The worldwide push for racial justice has sparked discussion within some Muslim communities on the overly white illustrations of key figures in the Islamic tradition, particularly the twelve imams so revered in Shiaism.

by Alan Macleod While the vigorous and often bitter debate around depictions of “White Jesus” continues to rage, a similar, but quieter discussion is taking place within Islamic communities on the subject of overly white illustrations of key figures in the Muslim tradition, particularly the twelve imams so revered in Shiaism, an subsect of Islam that comprises approximately ten percent of the world’s Muslim population. Depictions of humans are far less common in Islamic art, especially in Sunni Islam which tends to have much more iconoclastic tendencies, but a growing number of Muslims are voicing their discomfort over how portrayals of these leaders make them out to look far more European than they were.

“If there is talk about anti-black racism and working against mental colonization, then it makes sense that Muslims, as well as Christians, decolonize these depictions of prophets and saintly people,” Dawud Walid, Executive Director of the Michigan chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, told MintPress. “It’s about time, to say it bluntly,” said Zeinab Chami, a public school educator from Michigan and a practicing Shia, “now is the time for a change.” Sakina Syedda, co-founder of the Shia Racial Justice Coalition, agreed, telling MintPress that Muslims too should question any implicit racial biases encoded in their day-to-day lives: “It’s something that we know needs to be addressed. And we are beginning to see efforts in doing so.”

The idea that Jesus — a Jew living in Palestine 2,000 years ago — was “white,” is so ingrained into the public consciousness that it appears as an uncontroversial fact to many. Fox News host Megyn Kelly laughed at the idea of a non-white Jesus, calling it “ridiculous.” “Jesus was a white man,” she said, claiming fourth century Saint Nicholas, born in southwestern Turkey, as one of her own too: “Santa just is white… he is what he is.”

If this level of understanding of one’s own culture is the norm, it is perhaps unremarkable to see the same in Islam. In the wake of writer and activist Shaun King’s comments that images of white Jesus should be removed (something that led to threats on his life), Georgia Republican Congressional candidate Angela Stanton King responded, “Threaten to tear down statues of the Prophet Muhammad and see how many death threats you get,” seemingly not realizing that Muslims would be all too happy to help her in her task.

In reality, the scholarly consensus on the historical Jesus is that he likely had a dark complexion, not unlike that of many living in the Levant or Arabia today. As The Atlantic’s Jonathan Merritt wrote in 2013: “If he were taking the red-eye flight from San Francisco to New York today, Jesus might be profiled for additional security screening by the TSA.” Like with Jesus, many of the key figures in early Islam were far darker than many often suppose.

“The reality is that perhaps almost half of the imams were what we would now call black; we would see them and think they are black or African-American,” said Chami, “And I don’t know why that would be hard for some people to accept. If that is the case there needs to be some soul searching done.”

