Part II – Western Capital’s Long Chinese Mission: From Opium to COVID Vaccine Credentials

By Raul Diego

WASHINGTON — In “The Disarticulation of Pandemic War Propaganda,” a transparent attempt to frame China as the instigator of worldwide lockdown policies was revealed to be the work of a group of self-styled libertarian-minded individuals. Their links to the UK, the United States, and Canadian governments tie a neat Pentagon-size bow around ongoing efforts to demonize the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

The ‘specter of communism,’ which worked well during the twentieth century as an intimidation factor to break down protectionist policies and impose oppressive debt regimes, is now being revived to resuscitate an economic paradigm that is long past its sell-date.

Having nearly exhausted the bounty of the natural world, global capital is now forced to create new markets out of thin air to continue its relentless march toward oblivion. Abstractions like “intellectual property” will still need to rely on the extraction of tangible goods like minerals and – as it has from the beginning – the exploitation of human life.

In this second part of “Dragon’s Blood Harvest at the Dawn of Human Capital Markets,” we will examine the virtually unbroken history between American power-brokers and the highest echelons of power in China — a history that harkens back to the earliest days of capitalism, slavery, and the opium trade and that established a permanent pipeline for the transfer of technology and medical and scientific knowledge to China through Western philanthropic organizations dating back to the early nineteenth century.

Towards the second half of the twentieth century, even as China’s post-war communist revolution seemed to diminish Western influence in the country, these early links to American academic, scientific, and banking circles were never completely severed. By 1971, diplomatic relations between the U.S. and Mao’s China were officially restored, just in time for the wholesale transfer of American manufacturing to China under the auspices of the “opening” of the Asian continent.

Nearly half a century later, “the best enemy money can buy” – to borrow Antony C. Sutton’s relevant turn of phrase – was sold to the American public by Donald Trump, whose anti-China rhetoric during his presidential campaign and policies of his admininstration would color the new Cold War with China and usher in what independent researcher Alison McDowell has described as “digital chattel slavery.” McDowell describes that slavery in terms of the burgeoning blockchain-anchored human capital markets, which are anchored to an emerging biosecurity state being rolled out under the guise of the pandemic, covered in a later installment of this series.

Setting up the “new Cold War”

On February 10, the Department of Defense released a fact sheet announcing plans to establish a “China Task Force.” It was to be headed by Defense Secretary Lloyd J. Austin; advisor and former Executive Vice President of the D.C.-based national security think tank Center for a New American Security (CNAS), Ely Ratner; and 15 yet-to-be-announced “civilian and uniformed” DoD employees.

The task force’s unveiling came just days after Austin released a statement addressing the Pentagon’s intention to reassess the U.S. military’s “global posture” away from the counterinsurgency missions that have characterized it since 2001 and back to a high-intensity war footing between nation-states.

In 2014, during his time as an associate political scientist at the RAND Corporation, Ratner co-authored a research paper titled “China’s Strategy Toward South and Central Asia,” examining the threat posed by China to U.S. interests in Central Asia. He concluded that no substantial threat existed. Ratner and his co-authors dismissed China’s show of strength in the region as an “empty fortress” – a reference to one of the 36 Chinese stratagems of war (ostensibly devised in the Dynastic Era), which involve deceiving the enemy through reverse psychology.

Ratner’s views seem to have undergone a transformation since he served as then-Vice President Joe Biden’s deputy national security advisor in 2015 and as a Maurice R. Greenburg senior fellow for China studies at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) in 2017.

Soon after Ratner joined CNAS, he began publishing far more hostile takes on China. He decried the failure of America’s noble expectations of “openness” with China, met by what he called “defiance” by Xi Jinping, and called for “clear-eyed rethinking of the United States’ approach to China” without concern for the potential risks of “inviting a new Cold War.”

In January 2019, Ratner issued a statement in his capacity as executive vice president of CNAS praising Trump’s aggressive trade policies against China and putting forth a kind of draft of the “whole-of-government approach,” so named in a follow-up report by CNAS one year later. That report, co-authored by Ratner, was aptly titled “Rising to the China Challenge” and called for that same “whole-of-government” approach that has now been adopted by the Biden White House and enjoys enthusiastic bipartisan support.

