The Long Shadow Of The 1953 Coup

Coup 53 is a timely reminder that regime change is wrong and destructive even when it "works."

The 1953 U.S./U.K.-backed coup against Iranian Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh was one of the pivotal events of the early Cold War, and it continues to have consequences for Iran, the surrounding region, and U.S. foreign policy almost seventy years after it happened. It is in some respects the original sin of U.S. Iran policy since WWII, and we are still living with the damage that it caused. Much of the turmoil and upheaval that have followed in the region have their roots in the American and British policy of interfering in Iran’s internal affairs and forcing a change in government.

Taghi Amirani’s excellent documentary, Coup 53, explains how the coup was carried out and details the role of the U.S. and U.K. governments in sponsoring and orchestrating Mossadegh’s overthrow. The film takes the viewer through the background to 1953, and then shows the links between the coup then and the subsequent developments in Iranian history. I was privileged to have the opportunity to view the film recently, and it is a shame that the documentary does not yet have the wider audience that it deserves.

The U.S. has acknowledged its role in the coup, but even now the U.K. does not officially admit its involvement. One of the interesting contributions of the new documentary is to confirm additional evidence that details the significant British role in the coup. Amirani reconstructs the story of how the coup happened, and provides a new generation with an understanding of the long-term effects of the coup on Iran and Iran’s relations with Western powers.

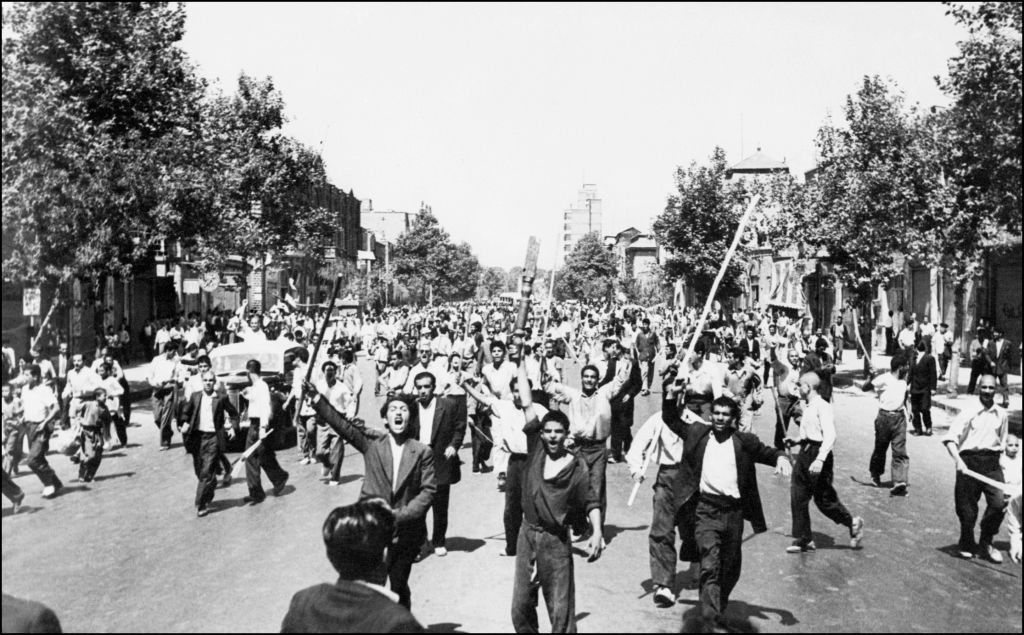

It is a beautifully filmed documentary. There is good reason that it has received standing ovations and effusive praise at the film festivals where it has been screened. Amirani has worked for more than a decade on this project, and he has put in an enormous amount of work into creating the final film. He has traveled to many different countries to find witnesses to the events before and during the coup, and he has woven together a compelling story from the testimonies he has compiled. Some of the key events of the coup are dramatized in animated sequences to recreate the chaotic days in Tehran in August 1953, and Amirani makes great use of contemporary newsreels and audio recordings to recreate the political mood at the time and to capture the views of the different parties involved.

There is a particular focus on the role of MI6 operative Norman Darbyshire, whose role in the coup Amirani seeks to recover. Using production notes from the End of Empire series, he has pieced together the U.K. role in the coup. According to the transcript among the production notes obtained by Amirani, Darbyshire stated that he was the one running the coup on the UK side. Darbyshire also admits to being involved in the assassination of Mahmoud Afshartus, the police chief in Tehran, whose demise paved the way for the coup.

