The ISC’s insistence on this point may also have been one reason it was met with such hostility by the United States — it threatened to expose the secret U.S. intelligence operation surrounding the Shiro Ishii and the other Japanese BW war criminals.

The ISC dedicated one section of its report to the “relevance” of possible Unit 731 connections. In fact, one member of the commission, Dr. N. N. Zhukov-Verezhnikov of the USSR, had been a member of the Khabarovsk war crimes prosecution. Joseph Needham himself had been in China during the war, working with the Sino-British Science Cooperation Office, helping the allies stay in touch with Chinese scientists. He was well aware of Japan’s biological warfare campaigns in Manchuria.

The ISC report, reportedly written by Needham, remarked:

It should not be forgotten that before the allegations of bacterial warfare in Korea and NE China (Manchuria) began to be made in the early months of 1952, newspaper items had reported two successive visits of Ishii Shiro to South Korea, and he was there again in March. Whether the occupation authorities in Japan had fostered his activities, and whether the American Far Eastern Command was engaged in making use of methods essentially Japanese, were questions which could hardly have been absent from the minds of members of the Commission.[80]

A gap in reports appears at this point in the CIA’s Baptism by Fire release. This could be due to editorial decisions made by CIA, or also to the fact that in the cat-and-mouse game of signals intelligence, the CIA did not have as much information from COMINT during this period. Only a full opening of CIA archives could determine this.

The documentary record picks up again in late November 1952. On November 29, a North Korean military intercept, coded Top Secret CANOE, indicated that “insects” discovered nine days earlier had “been positively identified as unusual.” Even so, there were “no cases of illness” and “prevention measures were being taken.”[81]

Another North Korean military message, dated December 6, described “quantities of insects that carry bacteria” in the North Korean front lines “and attributed their spread to the ‘barbarous United States empire.’” Again, according to the CIA, the North Koreans emphasized the use of public health measures, particularly “against smallpox and typhus, both [according to the CIA] endemic in North Korea.”[82]

By mid-December, the CIA, while describing the distribution of “several publications summarizing ‘evidence’ on the American use of biological warfare… at a BW exhibition currently being held in Vienna,” found “no evidence” of any large-scale revival of BW propaganda as had occurred earlier in the year. [83]

1953

The U.S. biological warfare attacks did not cease in 1953, although the CIA’s Baptism by Fire release did not include any actual COMINT documents pertaining to BW for that year.

Proceeding in a chronological fashion, we find newspaper reports from January 5 detailing Chinese Premier Chou En-lai’s accusation of ongoing U.S. “bacteriological warfare” in Korea and China. Chou also emphasized the actions of “an intensified ‘patriotic health campaign’ on the home front.”[84]

On January 19, the U.S. State Department sent a “circular airgram” to all U.S. embassies in countries that had individuals represented on the ISC investigating committee.[85] As explained in a July 1953 Memorandum of Conversation from a representative of the Psychological Strategy Board, “The effort was to get a refutation of the [ISC] report from a multi-national group of scientists.”[86]

The State Department argued for a “strong counter-offensive” to expose the “big lie” of the Communist BW charges, “and thus undermine Communist credibility on a broad front.” State officials approached the U.K. Foreign Office and asked them to take the lead on this project. The memo described the reaction from British: “They were pleasant but did nothing.” Perhaps this was because, while the CIA found (at least officially) the ISC report to be “a complete fabrication,” “very few of its particular items of scientific ‘evidence’ could be demolished as such.” The U.S. was to have some difficulty finding scientific authorities to back up the campaign against the ISC report.[87]

On February 22, another Communist bombshell revelation took place when the Chinese government released transcripts of “depositions” by “two field-grade American Marine officers attesting to their direction of various phases of the [BW] campaign.” The officers were Col. Frank Schwable and Major Roy Bley, both of the U.S. Marine Corps.