Republicans are eager to join in on the Cold War revivalism sweeping through Washington. This was attested to by a telling spat that took place during a House Armed Services Committee Zoom session in the summer of 2020 over a relatively small item in the 2021 Defense Authorization Bill. Silicon Valley’s Democratic Congressman Ro Khanna was trying to transfer approximately $1 billion from the $740.5 billion defense budget to a pandemic preparedness fund. Specifically, he was trying to take it from a $1.52 billion line item apportioned to Northrup Grumman’s $100 Billion nuclear missile project contracted by the U.S. Air Force. The proposal enraged Republican Liz Cheney of Wyoming, who blasted Khanna for suggesting the money should go to a pandemic preparedness fund since, according to her, “the Chinese government, the Chinese Communist Party, is directly responsible for the deaths that we’ve seen in the United States and around the world, directly responsible for the economic devastation.”

Cheney found it “shameful” that a “member of the United States Congress” would propose diverting funds away from a nuclear deterrent device (of which the USAF plans to buy 600) to a pandemic response initiative.

Cheney’s tantrum ultimately saved Northrup Grumman’s down payment. But to fully grasp the logic behind her reaction we have to go all the way back to the beginning — to what makes America what it really is and the driving forces that have kept this nation at war for virtually every minute of the twenty-first century.

The ground rules of free market capitalism

Long before Henry Kissinger took his poisoned olive branch to Beijing in his infamous secret trip to “open” China to American commercial interests, agents of colonialism had been reaping massive fortunes from illegal opium smuggling operations carried out across the Asiatic continent as they drove a stake into the heart of one of the world’s oldest civilizations in their relentless quest for capital accumulation.

American drug cartel capos like Thomas Handasyd Perkins and his brother James had started out in the slave business, trafficking human bodies on commission between Boston and Cap-Français in Saint-Domingue (in modern-day Haiti), in addition to commodities like flour and cod. The Haitian Revolution made business even more profitable, as Perkins, Burling & Co. became one of the main suppliers of food and ammunition for the French army.

The Perkinses moved on from the slave trade in 1793 to the far more lucrative China trade,, which produced enormous profits for them and the rest of the fledgling Eastern Establishment. Worthless U.S. banknotes, which neither ports of call nor Chinese suppliers of the prized silks and teas in demand throughout the Western world would accept as payment, had to be substituted for with Turkish opium paste.

The Perkinses’ experience and their connections to a powerful Chinese merchant known as “Howqua” made their ventures particularly successful — so much so that the Perkins-Howqua partnership was the sole focus of a 1821 inquiry by the British House of Lords into the inroads being made by American smugglers into the Crown’s massive opium trafficking business through the East India Company.

