Three Radical Measures for Delhi

November 24, 2020 | Romi Khosla

This is a free article from Marg's September issue 2020: A Species of Change?, published in print with the title Delhi: Makings of a 21st-Century City

We are not equipped to pursue progress any more. By losing our ability to live in kinship with the environment and pursuing instead the accumulation of material things, we have broken our link with nature—more so during the last seven decades, when we had the opportunities to correct ourselves. We became fully occupied instead in the praxes of Capitalism, Socialism, Liberalism, Neoliberalism, Communism, Free Marketism etc. During this period, our elite indulged itself, breathing in the dense fog of globalization surrounding us; here was a blindness that has led the whole country to a crossroads where we now have to make an unenviable choice.

Travelling on one road helps one acquire a knowledge that is steeped in theories and ideologies and promises of a utopia at the end of it, an end to which one never arrives because of its perpetual deferment. Another road leads to a place where one can engage in imaginative constructs about a hidden pre-European golden civilization. Yet another takes us to places where we can see for ourselves scripted evidence of the unstoppable biological and social evolutions of Charles Darwin and Karl Marx, who had clarified that mankind had evolved to reach a superior place, higher than the wilderness of the natural world and all its species.

We stand now, no longer able to find our way through the conflicting theories of epidemiologists, economists and experts, who predict that this may be the beginning of an era of fearful occurrences. We are, indeed, lost at the crossroads, having lost our bearings in the natural world.

We could have taken the experts’ pronouncements seriously had they revealed that all roads and solutions would lead to the broken limits of growth, excessive abuse of nature and blind admiration for the obscene accumulation of wealth. We know now that the natural balance between the earth, nature and mankind is skewed and the mess has brought the most suffering to those living in our cities and villages. We just saw it happen.

In hindsight, all of us have already paid heavily for that deceptive future dreamed up by the philosophers of the Enlightenment. We can see from the crossroads that on every road before us there are a few prosperous gated palaces on one side, and on the other, a landscape full of graveyards where lie those who became fodder for the violence needed to pursue the imaginary utopias of the philosophers who had roamed the world, seen its incredible diversity and concluded that it all needed to be ruled with a grand strategy of controls.

Our universal education system assures us that the achievements of science, public health and the spread of greater liberty have been delivered—but only to that side of the road where an insignificant proportion of global society lives in gated communities.

These are granular gains, but do they justify the deliberate murder and annihilation of over 250 million living beings during the last two centuries? External actions are a result of internal processes: during the fight for India’s independence, our contentious external actions against the earth, nature and other human beings brought us to fear fellow citizens and the future.

India’s Vulnerable Location

India is located between the newly enlightened Western world and the ancient civilizations of Asia. Far from being in the middle, we are at the perimeter of the global order, deep inside that macro-zone of instability. There is no available seat at the high table of stability. We are on our own and need to prepare ourselves for every type of eventuality for the simple reason that there will only be crumbs from that high table for sharing amongst dozens of other desperate countries, such as ours, no matter what sort of demagogue ascends to rule us. Now onward, whenever public health and climate-related black swan events hit us with expected frequency, we have only our own solutions to see us through the catastrophes. To cope with our future, to survive it, we will have to come to terms with the absurd realities of our social, economic and

environmental sectors, which have distanced us from the natural world. Each of these sectors remains fragile and any or all of them could get waylaid: we saw how a virus paralysed civic governance.

Historically, our predicament today is the price we have had to pay for having faith in leaders who had no intentions of being responsible for providing us a safer, long-term future. Their ideas about industrializing our country and becoming a world power remain delusional as do their hopes of an urban landscape that emulates London and New York. In the absence of any safety net of welfare, our many diverse communities can no longer look towards a callous government, but arrive at solutions on their own.

Preparing for the Future

This essay describes a way to prepare Delhi for the future, for autonomy. The capital is a fractal of all our cities, of the entire country, and we need to prepare it for the coming century. Its ratio of income disparities between the richest and poorest stretches across a dark gap of over 1:50,000, a gap caused by decades of callous governance.

