9/11 attacks: Restoring the US myth of invincibility through sexual violence

September 11 2001 was, to a large extent, an assault of the image. The image of the planes hitting the Twin Towers exceeded the event itself; for social theorist Jean Baudrillard, the symbolic collapse of the World Trade Center was at stake, its physical collapse only a side effect.

The image summarised the centrality of New York and the World Trade Center to the “pre-9/11 world”, and ominously anticipated the US wars on Afghanistan and Iraq. For many Americans, this image triggered a novel sense of vulnerability. For many American “patriots”, this justified the violence to come.

For many of us who live outside the US, the set of images that permanently left its mark on our psyche and our relationship with the American empire came a few years later, in 2004, when the photographs depicting the torture and degradation suffered by the prisoners at Abu Ghraib were leaked. Although the photographs were not intended for circulation, they indexed and embodied how, to restore its own sense of invulnerability, the US war machine needed to render the "others" of the empire vulnerable, victimised and violable.

The Abu Ghraib images embodied the gendered and sexual typification of dominant power relations: colonisation is captured in the image of sexual violence

The Abu Ghraib images embodied the gendered and sexual typification of dominant power relations: colonisation is captured in the image of sexual violence, of simulated and real rape, and of coerced sexual bondage; the coloniser, even when female, occupies the virile position, and the colonised, even when male, occupies the receptive and penetrated position that is stereotypically coded as feminine. In other words, it captures the ways whereby colonial, political and military dominance has typically been imagined and narrated.

It is particularly in the figure of the female prison guard, masculinised through her dominance over the feminised male prisoners, that the sexual coding of imperial force relations is evident. "By feminising the enemy as an object of penetration,” Joseph Massad argues, “American imperial military culture supermasculinises not only its own male soldiers, but also its female soldiers who can partake in the feminisation of Iraqi men.”

The Iraqi prisoner, on the other hand, and through him entire Arab and Muslim populations, is forced to occupy the position of degradation, which the misogynist paradigms of empire has feminised. The racially and sexually perverse figure that emerges from the semiotics of the "war on terror" is captured by the figure of the “Monster, Terrorist, Fag” which Jasbir Puar constructs in the course of her thought-provoking analysis of the war on terror.

The empire’s production of corporealities and sexualities that are proper and respectable by virtue of their whiteness, vis-a-vis ones that are improper and abject by virtue of their deviation from whiteness and/or white norms, crystallises in the Abu Ghraib images; according to Puar: “Not only is the Muslim body constructed as pathologically sexually deviant and as potentially homosexual, and thus read as a particularised object for torture, but the torture itself is constituted on the body as such… the body informs the torture, but the torture also forms the body.”

The restitution of the white, American, nationalist body through the production of its other as perverse and violable presents a common representational strategy of the war on terror, a strategy that was both anchored in and further informed by the physical violence of America’s imperial wars. As the victims of the war on terror were, in Massad’s words, “posited by American super-masculine fighter-bomber pilots as women and feminised men to be penetrated by the missiles and bombs ejected from American warplanes”, American and European cinematic representations were playing their role in the semiosis of the war on terror, producing racially and sexually perverse (Arab and non-Arab) terrorist bodies and populations.

