It’s older than you think: ‘Russian collusion’ has been a political weapon since the Cold War

Helen Buyniski

is an American journalist and political commentator at RT. Follow her on Twitter @velocirapture23

1 Mar, 2020 08:03

The “Russian collusion” trope didn’t just spring to life with US President Donald Trump in 2016 – accusations of taking help from the evil Russkies have dogged candidates who buck the establishment since the 1960s.

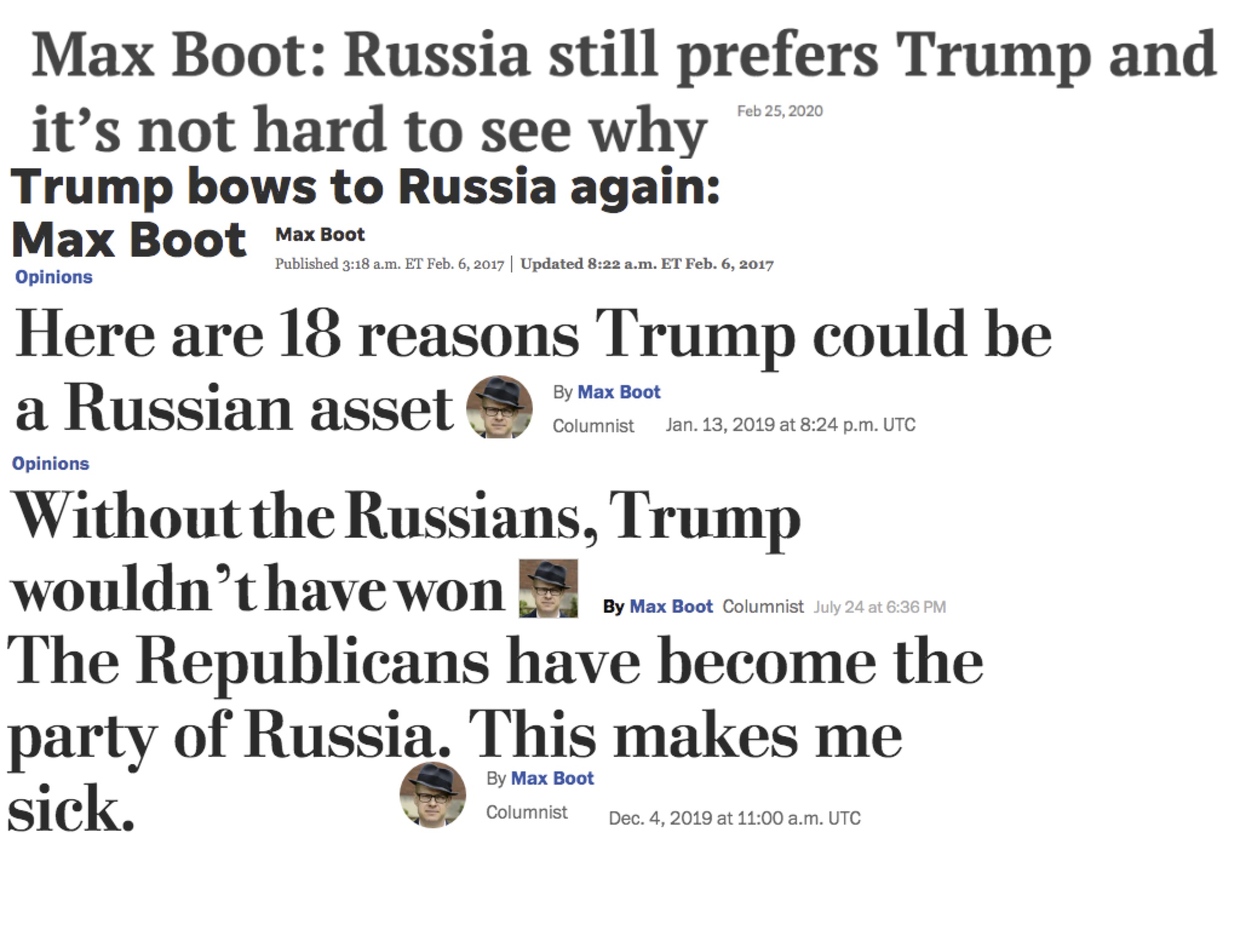

Trump may be the best-known candidate to attract allegations of being ‘Putin’s puppet,’ but he is by no means the first. The Cold War was marked in the US by an ongoing ‘red panic’ that saw politicians accusing their enemies of doing Russia’s bidding, whether as unwitting ‘useful idiots’ or even as Soviet spies. While this pattern died down after the Soviet Union fell and Washington’s focus shifted to fearmongering about Islamic terrorism (which, ironically, they helped create, nurturing the mujahideen to fight the Soviets in Afghanistan), it has returned with a vengeance now that the US’ geopolitical dominance of a unipolar world is no longer a certainty.