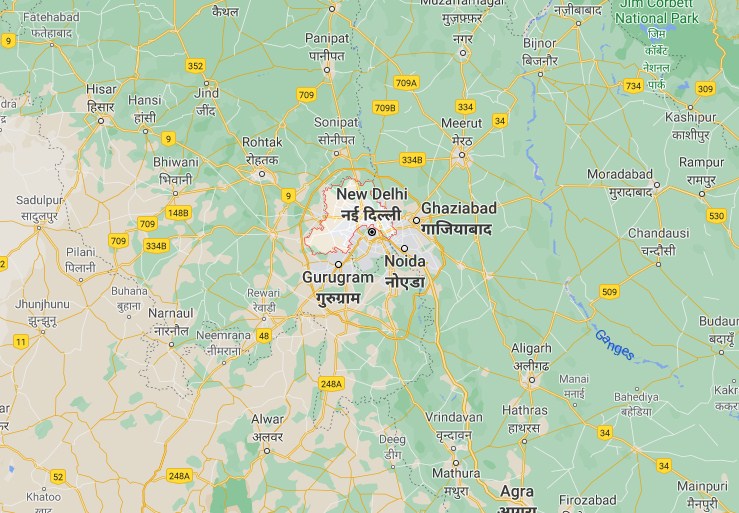

Image: Map of the National Capital Region showing the 24 districts in Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan that were identified by the NCR Planning Board Act in 1985. The number has been increasing ever since. Today, Delhi itself has 11 districts. Courtesy Romi Khosla.

Delhi is not a stable entity anymore and the post-COVID-19 situation has confirmed its fragility. Not only does Delhi have to urgently change, but so do our other cities—if we are not to join the ranks of failed countries—and it can begin with the transformation of its socio-economic urban geography.

Delhi was once the symbol of our sovereignty and new nationhood, the nerve centre and seat of elected governments, a place from which our borders were kept secure and—I wish I could have added—“from where its citizens were fed, housed and looked after”.

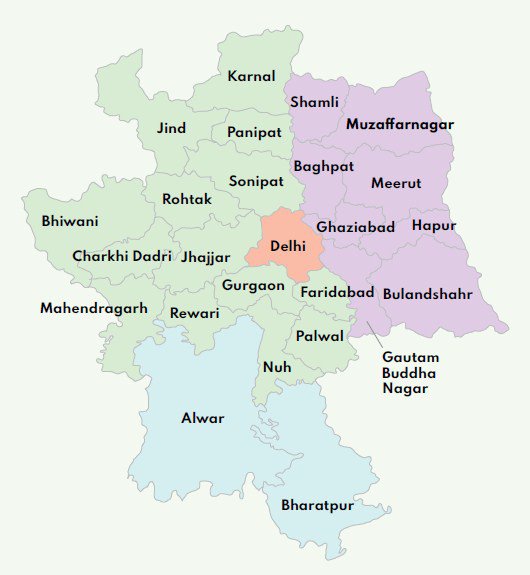

Image: A living landscape: The Royal Zenana at Faizabad, 1765, attributed to Faiz Allah. Courtesy The David Collection, (46/1980) Copenhagen. Photograph: Pernille Kemp.

Seven decades after appointing it the capital of the nation, it has evolved into a place where generations of its citizens who think differently are seen, not as wards and citizens, but as enemies of the nation and objects of surveillance. The city’s capabilities and potentials are bound up in its colonial past, resulting in it becoming an outdated symbol of 19th-century notions of nationhood. Our leaders use the city to enhance their political prestige by celebrating a stimulated sense of patriotism annually at the Central Vista, Rajpath, in a pageant where our multi-regional regiments step out in a parade and tractors tow cute floats from each state to remind us of our diversity and synthetic unity: all this is given the stamp of authenticity by the national anthem.

The Soviet Union preceded India with its May Day parade. Now as the Central Vista is altered, our rekindled patriotism will give us a new venue for parades, the kind with which Germany forged its frenzied pre-war nationhood.

Image: Nationalism being practised at the 70th Republic Day Parade, Rajpath, New Delhi, 2019. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Cities are not political instruments. They are the collective expressions of the consciousness, pride and varied imaginations of their inhabitants. The pride of citizens makes a city an instrument in the hands of those who govern.

Delhi is first a refuge to help us transcend the hostilities in our larger social and economic environment. We seek comfort in the density of life that cities offer. Amongst its many qualities, Delhi is also a fractal that reflects our muddled and dysfunctional national governance. The capital’s governance is contested by dividing it to ensure political distance between the elected Government of Delhi, the New Delhi Municipal Council, the Delhi Development Authority, the Army in its cantonment, the Ministry of Home Affairs with its Lieutenant Governor, and the Municipal Corporation of Delhi.