Schwable, as Chief of Staff of the First Marine Air Wing, was the highest-ranking prisoner of war to confess in detail about the U.S. biological warfare campaign in North Korea and China during the Korean War. He described in three “confessions” or depositions how that campaign evolved, what the men undertaking it felt about the campaign, the “effectiveness” of the use of bioweapons, and the security surrounding the covert use of bacteriological weapons. It was a stunning blow.[88]

Of special note is the CIA Far East Survey report, “BW and the Korean War,” dated February 27, 1953, only four days after the Schwable/Bley “confessions.” CIA analysts wrote, “New life has been infused into the quiescent bacteriological warfare campaign…. the new confessions go into considerable detail concerning names, places, dates and policy implementation…. ”

The report argued that there was very little “major new evidence” in the charges of U.S. biological warfare. Instead, Chinese propaganda contained a “rash of peripheral allusions to BW.” As an example, the CIA noted China’s contention that “American support operations in Japan for the BW campaign are an open secret in Tokyo, where corpses of infected persons are used to develop more virulent strains.”[89]

Oddly, the report included a summary of differences between the Schwable and Bley confessions and those of lower-ranking officers Lt. F. B. O’Neal and Lt. Paul Kniss, which were reproduced in the ISC report.[90]

According to the CIA, “Some of the difference may be laid to the basic dissimilarities between actions at the working level and at levels concerned primarily with giving and interpreting orders. Since Schwable and Bley were allegedly concerned with the implementation of directives from higher authority but not with the actual operations of dissemination, the extent to which they could discuss operations in precise detail is probably limited; conversely, since Kniss and O’Neal were not privy to the high-policy decisions which put the operations into effect, their confessions might necessarily be limited to the recital of minute details concerning the actual operation.”

This was an argument for the authenticity of the flyers’ depositions. CIA seems to have realized this and concluded this was part of the Communists’ construction of an “illusion of truth.” CIA also felt that the Schwable and Bley documents lacked “other elements that would have logically appeared at the command level.”[91] No examples of such “other elements” were given.

The entire February 27, 1953 report is worth further analysis for an example of how the CIA was spinning the news out of Peking and Pyongyang in real time regarding the flyers’ “confessions” and other revelations from the ISC report. There remains one other important aspect to this report.

Leitenberg and Weathersby Documents

In a section sub-headed “North Korea,” the CIA stated, “Pyongyang’s own contribution to the upsurge in atrocity charges appears in the form of a ‘Fifth Communique on Atrocities Committed by the American Aggressors and the Syngman Rhee Gang.’ The “Communique” was rebroadcast by Moscow and Peking and included charges regarding “U.S. atrocities,” including “destruction of urban and rural areas through bombing; use of weapons for wholesale massacre; i.e., poison gas and BW; and the destruction of cultural and social installations, again, through wanton bombing.”

The CIA report said, “a long compilation of alleged incidents is used to document each charge.” North Korea is described as calling for a “people’s trial” for the “criminals” involved.[92]

A few weeks prior to this, in mid-February, a CIA “open source” report noted a North Korean announcement of a new anti-epidemic campaign. The North Korean government specifically referenced “the threat raised by enemy use of BW….”[93]

What makes these February CIA reports noteworthy is that documents accepted as authentic in the West allege that North Korea had soured on the attempt to falsely label the U.S. as using BW by January 1953, and stopped issuing propaganda on the issue.

The scholarly work of Milton Leitenberg and Kathryn Weathersby, published by the Wilson Center, refers to a purported April 18, 1953 letter from the Soviet Ambassador to North Korea, Vladimir N. Razuvaev, to then-Soviet security chief L.P. Beria.

“From January 1953 on,” the letter from Razuvaev states, “the publication of materials about the Americans’ use of bacteriological weapons ceased in the DPRK. In February 1953 the Chinese again appealed to the Koreans regarding the question of unmasking the Americans in bacteriological war. The Koreans did not accept this proposal.”[94]

This entire story is false, but it’s unlikely anyone in the West knew that until the publication of the links and documents in this article.