Barack Obama

The 2016 election saw allegations of Russian collusion catch fire, but just four years before that, the Moscow Times – an English-language outlet considered sympathetic to the West – published an op-ed straightforwardly titled “Why Putin Wants Obama to Win.” Because Mitt Romney, the Republican billionaire running against Obama, had called Russia the US’ “number one geopolitical foe,” while Putin had called Obama an “honest man who really wants to change much for the better,” Obama was Putin’s choice, the writer reasoned.

Logical enough – the US and Russia were getting along well, so being Putin’s favorite was, for a brief period, not a political death sentence.

ALSO ON RT.COMHear no evil, see no evil, print no evil? MSM warn journalists away from Burisma/Biden info after 'hack' report

But Obama became a “target” of the Russians just a few years later – at least according to cybersecurity firm Area 1, founded by alumni of the NSA and notorious collusion-enthusiasts Crowdstrike. Capitalizing on the media’s burgeoning enthusiasm for Cold War revivalism, Area 1 released a report in May 2017 pinning a series of cyberattacks dating back to Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign on Russia – along with attacks on his 2008 rival, uber-hawk Republican John McCain.

It’s not clear which candidate the Russians were supposed to be boosting with their alleged cyber-shenanigans, especially because the few targets actually named by Area 1 were unaware they had ever been cyber-attacked, and contemporaneous reports of the campaign hacks had blamed China. However, Moscow was clearly supposed to hate Obama. For context, a Newsweek story accompanying the report cited notorious Russophobe Michael McFaul boasting he’s so hated by Moscow that his “colleagues, assistants, and people like that” at Stanford University are attacked “on a fairly regular basis” by Russia even though he’s no longer in government.

That “Putin loves Obama” took just a few years to become “Russians hate Obama, and have always hated Obama” should make it clear just how flimsy the construct of “Russian interference” in US politics really is. With loyalties that shift according to the needs of the political establishment, bogeyman-Russia is easily weaponized against any candidate who comes off as too much of a peacenik, too nationalist, too populist - basically any flavor of divergence from the establishment line of the day.

Jimmy Carter

In this way, Jimmy Carter – a former Georgia governor with no elite political connections – got the “Russian collusion” treatment in 1976 as he sought the nation’s highest office. “Aides say Carter is courted by Russians,” crowed the New York Times, claiming the candidate’s advisers were unsettled by a bevy of “Soviet Embassy officials” making contact, “expressing interest in the Presidential race and implying that they could possibly pursue policies that might influence the outcome.” The article featured much pearl-clutching by “experts on Soviet affairs” claiming they’d never seen anything like this devious outreach.

“I think they have been trying to tell us that they see Presidential politics as an opportunity to interfere in our politics, and that they see an ability to influence the outcome,” an anonymous aide told the Times, which devoted a single line to the fact that the campaign had also been courted by French and British diplomats.

The 1976 election also saw the formation of an “Anyone But Carter” movement among Carter’s Democratic rivals, which attracted several candidates threatened by his outsider status. The relatively-unknown former Georgia governor’s platform included a 5 percent decrease in defense spending and “continu[ing] our friendly relationships with Russia,” and he went on to shock the political establishment by sewing up a hyper-competitive primary against 14 rivals.

After four years in office, however, he’d made some powerful enemies, not least with the Camp David Accords that forced Israel to return the Sinai peninsula to Egypt. Actual, non-Russian foreign meddling is believed to have helped hustle him out the door. Reality is irrelevant to the narrative.

John F. Kennedy

In the same article that painted Carter as the favorite of the Russians, the Times claimed Russia has been meddling in elections since 1960, when “it [was] generally believed by experts in the Russian field” that “the Russians delayed the release of U2 spy pilot Francis Gary Powers to help the electoral chances of John F. Kennedy over Richard M. Nixon.”

The JFK-as-Soviet-favorite line has been especially popular, perhaps because – unlike most “Russian collusion” allegations – there’s some documented proof for this one in the memoirs of former Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev. He claimed it was his government’s decision not to release Powers (along with two other American prisoners from a captured US bomber) that pushed JFK’s candidacy over the line to victory. Confronted with this claim in a meeting with the Soviets, Kennedy, Khrushchev said, laughed and acknowledged the move had helped him. Former Soviet ambassador Oleg Troyanovsky, however, recalls Kennedy denying the “meddling” had had any effect.

Kennedy would later go on to famously clash with Russia over the deployment of missiles to Cuba, bringing the world to the brink of nuclear war, but his subsequent efforts to move the US in the direction of peace with its rival were not appreciated by the political establishment.