Unlike in a rugby scrum, however, here, the players are invisible and muzzle the autarkic voices coming from the distanced communities. The recent pretentious preparation of master plans and the tussle for the governance of Delhi simply reflect the obsession of rulers with grand strategies, but not an ability to engage with the community or promise it equity. The city’s economic and urban geography of the future—disguised as the master plan—is determined by the meek, who ignore the call for justice coming from the community living there and instead heed the voices of their masters.

Three Radical Measures for Delhi

A rearticulation of the principles of justice is the foundation for enabling a longer cycle of prosperity for all the communities living in Delhi. The unique productive and cultural identity of each is more important than their synthetic national identity. Engaging with justice involves listing mutual agreements and joint oversight of the communities and their leadership. Listing the conditions of justice involves compiling a roster of restrictions and obstructions in the way of the opportunities, potentials and capabilities of each community.

The district within each state is the point of application of the principles of justice. Currently, India has about 736 districts, which will become the component hub of governance and justice in a radically decentralised system of government. Enumerating the inequalities and asymmetries that exist between the communities resident in each district will enable the leaders to know how to address the constraints in the interests of justice. The availability of resources—natural and financial—in each district and with each community is one of the elements of self-sufficiency. This will include access to solar power, urban farming, waste disposal and harvested water supply to incubate new opportunities, promoting autarky and social justice.

The capital city should be the first to receive these radical reforms, its governance acquiring new democratic responsibilities which can be deepened at the community level.

The first measure incorporates the inclusion of the existing National Capital Region (NCR) into a newly expanded City State of Greater Delhi. From the present 11, it can expand to 35 districts of self-governance. This expansion of Delhi’s geographical limits is imperative for the city state to become self-sufficient and be able to support its residents within an area of 55,000 sq. km. The second measure monitors the overdue national umbrella of universal social welfare over the City State of Greater Delhi. Such a measure will bring in phased expansion, beginning selectively with cover for the extremely poor. Rwanda, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Sri Lanka, Cuba and many other countries have adopted it. India, which is far behind in this, will have to pioneer such a measure in all its states.

The third measure will require the active decentralization of democratic power. Implementation of the 73rd and 74th constitutional amendments will empower municipalities, districts, blocks and panchayats to rule themselves and become nodes within a framework of self-sustaining hubs, which will form a net over the City State of Greater Delhi.

These transformations are, thus, not about Delhi changing its form. It would be easy to continue handing land to the builders and deceiving the inhabitants by pretending to plan for equality and fraternity while practising unjust architectural and social distancing: this has been the reality for decades. The new City State of Greater Delhi will not be a neo-socialist city of the past. It will remain a city of differences, but with equitable historical differences in the Rawlsian sense of fairness.¹

By adopting the Difference Principle, the varied communities agree to regulate their existing inequalities rather than let planners pretend to abolish them with top-down master plans. Every district and block community in the new city state’s democratic framework will agree on what constitutes shared basic liberties without obstructing free access to social media, public spaces, land purchases and appointment to public offices at every level of governance. Public lands owned by the city are regarded as commons and include properties and spaces used for cultural activities, such as music festivals, carnivals and farmers’ fairs. Such lands will include heritage properties, religious structures and, in some cases, agricultural fields and public infrastructure such as electricity or water distribution systems.

To enhance the proportion of locally available food in the region of the new city state, the urban fabric will have multiple small and large cultivated plots and rooftops for urban agriculture. These plots will be cultivated primarily for seasonal and perennial vegetables, distinct from crop supplies from the hinterland of the city state which are computed separately. Each area, occupied by a block of built-up space, will have an equivalent portion set aside for agricultural use or food production, which will be distributed on the basis of a new land use map, identifying potentially cultivable plots across the cityscape.

The New Socio-Economic Geography and Sanctuary of Greater Delhi

As a part of this initiative, new living landscapes can be formed and a new socio-economic geography put in place. This will not simply consist of beautiful natural spaces, but will emerge from new social contracts devised through legislation. Such laws will redefine the balance of responsibilities between citizens and their individual rights and the responsibilities of the state to protect them. Under such an initiative, it will be possible to shift the focus of stimulus down from state to district, and to the atomic mohalla and blocks where translocal poly-economies can interact and exchange with each other under the welfare system’s statewide safety net. The evolution of such a new urban and economic landscape will enable decentralized hubs of democracy and polycentric economies to be revitalized.