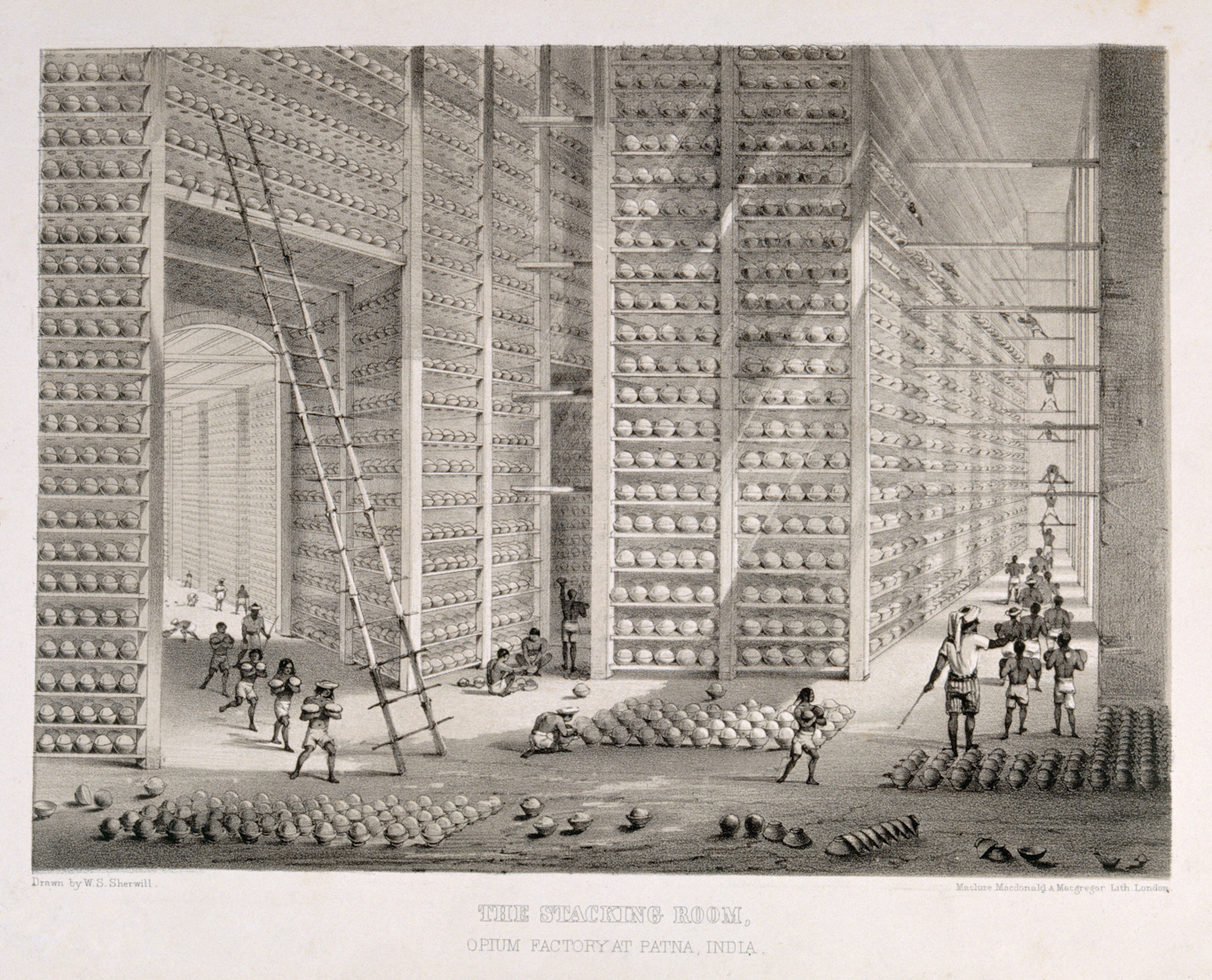

A stacking room in an East India Company opium factory circa 1850. Credit | Wellcome Collection

The scale and scope of the Perkinses’ operation has been described by Michael E. Chapman, associate professor of history at Peking University, as a “transnational conglomerate, operating at a supra-governmental level.” According to Chapman, the Perkinses’ ocean-faring business practices — which included spreading risk via cargo insurance, pooling investors for each voyage, and apportioning capital across vessels — laid down the “ground rules that underwrote American free-market capitalism.”

Such ‘ground rules’ weren’t entirely unprecedented in history and virtually all of the ‘free-market’ innovations mentioned by Chapman had already been put into practice by maritime superpower Venice centuries earlier. But, the British and their colonial cousins in the United States – who were in many ways directly descended from Venetian merchant traditions – enjoyed advances in shipbuilding, which made the frequency and volume of their exploits much greater.

An obsession with the Far East was another idiosyncrasy they inherited from their sea-bound forbearers, albeit couched in a much less romanticized view of the Orient than that of the legendary son of Venice, Marco Polo.

Shooting down from the moral high ground

The colossal fortunes accrued by the Perkinses and other drug smuggling magnates like Samuel Wadsworth Russell were sometimes funneled into educational institutions like Yale and Harvard universities. The Boston Athenæum, one of the nation’s oldest libraries, owes its existence to the Perkins brothers, who donated the lion’s share of its initial funding; while the notorious Skull & Bones Society at Yale was founded by William Huntington Russell, cousin of Samuel Russell, who by that time had overtaken the Perkinses to become the largest opium smuggler in China.