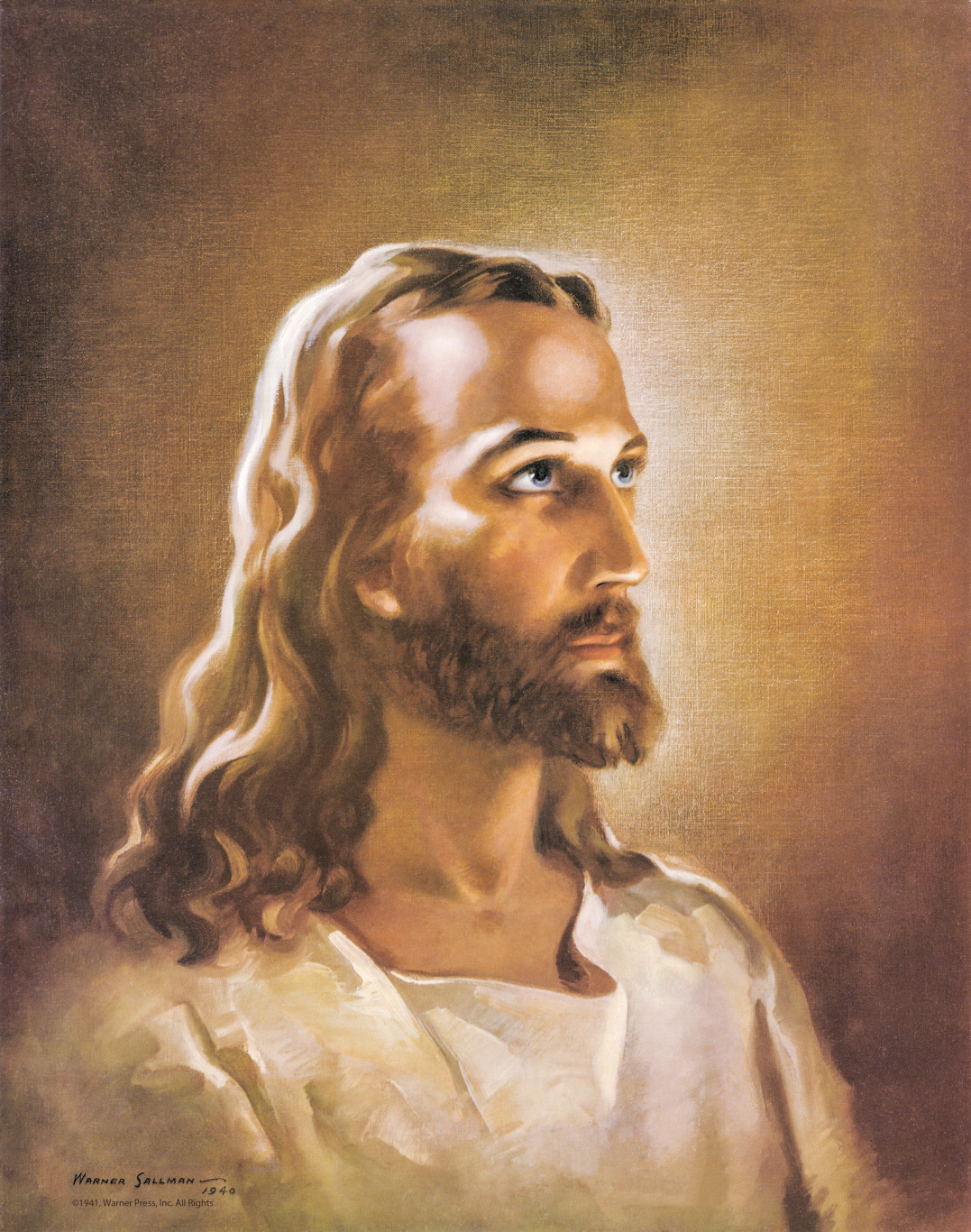

When most Americans imagine Jesus, there is a good chance that they are picturing the same 1940 portrait by Chicago artist Warner E. Sallman. Depicting Jesus as young, light-skinned, and Nordic-looking, “The Head of Christ,” is said to be the best-known American artwork of all time, having been produced over a billion times, the image adorns churches across America and was printed out and handed to troops in World War Two by the Salvation Army and the YMCA.

Warner Sallman’s now-ubiquitous “Head of Christ” circa 1940

Black Skin, White Masks

“The Head of Christ” is the epitome of the nineteenth and twentieth-century attempts to whiten Jesus. Throughout the period, European nations justified their imperial conquests on the ground that they were saving “savages” from damnation. The French called it their “civilizing mission.” Making sure that the image of religious authority looked just like they did was a crucial psychological weapon. By negating his true identity as a dark-skinned revolutionary with anti-imperialist tendencies, slavers and imperialists were able to better justify the strict racial hierarchies they were imposing around the world. If Jesus was white then authority is white. The radical postcolonial intellectual Frantz Fanon understood this explicitly. In his seminal 1961 work, “The Wretched of the Earth,” he wrote:

The Church in the colonies is the white people’s Church, the foreigner’s Church. She does not call the native to God’s ways but to the ways of the white man, of the master, of the oppressor. And as we know, in this matter many are called but few chosen.”

Malcolm X saw Islam as an escape from the fundamentally racist power structures ruling the United States. In his famous letter from Mecca, he wrote that:

America needs to understand Islam, because this is the one religion that erases from its society the race problem. Throughout my travels in the Muslim world, I have met, talked to, and even eaten with people who in America would have been considered white — but the white attitude was removed from their minds by the religion of Islam.”