A world dismembered

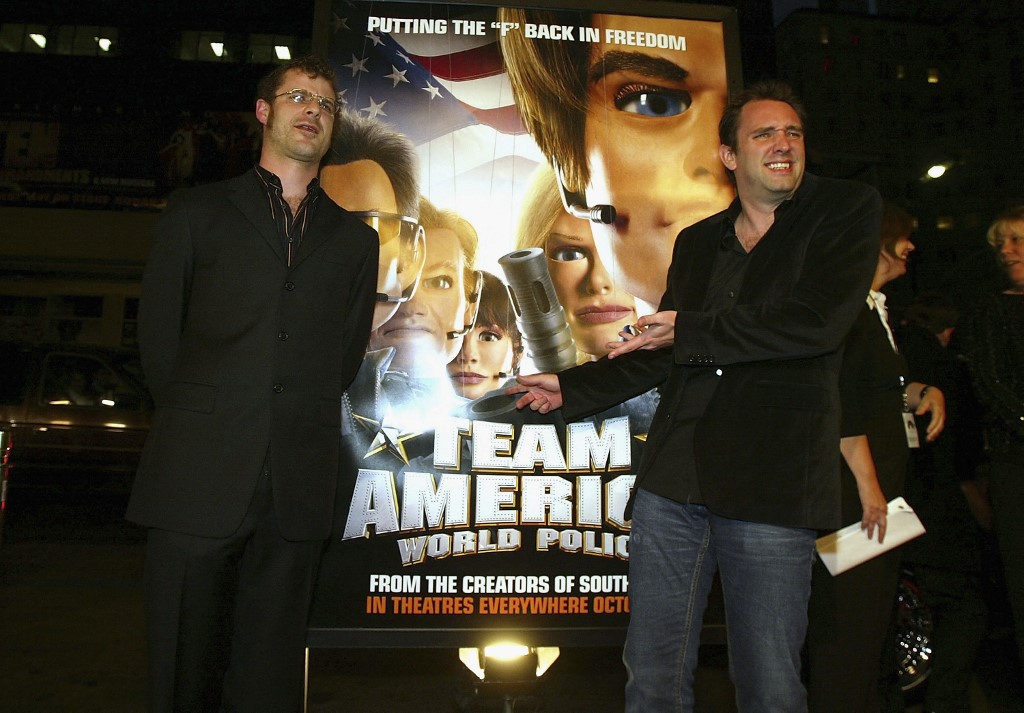

Team America: World Police (2004) was one of Hollywood’s contributions to the war on terror; it was one that at worst glamourised, and at best endeared, American jingoism and racism under the guise of satire. The plot revolves around a team of US special forces (portrayed by puppets), whose arrogance, along with the collateral damage this arrogance causes (including the destruction of Paris and Cairo), is ultimately excused as it is weaponised to keep the world safe from terrorists and their sponsors.

The destruction of Paris in the crossfire between terrorists and Team America in the first few minutes of the film registers the fate reserved for western capitals that do not promptly fall in line with America’s war on terror - France being a vocal critic of the 2003 invasion of Iraq. The destruction of the Louvre by a stray American missile courts the jingoist’s hostility towards global culture (whereas the Eiffel Tower, American cinema’s favourite simulacrum for an American-friendly Paris that opens its arms to tourists without overwhelming them with culture, remains intact).

The destruction of Cairo - though also collateral - is depicted more meticulously and vindictively: various ancient Egyptian monuments (including ones not really located in Cairo) are demolished while burning shrapnel and debris fall over the heads of Cairene crowds. While American viewers are expected, perhaps, to laugh at or with their rogue heroes at the carnage they leave behind, and at the crass visual expression of American exceptionalism that gives itself the right to symbolically and semiotically destroy the rest of the world, non-American audiences are left to wonder: why do they hate us?

Taking into account how 9/11 was experienced as the unprecedented violation of the American national body - in addition to Judith Butler’s note on how the American response to this experience was to refabricate the myth of invincibility through enacting global violence instead of commiserating in universal vulnerability - these scenes emerge as attempts to restore, on the level of the image, the integrity of the American body through stressing the violability of the international (terrorist and bystander) body. This extends to the bodies of the individual terrorists, terror sponsors, and terrorist sympathisers whom the film sadistically dismembers.

While American viewers are expected to laugh at or with their rogue heroes at the carnage they leave behind… non-American audiences are left to wonder: why do they hate us?

From the beginning of the film, terrorism is signaled through the perverse corporeality that is stereotypically coded in American cinema as Muslim and/or Arab: turbaned, in ambiguously South Asian/Arab garbs, dark skinned, with thick eyebrows and copious beards, always threateningly frowning, etc. The appearance of such features is enough for the screen to darken, music to change, children to intuitively recognise the terrorist threat, and for Team America to start targeting these perverse terrorist bodies with their bullets and explosives.

During the film’s first scene, the terrorists eventually turn out to be carrying a “weapon of mass destruction” in the form of a handbag. The terrorist body and its lethal appendage form an assemblage in the sense suggested by Puar, yet the terror is readily inscribed on the body. “For [Judith] Butler,” Puar notes, “the visible black body [and by extension the visibly terroristic brown body, as Puar shows and as the movie illustrates] is a priori signified as threatening."

Puar concludes: “Unmoored emotions such as fear slides amid bodies, getting stuck on them.”

This construing of the other as a threat engenders various forms of preemptive violence, congruent with the violence enacted in the film, on the threatening terrorist bodies, which is triggered by their morphological perversity but serves to preempt the detonation of their explosive handbag. The violence not only neutralises the terrorist bodies, it completely dismembers them.