The celebrated academic institution located in New Haven, Connecticut, has, in conjunction with Protestant missionaries, played a central role in America’s relationship with China over the course of nearly two centuries. Western medicine, in particular, was the vehicle used by religiously-inclined foreigners motivated to convert the heathen masses of China and the opium trade loomed large in their efforts. As the “vanguard of Western cultural penetration,” Christian missionaries performed a crucial function in the protracted entrenchment of American commercial interests in Asia through the establishment of medical practices in Guangzhou and, eventually, other parts of China.

The first Western-style ‘hospital’ in China was founded by Peter Parker in 1835, fresh from obtaining his Medical Doctor’s degree from Yale Medical School and ordained as a Presbyterian minister upon completion of his theological studies at the same institution. Opened as an “eye infirmary” in Guangzhou, the project was admittedly just a means to gain the trust of the locals in order to sell them on the Judeo-Christian concepts Parker was keener to impart. An initiative of a Christian missionary organization called the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM), the medical venture proved to be more profitable than expected and the infirmary was expanded to treat multiple diseases with the support of American businessmen in the port city.

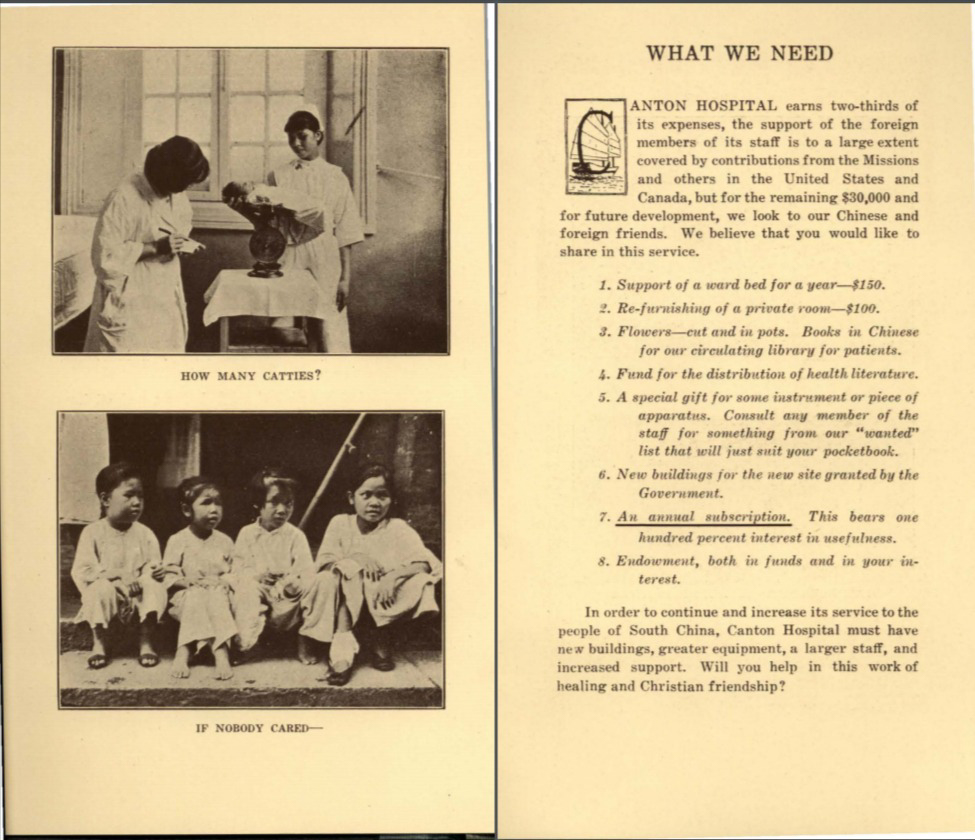

A brochure soliciting donations for Parker’s Canton Hospital circa 1920. Credit | Trinity College Digital Repository

Subsumed under the Medical Missionary Society in China three years later, Parker’s hospital depended heavily upon the contributions of American businessmen – the majority of whom were involved in the opium trade – and particularly dependent on the financial help of none other than the Perkinses steadfast associate Howqua to keep its doors open. One exception to Parker’s opium-linked patrons was David Olyphant, co-founder of Olyphant and Co., which engaged in the trade of silk and heavy fabrics and allowed Parker to utilize the company’s warehouse space in Guangzhou to house patients.