Due to his experiences in Mecca, he began to see racism as a spiritual problem that required a spiritual solution. “In that same vein, we can see this move toward accurate portrayals of our holy figures as more than a decolonization of our minds,” argued Chami, “it can be a shift at the soul level, and, God willing, a healing process within our individual spirits and our communities at-large.”

Unlike with Christianity, the European depictions of the twelve imams who followed the Prophet Muhammad appear to have been far less deliberate, being brought from Persia. If that is the case, then is there really a problem? “Imagery is important,” says Walid. “Especially when we are talking about anti-blackness and trying to discuss history the way that it truly was. A number of those imams actually had African mothers and were described as being brown to black in skin color, so the depictions of all of them looking white is the erasure of blackness from within early Islamic history.”

Hussein Nasreddine, 50, shows his tattoo of Imam Abbas, who is said to have died in battle fighting a tyrannical government, May 10, 2016. Hassan Ammar | AP

Halema Wali, another co-founder of the Shia Racial Justice Coalition, also notes that black erasure can have a powerful psychological influence. “Anti-Blackness can be perpetuated by not having religious figures accurately depicted and/or whitewashed. Whether intentionally or not, what ends up happening is the desire to be close to whiteness not just through beauty standards, but also via religiousness,” she told MintPress.

For her colleague Syedda, the significance of the matter transcends the religious domain:

A lot of countries around the world have been colonized by European nations and that creates power structures and hierarchies that tie into what people perceive as powerful, beautiful or aspirational. And you can see that reflected in all kinds of areas…whether it is fashion or beauty or art you have to stop and think, and people are starting to do that a lot more now.”

The whole point of her religion, for Chami, is about grasping at the fundamental truths of existence:

We learn about Islam through the lives of the prophet and the imams. We think of these people as the living Koran; they lived the message of God. So when you see resonance with these people, you see yourself in them. There is power there. But when they look a particular way, a way that you are told is the best way and it doesn’t look like you, that can be problematic. And for me, the ultimate issue is that these white depictions are not the truth. And we do not want to perpetuate something that is dishonest…And this movement is moving us closer to truth.”

I Can’t Breathe

The power of the image to have a profound effect on behavior and the human psyche is precisely the reason this debate is happening at this moment. George Floyd was killed by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin on May 25. Without video of the incident, circulated widely on social media, Floyd would have become just another statistic: one of the 1,000 American victims of police violence every year, a footnote in history. Instead, the killing sparked millions to demonstrate nationwide and across the world and has completely changed the paradigm of how we collectively understand race. Ideas like defunding or abolishing the police entirely, once-fringe positions, have gained popular support almost overnight. There is a new sense that change is possible, and within grasp, if it is demanded. On the topic of inaccurate depictions in Islam, Walid said, “There are some people who always saw this as problematic, but now there are people who are actually organizing around the issue to bring awareness to it.”

Shaun King may have gone too far when he called for the removal of statues of white Jesus from Christian places of worship. His “damn fool idea” caused hysteria in conservative circles, with Fox News’ Tucker Carlson telling his older, white audience that “the mob” was coming to destroy their churches. But it also received huge pushback from the left, who saw it as an overzealous, iconoclastic demand. Yet on the issue of replacing Europeanized versions of Islam’s most important figures with more historically accurate ones, it appears that activists are pushing at a door already somewhat open. Syedda noted she had not received much resistance from her predominantly South Asian Shia community. “People of faith should be primarily interested in truth,” said Chami, adding:

For people who are resisting this movement because they see it as some kind of imposition of our modern notions of race and racial justice on to the ancient traditions of our faith, the reality is that we know that these depictions are inaccurate so why would we want to prevent them from being more truthful? Why have we accepted these inaccuracies without question? And why would we resist these changes? For people who are resisting this, and I know some people who are, I think they should all do some soul searching and ask why.”

Alan MacLeod is a Staff Writer for MintPress News. After completing his PhD in 2017 he published two books: Bad News From Venezuela: Twenty Years of Fake News and Misreporting and Propaganda in the Information Age: Still Manufacturing Consent. He has also contributed to Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting, The Guardian, Salon, The Grayzone, Jacobin Magazine, Common Dreams the American Herald Tribune and The Canary.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home