This fate extends to those who refused or failed to align themselves with the American military establishment - misrepresented in the movie as terror sympathisers and/or apologists: UN diplomat Hans Blix, in a supposedly comical scene, is eaten by sharks; American liberal filmmaker Michael Moore blows himself up; other US celebrities who opposed the war are gruesomely blown up by bullets or bombs, with scenes showing their heads flying off their bodies, their entrails protruding from their groins, or their bodies completely shattered.

Terrorist as sexual monster

A heavy-handed homophobic language subtends the production of these fragmented bodies: the terrorists are called homophobic epithets, by Team America but also by songs that act as narrative ballads. One of the leaders of the terrorists (a Cairene Chechen warlord) repeatedly, if unwittingly, makes double-entendres that implicate him as a homosexual. Criticism of America’s reckless violence as it polices the world is voiced by an imaginary association called “Film Actors’ Guild” or “FAG” for short (of which the members are gruesomely killed in the manner described above). The homophobic epithet serves to exile the unpatriotic voices beyond the realm of accepted (homo)sexuality before they are also dismembered towards the end of the film.

Not all homosexual practices are equally maligned, however. In one scene, the leader of Team America insists that one of his discredited men should perform oral sex on him in order to regain his trust. He insists that this is not about sex but about proving his commitment to the team and its cause. Captured into the orbit of American patriotism, jingoism and war on other people, this homosexuality escapes the homophobic discourse that produces terrorist perverts and liberal FAGs. The comedy remains homophobic, though it allows for American exceptionalism to expand and include forms of patriotic white homosexuality, or homonationalism, to use the term coined by Puar.

The sexual monster thus emerges in opposition to the white, patriotic, hetero and homonationalist subject. Homosexuality, according to Puar, “must be displaced from whiteness in order to retain its demonic capacity to perversely racialise bodies”. Skin colour and political allegiance, rather than sexual practice, produce the sexual pervert.

This phenomenon (“the pathologisation of the terrorist bodies that is surfacing in popular culture” as per Puar’s formulation) is not exclusive to American cinema. The terrorist as the sexual monster returns in European cinematic representations of terrorism, including ones that masquerade as art house and radical chic.

Maligning tropes

In Olivier Assayas’s 2010 pan-European production, Carlos, the eponymous international terrorist appears to embody various attributes of the sexual monster. This is most evident in a ridiculous (supposedly sexually suggestive?) scene where Carlos rubs his weapons against the body of one of his female comrades, before explaining to her “weapons are an extension of my body”. The referent for this “terrorist assemblage” comprising the monstrous terrorist body and its lethal appendages is indeed Arab: Carlos quickly explains that this is a lesson he learned during his training in the Bekaa Valley.

Cinematic images coalesce with the rhetoric, semiology and culture of the war on terror to produce the racially and sexually perverse (Arab and pro-Arab) terrorist

The terrorist monster, whose corporeality is disfigured by racial markers (some sartorial, some inscribed on the skin) and lethal appendages thus takes his place next to the more familiar figures of visual representations of terrorism and of racist American cinema more broadly: foreign (ambiguously Arab, though sometimes South Asian, Russian, Eastern European, and/or Latin American) accents; the polygamous and misogynist Muslim (or, in the case of Carlos, about-to-turn-Muslim) male; the hysterical and licentious woman making herself available for the perverse desires and the equally perverse political designs of the male terrorist and providing the feminine referent for the hysteria of the terrorist organisation. (In Carlos, the female entourage surrounding the eponymous terrorist served this representational strategy, in The Baader Meinhof Complex, a 2008 German film retrospectively examining Europe’s experience with far-left terrorism, German militants Gudrun Ensslin and Ulrike Meinhof, despite their prolific theoretical contributions, were reduced to hysterics to articulate the supposed hysteria of their organisation, the Red Army Faction.)

Cinematic images coalesce with the rhetoric, semiology and culture of the war on terror to produce the racially and sexually perverse (Arab and pro-Arab) terrorist. These maligning tropes raise the stakes beyond the production of white normativities and terrorist perversities (often Arab, but occasionally European contaminated by the Arab they ally themselves with) to engendering violence against discursive and geographic localities and the populations that inhabit them.

Some of this violence takes place purely on the level of the image, like the destruction of Paris and Cairo in Team America. But often the image is constituted from the real rubble of cities like Kabul and Baghdad, and real piled-up, humiliated, tortured, raped, and/or killed bodies of populations that do not fit the normative standards of the American empire.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home