Olyphant, however, was among a minuscule minority who opposed the opium trade and, perhaps to his business’ ultimate detriment, did so vocally. Other Westerners in China who may have harbored reservations about “one of the greatest evils afflicting Chinese society” kept their misgivings to themselves, including China’s first missionary and founder of the ABCFM, E.C. Bridgeman, who preferred that his views remain hidden from the public given the political and economic consequences of broaching this “most delicate subject.” Bridgeman eventually felt secure enough in his position to openly challenge the opium trade, along with other missionaries in the port city, but refrained from directly attacking the British and American merchants responsible for the trade itself. After all, it was these same merchants that funded the Protestant missionary’s philanthropic ventures.

The re-education of China

Any attempts to curb the opium business were quashed by the foreign interests and governments that drove it and the illicit drug continued to flood China over the next several decades, leading to repeated clashes with Western colonial powers known as the Opium Wars of 1839-42 and 1856-60. Faced with the relentless destabilization campaign by British, French and American forces, along with tacit approval and cultural subversion by Christian missionaries, China would grow increasingly weak and succumb to the demands of its enemies.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, the erstwhile kingdom had become highly fragmented both geographically and socially. The British had managed to tear Hong Kong away from China in the Treaty of Nanking at the conclusion of the First Opium War and reliance on Guangzhou diminished as other points of entry to the mainland were progressively granted.