We must assume that Razuvaev either lied for some reason in his letter to Beria, or that he never wrote the letter involved, since it is difficult to believe that a Soviet ambassador and advisor so close to the North Korean regime — we already have seen that he likely was involved in the interrogation of downed flyer Walker Mahurin in North Korea — wouldn’t know what stance North Korea was taking in regards to charges of U.S. germ warfare. The contradiction between what some of Leitenberg/Weathersby documents state and what has been revealed in declassified U.S. intelligence documents requires further examination.

There is nothing in the COMINT Daily Report files from January 1953 on, as released, that concerns charges or details of the reported bacterial warfare attacks from the United States. There were ongoing press reports, however. For instance, a United Press story on March 25, 1953, reported China’s charge that “American planes made 60 germ warfare missions over North Korea between January and mid-March [1953].”[95]

The issue also continued to be discussed in CIA FBIS intelligence reports throughout 1953. These reports were based on “open source” material rather than top secret radio or telephone intercepts. This material makes clear that Soviet, North Korean and Chinese charges of U.S. use of germ or bacteriological weapons continued even after the armistice of July 1953.

They also continued after documents released by Milton Leitenberg claimed they stopped. Besides the purported Soviet documents mentioned above, in March 2016, Leitenberg released an English language translation of a supposed memoir by Wu Zhili, “Director of the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army Health Division during the Korean War.”[96]

In Wu’s memoir, the Chinese government is taken aback when a May 2, 1953 cable arrives from the Soviet Union explaining that the BW propaganda campaign was not credible and that a retraction was in order. Wu claims that Premier Chou En-lai promptly ordered a retraction of the germ warfare charges, and subsequently “China did not raise the matter again.”

Leitenberg has stated that the latter statement was not true, and cited a 1988 Chinese history of the Korean War as an example of ongoing Chinese reference to the Korean War U.S. BW campaign. But actually, not only was there never was a retraction by China, but continued complaints of U.S. use of BW continued throughout 1953, for many months after the Wu document claimed they ended.

An entire critique of the various Leitenberg documents awaits a full evaluation, though some critics have already thrown them into doubt.[97]Nevertheless, the selections in this essay from the Baptism CIA release are also very telling, as they falsify some of the claims made in the Leitenberg documents.

One additional Baptism document in this regard is the November 19, 1953 CIA FBIS report from its Far East Survey bureau. The section on Korea begins, “Peking Opens New BW Barrage.” The new campaign began on November 11, when China released depositions by 19 additional U.S. servicemen implicated in the germ warfare campaign.

“Widespread broadcasting of the new confessions is being accompanied by vehement support propaganda which largely reviews past evidence, reiterates old accusations about the plans and purposes of the U.S. action, and asserts that these new revelations represent further irrefutable proof against current American denials,” the report stated. “Pyongyang also gave heavy play to the new confessions,” the CIA document said.

How is it possible that Wu Zhili, who stated China’s propaganda about US germ warfare ended in May 1953, and who even mentions the statements of captured U.S. flyers in his “memoir,” did not know of the November 1953 publicity campaign surrounding the release of the 19 flyers’ BW depositions? One imagines it would be to the benefit of the U.S. government that historical memory pertaining to the flyers’ statements be forgotten. Indeed, the flyers’ statements are extremely difficult to find in any U.S. library. However, recently, some of these “confessions” have been released online.[98]

These short excerpts from the documentary record — and they can be corroborated by contemporary press accounts[99] — show the celebrated Leitenberg documents meant to debunk Communist claims of U.S. use of biological weapons during the Korean War have serious inconsistencies when placed in comparison with the historical record, as that record is slowly being revealed with the release of previously classified material.