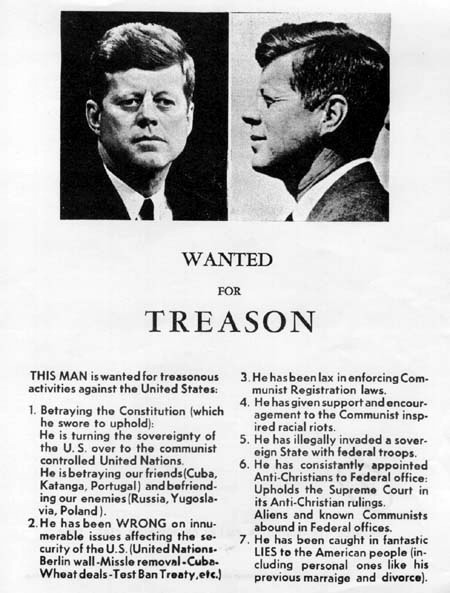

The notorious right-wing John Birch Society would go on to accuse Kennedy of “befriending our enemies” - including Russia - and being “lax on communism,” accusations that would dog him until his assassination, hoping to push him toward a more hawkish stance. While the Birchers’ rabid anticommunist propaganda may seem a far cry from the quasi-respectable accusations found in mainstream media, they’re two sides of the same coin: peace-seeking politicians can expect to be smeared from all directions as agents of a foreign power, because the idea of merely working for peace for its own sake is - to an establishment that has historically profited hugely from war - anathema to their version of America.

Another Kennedy, then-Senator Ted of Massachusetts, actually reached out to the USSR in 1983 seeking Russian assistance for a proposed bid to take on then-president Ronald Reagan. Kennedy, according to a memo written by KGB director Viktor Chebrikov, had proposed getting Communist Party bigwig Yuri Andropov on American TV in a way that would endear him to the American people, and pledged to help the Soviets brush up on their propaganda; in exchange, they were supposed to help him run for president. Kennedy’s overtures were apparently ignored. When the memo was discovered following the USSR’s fall, some on the Right held it up as proof that Moscow had used Democratic “dupes” like Kennedy to influence policy. However, the lack of Russian response to Kennedy’s outreach gives the lie to the “Russian meddling” construct yet again.

ALSO ON RT.COMDemocrats resurrect ‘Russiagate’ to go after both Trump and Bernie Sanders, hide their own election trickery

Al Gore

Former Clinton vice president Al Gore learned the hard way during his 2000 presidential campaign that even toeing the line one’s entire political life is no guarantee against the “Russian collusion” smear when the establishment wants a politician gone. With less than a month to go before the election, he watched Republicans make an “October surprise” out of his work on the Gore-Chernomyrdin Commission - an utterly bland collaboration between the governments of the US and newly-capitalist Russia he’d thought so unimpeachable he’d even brought his Russian counterpart on TV to sing its praises.

Even the LA Times seemed to get whiplash covering the controversy, running the headline “Gore’s Links with Russian Now a Liability.” But in the creative hands of the Bush camp, a publicly-announced arms transaction became “secret deals” requiring investigation, and baseless allegations of embezzling IMF loans made the innocent commission seem like a series of sin-soaked

For an American public that still had a head full of negative propaganda about the Evil Soviets, it wasn’t difficult for the Bush political machine to smear Gore as a corrupt creature of the Kremlin. While he won the popular vote, he fell short in the electoral college and ultimately conceded the election to Bush, avoiding further legal drama over a recount.

Gore was no dove - his platform called for overthrowing Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein, whose nation Clinton’s government starved with sanctions for the better part of a decade. He backed Clinton in the illegal bombing of Yugoslavia in 1999, sneering that anyone critical of the unconstitutional act of war was somehow putting “politics” before the military. While it’s impossible to tell whether Gore would have entered into the disastrous wars that Bush did, he certainly wasn’t a threat to the established order.

If nothing else, the deployment of “Russian ties” smears against even a milquetoast like Gore shows one need not be an iconoclast in order to attract the label. It’s a senseless, opportunistic attack that depends solely on the persuasiveness of the labeler - and how well they can manipulate their intended audience.

The value of the “Russian collusion” bogeyman has thus fluctuated with relations between the US and Russia, falling on hard times after the Berlin Wall came down but gaining a new lease on life thanks to the lack of imagination of the political class. It really found its footing in 2016 and has demanded an outsize share of voters’ attention in the 2020 contest, presenting the very real possibility of a general election that sees one alleged beneficiary of “Russian meddling” face off against another. But the days of requiring proof for such outlandish allegations are long gone, and so is any credibility the smear might once have had. Isn’t half a century of red-baiting enough?

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home