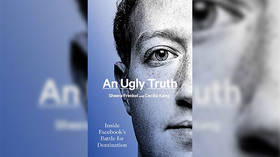

New book ‘An Ugly Truth’ propagates the widespread prejudice that Facebook users are gullible children in need of protection

is a writer, speaker and consultant on innovation and technology, was most recently a Director at PriceWaterhouseCoopers, where he set up and led their crowdsourced innovation service. Follow him on Twitter @Norm_Lewis

Whatever your political persuasion, it is difficult not to acknowledge how remarkable the Facebook phenomenon truly is.

For example, during the Covid pandemic, 2.6 billion people were using one of Facebook’s three apps every single day. Having faced numerous lawsuits – which New York Times tech journalists Sheera Frenkel and Cecilia Kang point out has been the “strongest government offensive against a company since the breakup of AT&T in 1984” – Facebook has defied the odds and continued to grow and thrive. Indeed, the day a federal judge dismissed the suits, Facebook’s stock rose 4%, pushing its market capitalisation above $1 trillion for the first time.

If the book’s authors are to be believed, Facebook has achieved this through the duplicitous use and manipulation of personal data, deliberate obfuscation and criminal inaction.

While the book details many instances of such behaviour, this does not explain Facebook’s seemingly unstoppable momentum.

In reality, no one is holding a gun to the billions of Facebook users’ heads, forcing them to share their personal data, likes and dislikes. Despite all the media claims of the dangers of fake news, the misinformation and conspiracy theories and data harvesting for advertisers that drives Facebook’s profitability, people keep coming back.

It is this phenomenon that even Facebook’s founder Mark Zuckerberg and all of Facebook’s evangelists and critics still do not understand.

ALSO ON RT.COMExposing public figures’ offensive social media posts from the past isn’t about justice. It’s about envy.It is a technologically deterministic worldview which believes that Facebook’s algorithms and Cheryl Sandberg’s model of behavioural advertising account for all its success. What is ugly about this, according to the authors, is that the determining platform is “built upon a fundamental, possibly irreconcilable dichotomy: its purported mission to advance society by connecting people while also profiting off them. It is Facebook’s dilemma and its ugly truth.”

The idea that Facebook is making a profit from human data may come as a shock to tech journalists. For those of us who inhabit the real world, Facebook is no different to hundreds of capitalist monopolies that profit from human exploitation.

The form may be different. The result is the same. Facebook treats human data as financial instruments to be bartered in markets like orange juice or copper futures. Privacy violations are just the cost of doing business.

As the authors point out, after the joint Senate Committee on Commerce and Senate Committee on the Judiciary hearing in which Zuckerberg was forced to appear, shares of Facebook made their biggest daily gain in nearly two years, closing up 4.5%. Over 10 hours of testimony and 600 questions, Zuckerberg had added $3 billion to his wealth. Even a $5 billion fine imposed by the Federal Trade Commission after the Cambridge Analytica scandal resulted in Facebook’s stock rising after investors were pleased to have the case resolved.

The book’s title, and thus its focus, is drawn from an internal posting written by one of Facebook’s longest-tenured executives, Andrew Bosworth, which he called “The Ugly.” In the 2016 memo, which he says he wrote to provoke debate, he explained that Facebook cares more about adding users than anything else. “The ugly truth is that we believe in connecting people so deeply that anything that allows us to connect more people more often is de facto good,” he wrote. “That can be bad if they make it negative. Maybe it costs a life by exposing someone to bullies. Maybe someone dies in a terrorist attack coordinated on our tools. And still we connect people.”

This is an important insight. Again, not because it reveals that Facebook and its investors are rapacious capitalists, but because it exposes how the social network is driven by forces beyond its control, which it struggles with internally and externally.

ALSO ON RT.COMAnother Pr**k in the Wall? Roger Waters chews out Mark Zuckerberg for wanting to use Pink Floyd protest song in Instagram ad filmThe book gives some fascinating insights into the internal drama and decision-making at Facebook. It often shows the dysfunction of its top ranks, revealing tensions between Zuckerberg and Sandberg. Again, there is nothing exceptional about this in an enterprise of this size and nature.

But what is truly revealing is the internal work culture; how employees who report to the top executives are afraid and unwilling to bring the leaders bad news. The pressure to grow Facebook’s audience and revenue are relentless. Anything that slows that down is shunned.

Internally, Facebook is a surveillance state: the authors describe how Sonya Ahuja, a former engineer, heads up an internal investigations unit that hunts down everything from harassment and discrimination complaints to leakers and whistleblowers. This ‘Stasi’ unit has an eagle’s-eye view into the daily workings of all Facebook employees, with access to all communications. Every move of a mouse and every tap of a key is recorded and can be searched by Ahuja and her team.

Facebook demands that many employees sign an additional nondisclosure agreement. It is notorious for taking an exceptionally strict line with employees. And why? Because of the need to meet market expectations about growth and usage. Facebook lives or dies by that need.

While the pursuit of profit makes for a ruthless internal and external culture, no one is holding a gun to the heads of Facebook’s employees, forcing them to work each day. They choose to be there for numerous reasons: financial, career opportunities, the possibility of real innovation, or indeed, even perhaps by the ideological appeal of connecting the world’s population.

What the book exposes, above all else, is how so much of the commentary about Facebook is driven by myths and Silicon Valley Kool-Aid.

The authors reveal that while Facebook would like the world to think it is a black box, that there are systems and algorithms driving decisions, in actuality, this is far from reality. When it came to the curation of news for which Facebook was slammed by President Trump and the Republican Party for bias, some employees were making critical decisions about content, not algorithms, and without any oversight.

This is fascinating stuff. It gives an insight into how hand-to-mouth and day-to-day life is inside the advertising machine, which explains why change only comes in response to external pressure, whether in the form of regulatory inquiry or an explosive media story.

‘An Ugly Truth’ could have been a fascinating insight into how Big Tech operates, how technology interacts with human society and how each is influenced in turn as they evolve.

Instead, we have a morality play about profit which obscures a real ugly truth: namely, that all sides in the debate hold extremely odious views about humanity as a whole. On one side are the technological determinists who believe that technology forces human beings to act regardless of human will or autonomy.

ALSO ON RT.COMFacebook’s desire for you to report your friends is the latest alarming step in its bid to take over the worldOn the other hand, we have the critics who see ordinary people as vulnerable children, narcissistic, gullible and easily manipulated. It is a degraded view of humanity, which of course, serves a technocratic agenda demanding more intervention, the regulation of free speech, and rule by those felt to be above the misinformed masses, the experts.

Bosworth is right. Connecting people across the world and in real-time is de facto good. As a communications platform, Facebook is a remarkable human achievement, unprecedented in human history.

Of course, Facebook yields enormous power as their banning of President Trump from their platform attests to. It is now, de facto, one of the gatekeepers of the new public square. As it comes under increased pressure from critics like these authors, Facebook has shown itself to be infinitely pragmatic and willing to forsake its principles – all in the name of protecting its profits. This book will only add to that dynamic.

Connecting three billion people and potentially creating a super-computer the likes of which has never been seen before should be applauded and encouraged, not demonised. Facebook has unleashed an unstoppable process. The future will be determined by the billions of people using it, not regulators in Washington or critics in New York or evangelists in Silicon Valley. That’s the beautiful truth about the Facebook phenomenon.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home