Summary

The COMINT cables and other intelligence reports released by the CIA in 2013 under the heading “Baptism by Fire” provide a real contribution to our understanding of the North Korean and Chinese experience of the war, as well as U.S. communications intelligence efforts. In particular, they provide a rare window into North Korean and Chinese military reactions and responses to what they said was a biological warfare attack, whose air component began in January 1952 and continued almost up to the armistice in July 1953.

U.S. Cold War scholars and many journalists have decided that the case is closed and that the Communist side in the Korean War faked evidence of germ warfare, and fooled international investigators, including a world-renowned British scientist. The scholars have provided documents from China and the Soviet Union that, though they are of dubious provenance, the scholars maintain are authentic and conclusive about the germ warfare “hoax.”

In this matter, scholars such as Milton Leitenberg, Kathryn Weathersby, and others are in agreement with the U.S. government’s position, which is that the United States did not undertake biological warfare during the Korean War. Some of the contemporaneous U.S. responses at the time of the Korean War cannot be upheld as trustworthy. For instance, U.S. claims that the Japanese did not conduct germ warfare against China, or that any agreement was ever made with Shiro Ishii and the scientists of Unit 731, or that the Soviet war crimes trials against Unit 731 personnel at Khabarovsk in late 1949 were mere show trials, were proven false. Indeed, the U.S. government consciously lied.[100]

Historian Ruth Rogaski, who wrote on China’s massive public health response during the Korean War, took a more nuanced approach in a 2002 article. She concluded that “rather than seeing local germ warfare reports as products of dissembling officials or a deceitful central government policy, it is more instructive to read them as testaments to the fears, uncertainties, and convictions of a nation that had been in a state of war for decades.”[101]

In 2020, a new book by Nicholson Baker concluded the germ warfare campaign against North Korea and China was indeed a covert operation, but that after perhaps some initial bacteriological attack, the bulk of the insect and animal drops were uninfected, and were actually meant as a form of psychological warfare, terrorizing the population with the false belief that they were under bacterial assault.[102]

The problem with all these other hypotheses is that they must ignore the evidence of actual biological attack rendered in the ISC report, which included the reproduction of medical evidence and interviews with many eyewitnesses, as well as other evidence, including other eyewitness and the testimonies of the U.S. captured airmen.

Importantly, a selection of COMINT cables and other previously secret and “confidential” intelligence reports from the Korean War now are available to serve as historical evidence. The information from the COMINT data corroborates charges that North Korea and China were under bacteriological attack in 1952, and disconfirms some of the evidence offered suggesting the attacks were really a “hoax” or an exaggerated response to presumed, but more innocent attack.

This essay is only a preliminary examination of a subset of the COMINT reports that dealt with BW subject matter. It is not a full history of the Korean War BW controversy. Even so, other scholars will have much to consider when examining this new evidence.

Because the CIA itself curated the selection of documents, one cannot say with assurance how much evidence can be derived from a full release of all records. Many of the documents are still, decades after they were first generated, redacted significantly. Scholars and the public must call for a full release of all records, the better to understand a vital episode in U.S. and world history.

It might also be possible, years after the fact, and in a world still rent by the divisions of the Korean War, to settle once and for all the charges of germ warfare, and render some justice to those who suffered so cruelly the effects of all-out war on the Korean peninsula and northeastern China in the early 1950s.