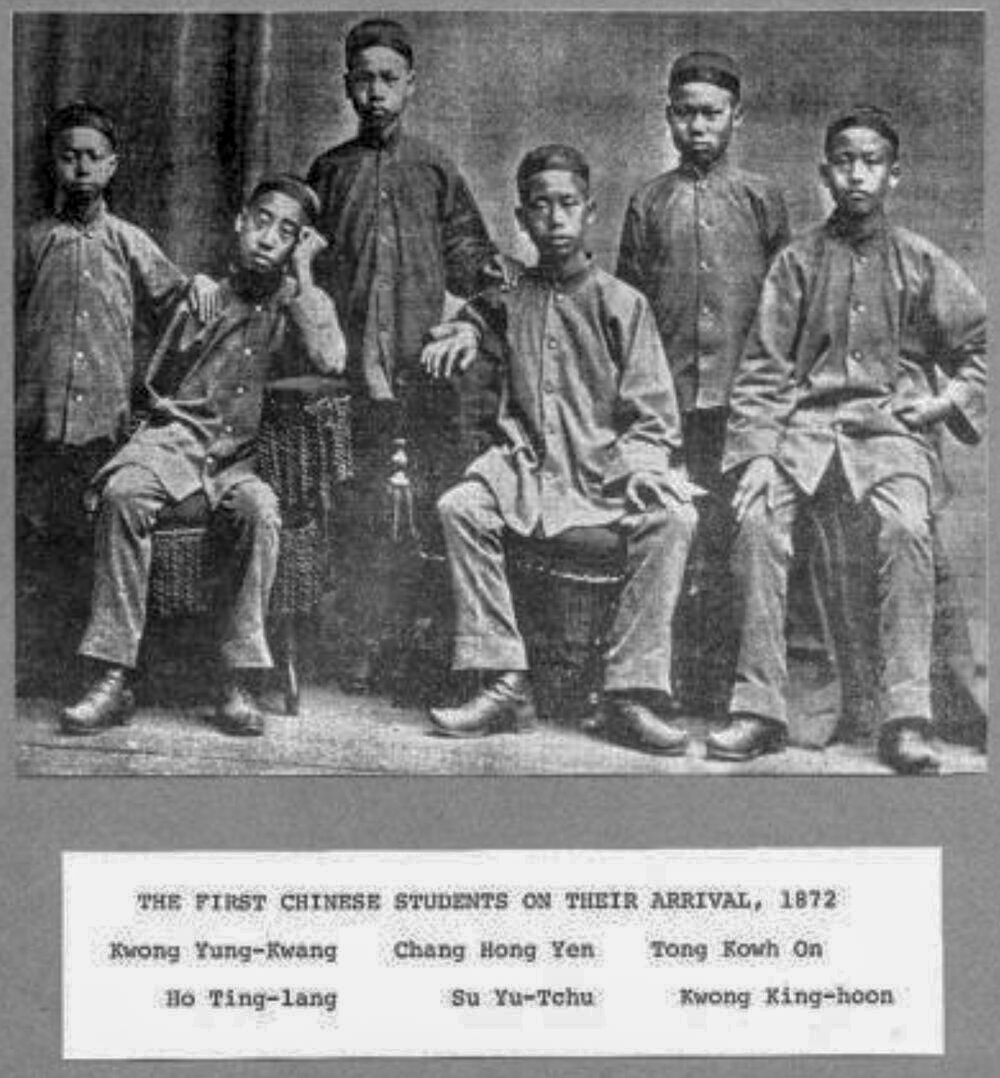

Yale University, in tandem with the missionaries, continued to cultivate its leading role as a purveyor of Western knowledge among Chinese nationals and in 1850, Samuel Robbins Brown, an ABCFM missionary and Yale graduate, brought a young man he’d had under his tutelage since the age of 19 at the Macau Missionary School to pursue a four-year college degree at the Connecticut campus. Yung Wing became the first Chinese student to graduate from an American university and would establish the Chinese Educational Mission – a program that placed Chinese students in schools throughout the United States in the 1870s.

The first Chinese Educational Mission students arrive in Hartford circa 1872. Credit | Connecticut Historical Society

According to Yale’s website, these select pupils went on “to become leaders in fields such as engineering, diplomacy, and academia.” One of these bright lights, Tang Guo’an, would become the first president of Tsinghua College (today Tsinghua University), a prestigious institution of higher learning in China and Xi Jinping’s alma mater, which to this day maintains a close relationship with some of the most powerful Western business leaders and unsavory former government officials of our time.

The symbiotic relationship between Western and Chinese academic circles only intensified as the nineteenth century drew to a close and, by the beginning of the next one, these became more formalized through federal programs like the Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Program of 1908. This program was the result of a Congressional resolution intended to return a portion of the $333 million punitive settlement with which Western powers had collectively saddled China after the Boxer Rebellion, but was instead used as a means to effectuate “American-directed reform in China” by funding the education of Chinese nationals in U.S. colleges.

In 1906, three Western Christian missions — including the aforementioned ABCFM, along with the London Missionary Society and the Medical Missionary Association of London — founded the Peking Union Medical College (PUMC) in cooperation with the soon-to-be overthrown Qing government of China. Two years after the Xinhai Revolution that put an end to China’s Imperial Dynasty, the Rockefeller Foundation assumed financial control of the PUMC and carried out the “transfer of Western science and medicine to China,” which included specialized technology and training methods as well as funding staff member salaries, and which over the next four decades, would amount to the creation of “a new medical elite.”

The Rockefeller dynasty

The wealthiest of America’s newest crop of plutocrats, John D. Rockefeller, had developed lucrative business interests in the Far East through his oil company and, like his predecessors, bolstered these through philanthropic contributions to missionary outfits in China. The Boxer Rebellion and growing resentment of the Western presence in China moved the robber baron to redouble efforts to restore American tutelage in the Asian country.

In 1908 — on the advice of his most trusted advisor, Baptist minister Frederick T. Gates, and future University of Chicago President Ernest DeWitt Burton — Rockefeller funded a program called the Oriental Education Commission at the university, itself a Rockefeller-funded institution.