This proposal for the transformation of Delhi is not concerned with its density or the physical planning of its forms. The aim is to transform Delhi into a natural sanctuary by restoring natural environment and self-sufficiency to its inhabitants: the National Capital Region will be able to see a significant increase in the extent of its natural habitat and significant decline in its population.

Delhi’s new identity as a city state, incorporating the larger capital region, begins by planning the entire territory of about 50,000 sq. km as an integrated network of 35 living districts, the basic cells that can power Delhi’s future urban economy rather than letting it continue as an unnatural, parasitic colonial city. The people will have access to greenery and picnic spots beside canals and rivers and be able to savour fresh vegetables, grown in their own courtyard gardens, rooftops and balconies.

Once established as a self-sufficient city, Delhi will also have its recreation facilities, creative communities, brokers and hustlers, criminals and charities, honest campaigners, corrupt politicians, commission agents, bureaucrats and policemen, all of whom are components of human settlements: their presence will depend on citizens who choose to indulge them.

This is not an obituary for Delhi, but a reliable way to keep the capital city vibrant and dynamic by integrating its economic and cultural activities. The city’s density has made it vulnerable to the pandemic, but it can recover without the over-crowding and domination of city life by the private car. With the relocation of workplaces close to living spaces, the extensive use of public transport and the focus of citizens on self-reliance for energy, livelihood and food, Delhi can become the city of the 21st century. This will open up new opportunities for prosperity when the micro-district level production centres become the base of a new macro state-level economy.

The reclustering of Delhi’s economy through hubs in each district is the only way to re-engage with the lives of the unemployed and dislocated urban farmers. The formation of a re-federated Delhi with steady state supply and demand will enable the weaker and poorer zones to use the instruments of reform to join the prosperous zones of the state. Regional ethnic, religious and productive communities can thus discover their own economic capabilities and independence without relying on the dwindling centralized and monopolist sectors of the economy to generate cash incomes.

As the new City State of Greater Delhi begins to rise up after the ghosts of COVID-19 have been banished, when the planning of district-based micro-regions of the state have returned to be democratically governed and the empowerments of the 73rd and 74th constitutional amendments have been fully implemented in the districts, good local urban planning at the human level can be restored. That is when a new long-term history will begin and make the state a sanctuary.

The beginning is in reallocating space. With the introduction of pedestrian-only zones, its multiple centres will be places where residents can walk to work on widened sidewalks or use cycles and public transport. The ratio of public to community space will radically change with reduced reliance on the private car.

Once residents and retailers are no longer crammed into spaces off the street and a dense network of parks and local markets are opened up to replace parking zones, the city will be able to have a better infrastructure to respond to an emergency, such as a pandemic or global warming.

Image: The impractical density of Delhi. Courtesy Francisco Anzola and Flickr.

The dangers of global warming will inevitably influence the urban planning of a capital city. Scientists have forecast that India is going to be particularly vulnerable to risks from rising temperature which will, in turn, result in drought and migration. Such migration will be much larger in scale than the one impelled by the pandemic, with the capital city being particularly vulnerable. Therefore, it will need to have a defence strategy in place to deal with migration while ensuring a close relationship with the natural world, within which civic amenities such as parks, gardens and affordable housing will be located.

The rulers of Delhi have much to learn from Paris Mayor, Anne Hidalgo, who wants to turn the capital of France into a “15-minute city” which represents the results of radically re-planning it at a micro level in such a way that residents’ needs are met within a 15-minute walking or cycling distance from their homes.

Conclusion

Delhi is a complex organism, not a political instrument, and needs to change from paying 19th-century obeisance to the past. It can no longer remain irretrievably unsustainable and continue to be governed by outmoded economic and planning models, centred on the accumulation of wealth through the grabbing of community lands and indifference to poverty. The declining allure of old standards can help inspire the adoption of a new development for Delhi, enabling prosperity through the adoption of natural ways of urban living.

Endnotes

1 John Rawls (1921–2002), American political philosopher, proposed the Theory of Fairness and the Difference Principle within it states that fairness needs to recognize that individuals possess varying amounts of resources, which also depends on factors such as different capabilities and potentials.

https://marg-art.org/blog/delhi-makings-21st-century-city?fbclid=IwAR32KSyWRnUGdG5v8Lbi-GzhSohLfVkSYaqiyHyn4z1ApNTz3tji1CvBo_U

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home