Amirani tracks down evidence of Darbyshire’s involvement, and tries to find out why his account was left out of the earlier series. In one of the more remarkable parts of the film, he has the actor Ralph Fiennes recite Darbyshire’s transcripted remarks as if it were Darbyshire himself giving the interview. Darbyshire’s absence in the earlier End of Empire series was a significant omission then, because the Darbyshire transcript shows beyond any doubt just how extensive the British role in the coup was.

Regrettably, veterans of the earlier program have taken offense at the portrayal of End of Empire in the new documentary, and this has led to a legal quarrel that has prevented the new film from being widely distributed. This is all the more unfortunate because the story that Coup 53 tells backs up and builds on the work that the End of Empire series did on this moment in Iranian history, and it introduces that work to a new generation of viewers.

Amirani has grounded his interpretation in a deep understanding of the history of the period. The documentary includes important context from historians that have written about the coup, including Ervand Abrahamian and Stephen Kinzer. He speaks with several of Mossadegh’s relatives and colleagues to get their memories of the former prime minister, and we hear Mossadegh’s own voice from recordings of his speeches. He details the political upheaval in the years prior to the coup, but he also makes clear that the impetus for the overthrow was from outside Iran. This is an important challenge to the growing revisionism from some Iran hawks that we have seen in recent years.

There is a strong interest among Iran hawks in the U.S. and elsewhere to promote the idea that the 1953 coup was almost entirely an indigenous development with which the U.S. and Britain had almost no involvement. Some Iran hawks wish to lay the coup at the feet of Iran’s clerics in an attempt to tie it to the current Iranian government retroactively to Mossadegh’s downfall, and others hope to minimize the Western role to deny the responsibility that comes with toppling another country’s leadership. This weak revisionism has spread to government officials in Washington, and former Iran envoy Brian Hook was unironically citing these arguments in support of the Trump administration’s disastrous “maximum pressure” campaign as recently as last year. In Hook’s telling, “Mossadegh was overthrown by the religious establishment, the military, and the political leaders,” but historian Gregory Brew has explained why Hook’s claim is wrong and misleading.

Coup 53 demolishes revisionist claims, but it also does so while allowing some defenses of the coup to be heard. The film includes the testimony of Gen. Zahedi’s son, Ardeshir Zahedi, who still predictably justifies the coup as both necessary and not dependent on foreign backing. No one can still seriously credit the idea that Zahedi puts forward that Iran would have been dominated by the USSR if Mossadegh had stayed in power. The great fear that Britain and the U.S. had at the time was that Iran would succeed in being independent, and that is what they sought to prevent by removing Mossadegh by force. In the near term, they got their way, but it came at the price of many more decades of distrust and enmity between those two countries and Iran.

In the 1950s and later, the U.S. tended to see any non-aligned and independent country as a problem that needed to be solved. It is intriguing to consider what U.S.-Iranian relations might have been like if Washington had been more willing to respect Iran’s independence and sovereignty. Had the U.S. chosen a policy of noninterference in the early Cold War, how many other horrific policies might have been avoided? How many other countries might have been spared the effects of U.S. covert operations?

The film touches on the last years of Mossadegh and his burial at his place of internal exile. It is clear that Amirani holds Mossadegh in great esteem, both for his own qualities and for the Iran that he represented. There was a possibility of an Iran with parliamentary democracy, and that possibility was violently snuffed out in favor of authoritarianism and a “pro-Western” alignment. It is unfortunately a familiar story from the Cold War, and one that Americans and Britons should look back on with shame.

The story ends with an epilogue on the reign of the Shah and the buildup to the revolution. This illustrates how relatively brief the so-called “success” of 1953 lasted and the terrible price that the Iranian people have had to pay for that interference over the last almost 70 years. “I’ve always said that the 11th of February 1979 is in fact the 20th of August 1953,” Mossadegh’s former head of security says at one point. The coup casts a very long shadow.

Coup 53 is an excellent documentary and a fine work of true storytelling. The film makes the case that 1953 was not only pivotal for the future of Iran, but created a precedent for further covert regime change operations by the US in the ensuing decades. In that way, US foreign policy has been warped ever since by the belief that the coup had been a great success when it was actually a profound failure and betrayal of our own principles of noninterference and nonintervention. Taking the longer view, it has been a disaster by convincing American policymakers that regime change is an effective and desirable option in dealing with other governments. Almost seventy years later, we know this to be a lie. Coup 53 is a timely reminder that regime change is wrong and destructive even when it “works.”

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home