The Commission’s report determined that the establishment of an educational program in China would bring about the desired “social revolution” by inculcating Western moral and political standards in the Chinese people. The initial recommendations were tweaked by Gates to circumvent the perfectly justified animosity of the Chinese to the West’s concepts of morality and society. In order to clear this hurdle, Gates proposed an alternate approach: to use medicine to do “what we had failed in our attempt to do in University education.”

Not without opposition by those who believed a university project was a better bet, the newly-established Rockefeller Foundation would make the first of many investments in medical programs for China, in part to avoid too much scrutiny from the U.S. government into its foundation and, as John D. himself presciently described the choice, to focus on medicine as “a nonpartisan work and one which would interest all of the people regardless of the government change.”

Members of the Rockefeller’s Oriental Education Commission visit Chengdu, China in 1909. Credit | University of Chicago Photographic Archive

The China Medical Board (CMB) was created by the Rockefeller Foundation in 1914 to grant assistance to medical schools in China, which were all operated by the Protestant missions like the ABCFM and their British and Canadian counterparts established since the early nineteenth century. In 1917, the CMB purchased the Peking Union Medical College campus for $200,000 and inaugurated the pre-medical program of the new PUMC.

The institution remained under the control of the Rockefeller Foundation until Mao Zedong nationalized it in 1951 and merged with the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS) six years later. While China’s communist revolution might seem like a watershed moment that closed off Western access to and influence over China’s scientific and medical establishment, John D. Rockefeller’s confidence that his investment would survive “regardless of the government change” is supported by a 2015 paper published by the University of Cambridge, which looks at how PUMC remained “a prominent symbol of Western medical science and education in China” from 1949, when the People’s Republic of China was established, through 1985.

The Cambridge study reveals how it was the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), itself, that took on the task of protecting PUMC’s position as the “premier establishment of Western biomedicine in China,” despite the strong criticism of any form of Western imperialism that was so prevalent during the early years of Mao’s reign. In addition, the guiding tenets of the CCP’s health policy, as delineated by Mao in 1950, contradicted PUCM’s own foundational tenets. In order to reconcile this inconsistency while maintaining the school’s methodologies and Western approach to medicine, an anti-imperialist discourse was promoted at the institution and its name was changed several times. But, according to the paper’s author, Mary Brazleton, no significant reforms were carried out at PUMC and, until the cultural revolution of 1966, the institution continued to operate much as it had before 1949.

Red Scare on life support

Just four years later, Richard Nixon’s secretary of state, Henry Kissinger, made his ‘secret’ trip to China and started down the road to a Sino-American rapprochement that would in time fully restore the West’s presence in the communist nation. The scientific and medical “elite” envisioned by Rockefeller’s philanthropic venture would reassert itself, as well, with a growing level of cooperation between Chinese and Western research scientists.

Economic cooperation with communist China would also receive a major and much-needed boost through yet another Rockefeller creation called the Trilateral Commission, a policy group formed and chaired by John D.’s grandson, David, which would begin rebuilding the Western commercial networks in China that had atrophied over the course of Mao’s revolution.

Though billed as an organization to “foster closer cooperation” among Japan, the United States, and Western Europe, the Commission’s fundamental purpose was to keep communist China afloat and pave the way for American manufacturing firms to exploit cheap Chinese labor – slave labor, in some cases – by moving operations from more expensive (and organized) labor in the United States and Mexico.

By the time Jimmy Carter was elected president and had appointed no fewer than 17 Trilateral Commission members to his administration, China had started to recover from the brink of collapse. A series of contracts with Western companies — including deals with Ingersoll-Rand, Boeing, and U.S. Steel — had helped to revitalize its failing infrastructure. Sweet insider deals, further illustrating the hypocrisy of American capitalists, were also there for the taking, one example being the soft-drink monopoly in China given to major Carter supporter, Trilateral Commission member, and Coca-Cola CEO John Paul Austin.