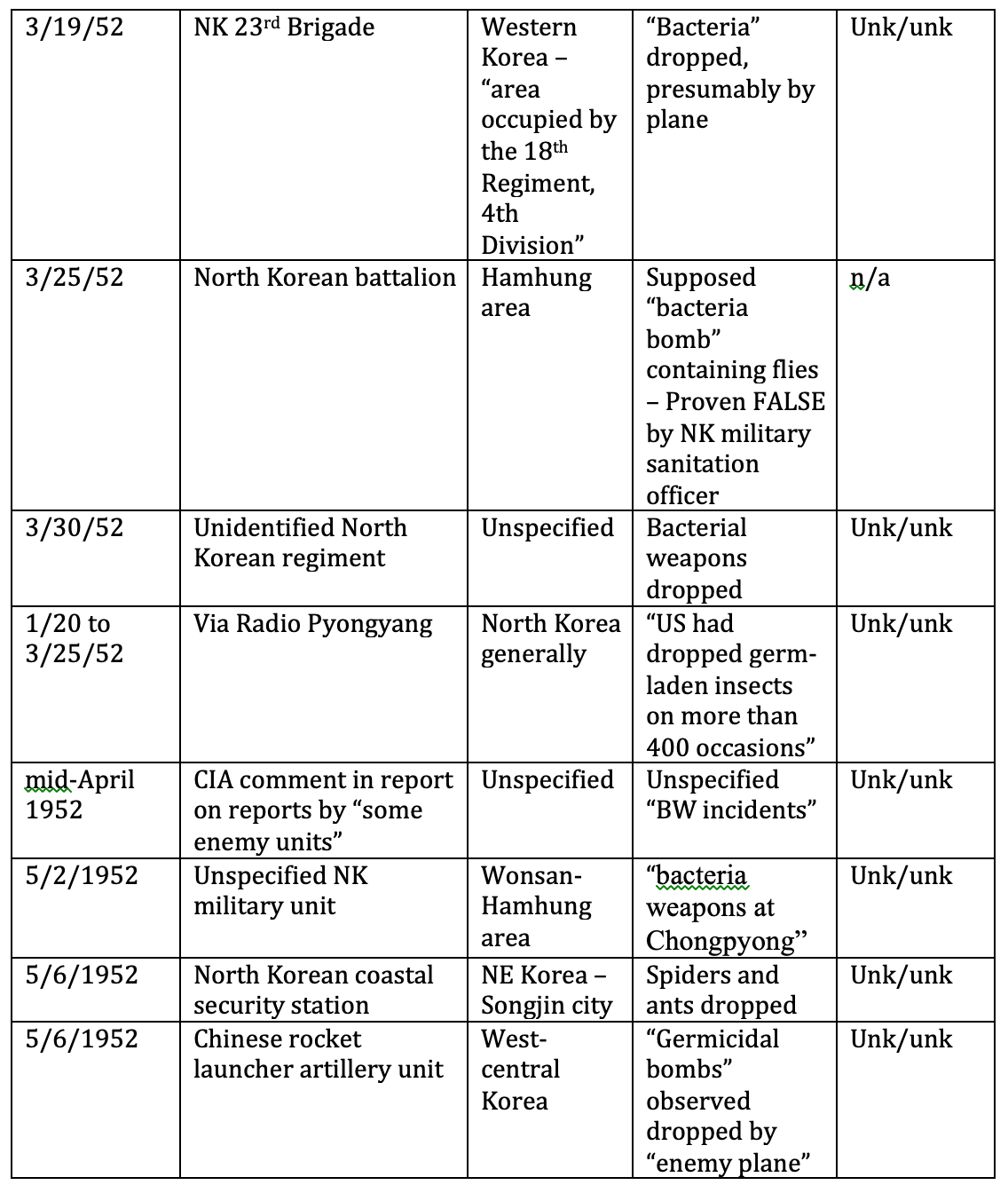

Table 1 — Attacks documented in CIA Release of 1952 Top Secret SUEDE/CANOE COMINT documents

It is worth noting that the amount of injuries or deaths is barely reported here. As the General Sams episode related in the main body of this paper suggests, identifying the BW casualties was a highly classified matter. The ISC report also refused to discuss casualty numbers, which would have added to U.S. intelligence on the effects of their germ war, as the report authors saw it. Even so, the ISC report does report some deaths from cases of plague and cholera that were investigated.

COMINT and Intelligence Files Pertaining to Allegations of U.S. Germ Warfare Attack, 1951–1953 (from CIA’s Baptism by Fire collection)

Click here if you cannot see or download the COMINT files.