Kissinger, left, and Chinese premier Chou-En-Lai drink a toast in the Great Hall in Beijing, Nov. 10, 1973. HWG | AP

Rockefeller’s own Chase Manhattan Bank and Citicorp (in which the Rockefellers also had important interests) benefited the most from the Trilateral era, which lasted well into Reagan’s time in office. The latter bank highlights the very real historical links between modern-day American plutocracy and its ignominious origins in the slave and opium trade. Nearly a century after T.H. Perkins Co. had dumped its first illegal drug shipment in Guangzhou, James H. Perkins’ namesake and grand-nephew in 1929 became chairman of National City Bank, which later reorganized as Citicorp in 1967.

Well into the twenty-first century, the mission to rescue red China is complete and its relationships with the pinnacles of Western oligarchic power have been restored to shining beauty. Less than a decade ago, Blackstone CEO Steven Schwartzman founded a scholarship program at Tsinghua University to educate the “next generation of global leaders,” boasting a star-studded advisory board featuring former French President Nicolas Sarkozy, indicted in 2016 on corruption charges; Nixon’s “back channel” man to China, Henry Kissinger; and none other than insider hatchet man of the 2008 subprime mortgage debacle Henry “Hank” Paulson, who also shares an honorary membership in another Tsinghua University program with the former CEO of AIG — a company, holding a major stake in Blackstone, that was the linchpin of the “great recession” that set the stage for the rise of the fourth sector.

The not so New World Order

Founded as American Asiatic Underwriters in Shanghai in 1919 by Cornelius Vander Starr, American International Group (AIG) has never strayed too far from its government spook origins. Vander Starr was an American intelligence asset who collaborated extensively with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursor to the CIA. His New York office space doubled as intelligence fronts and he was U.S. Air Force Commander Claire Lee Chennault’s chief handler, having been a U.S. Air Force pilot who’d been tasked with putting together a covert, OSS-funded, 100-plane bomb wing to be flown by American and Chinese mercenaries against Japanese targets during WWII. The “Flying Tigers,” as the bomb wing is known, was initially intended to prop up the Western-backed government of Chiang Kai-shek, but would eventually partner with RAF squadrons to protect British colonies in Southeast Asia as well.

Vander Starr’s protégé, Maurice “Hank” Greenberg, would take over Starr’s insurance business as the company’s CEO in 1968 and transform it into the global powerhouse it had become just prior to the 2008 financial crisis, when its stock had reached stratospheric levels. During his tenure, Greenberg continued the firm’s strong focus in China and would, in turn, become one of the most important figures in the reopening of China after his old friend Henry Kissinger’s trip to Beijing in 1971 served to land him the first foreign insurance contract with China.

In 1987, Greenberg appointed Kissinger to be chairman of AIG’s International Advisory Board, while he went on to establish deep ties with the People’s Republic of China, sitting on the International Advisory Council of the China Development Research Foundation and the China Development Bank. Despite admitting to massive accounting fraud in 2017 and plundering his retirement plan as revenge for his 2005 ouster, Greenberg remains on the Advisory Board of the Tsinghua University School of Economics and Management alongside Paulson.

AIG was the center of the 2008 credit default swap (CDS) storm. The biggest insurance and investment firm on the planet had the largest exposure because it had bought all of the risk when it insured the CDS transactions of banks and pension funds all over the world. So, when the house of cards came tumbling down and AIG began defaulting on every claim, the fate of the global financial system rested on its shoulders.

Outrage over Wall Street’s irresponsibility was met with a promise to conduct its business in a more responsible manner and the idea of “ethical investing” was born. In reality, the concept wasn’t so new. Protestant missionaries in China had tried their best to place an aura of righteousness over the depraved capitalist instincts of their merchant compatriots, but the ruse never quite prospers.

At the end of the day, it all comes down to closing the sale and if that means disgraced British Prime Minister and Schwarzman Scholar advisory board member Tony Blair has to go out and hawk COVID-19 vaccine credentials to convince you to buy in, then – as will be made clear in Part III of this series – that’s exactly what he’ll do.

Raul Diego is a MintPress News Staff Writer, independent photojournalist, researcher, writer and documentary filmmaker.

https://www.mintpressnews.com/western-capitals-long-china-mission-opium-covid-vaccine/275573/

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home