Endnotes

[1] The Korean War COMINT code words SUEDE and CANOE were preceded by the code words COPSE (in use at time the war started, and until July 1950) and ACORN (August 1950 — June 1951). No COPSE or ACORN documents that mentioned BW were included in the “Baptism by Fire” release. According to one researcher, “These code words signified to the initiated the presence of Comint and helped control access to Comint material. Documents carrying the code words were only issued to people with Comint security clearances and were stored more securely than government papers merely classified as ‘top secret’ or ‘secret.’” — David Easter, “Code Words, Euphemisms and What They Can Tell Us About Cold War Anglo-American Communications Intelligence,” Intelligence and National Security, Vol. 27, №6, pp. 875–895, published online July 18, 2012. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2012.699288 (accessed September 11, 2020).

[2] See Nicholson Baker, Baseless: My Search for Secrets in the Ruins of the Freedom of Information Act, Penguin Press, NY, 2020, pp. 240–243, 249, 292, 365, 415–417, 423 433. All in all, Baker references one-half dozen of the SUEDE COMINT reports, and none of the CANOE reports.

[3] Milton Leitenberg, “China’s False Allegations of the Use of Biological Weapons by the United States during the Korean War,” Cold War International History Project, Working Paper #78, Wilson Center, March 2016, URL: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/publication/cwihp_wp_78_china_false_bw_allegations_korean_war_march_16.pdf (accessed August 31, 2020).

[4] See Edward W. Proctor, “The History of SIGINT in the Central Intelligence Agency, 1947–1970, Vol. 1,” DCI Historical Series, October 1971, URL: https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB506/docs/ciasignals_16.pdf; Thomas H. Johnson, “American Cryptology During the Korean War,” Studies in Intelligence, Vol. 45, № 3, 2001. URL: https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/2001-01-01.pdf; David A. Hatch with Robert Louis Benson, “The SIGINT Background,” National Security Agency online document, June 2000, URL: https://www.nsa.gov/News-Features/Declassified-Documents/Korean-War/Sigint-BG/; P.K. Rose, “Two Strategic Intelligence Mistakes in Korea, 1950,” Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency: 2001, 5, URL: https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/csi-studies/studies/fall_winter_2001/article06.html; and Thomas J. Patton, “Commentary on ‘Two Strategic Intelligence Mistakes in Korea, 1950’: A Personal Perspective,” Studies in Intelligence, Volume 46, Number 3, 2002, URL: https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/csi-studies/studies/vol46no3/article11.html (all sources in this note accessed on September 9, 2020).

[5] Thomas J. Patton, ibid.

[6] See Thomas H. Johnson, footnote 4

[7] David A. Hatch with Robert Louis Benson, “The SIGINT Background,” National Security Agency online document, June 2000, URL: https://www.nsa.gov/News-Features/Declassified-Documents/Korean-War/Sigint-BG/

[8] See Materials on the Trial of Former Servicemen of the Japanese Army Charged with Manufacturing and Employing Bacteriological Weapons, Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1950, URL: https://books.google.com/books?id=ARojAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

[9] Jing Bao-Nie, “The West’s Dismissal of the Khabarovsk Trial as ‘Communist Propaganda’: Ideology, evidence and international bioethics,” Journal of Bioethical Inquiry 1, pp. 32–42 (2004). URL: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02448905 (accessed September 12, 2020.

[10] Jeffrey Kaye, “Department of Justice Official Releases Letter Admitting U.S. Amnesty of Japan’s Unit 731 War Criminals,” May 14, 2017, Medium.com, URL: https://medium.com/@jeff_kaye/department-of-justice-official-releases-letter-admitting-u-s-amnesty-of-unit-731-war-criminals-9b7da41d8982 (accessed September 12, 2020). Very little has been published on the casualty rate in China from Japanese BW campaigns. For figures from Chinese sources, see James Yin, The Rape of Biological Warfare: Japanese Carnage in Asia During World War II, Northpole Light Publishing House, San Francisco, CA, 2002.