'Every Black Person Deserves To See Themselves This Way'

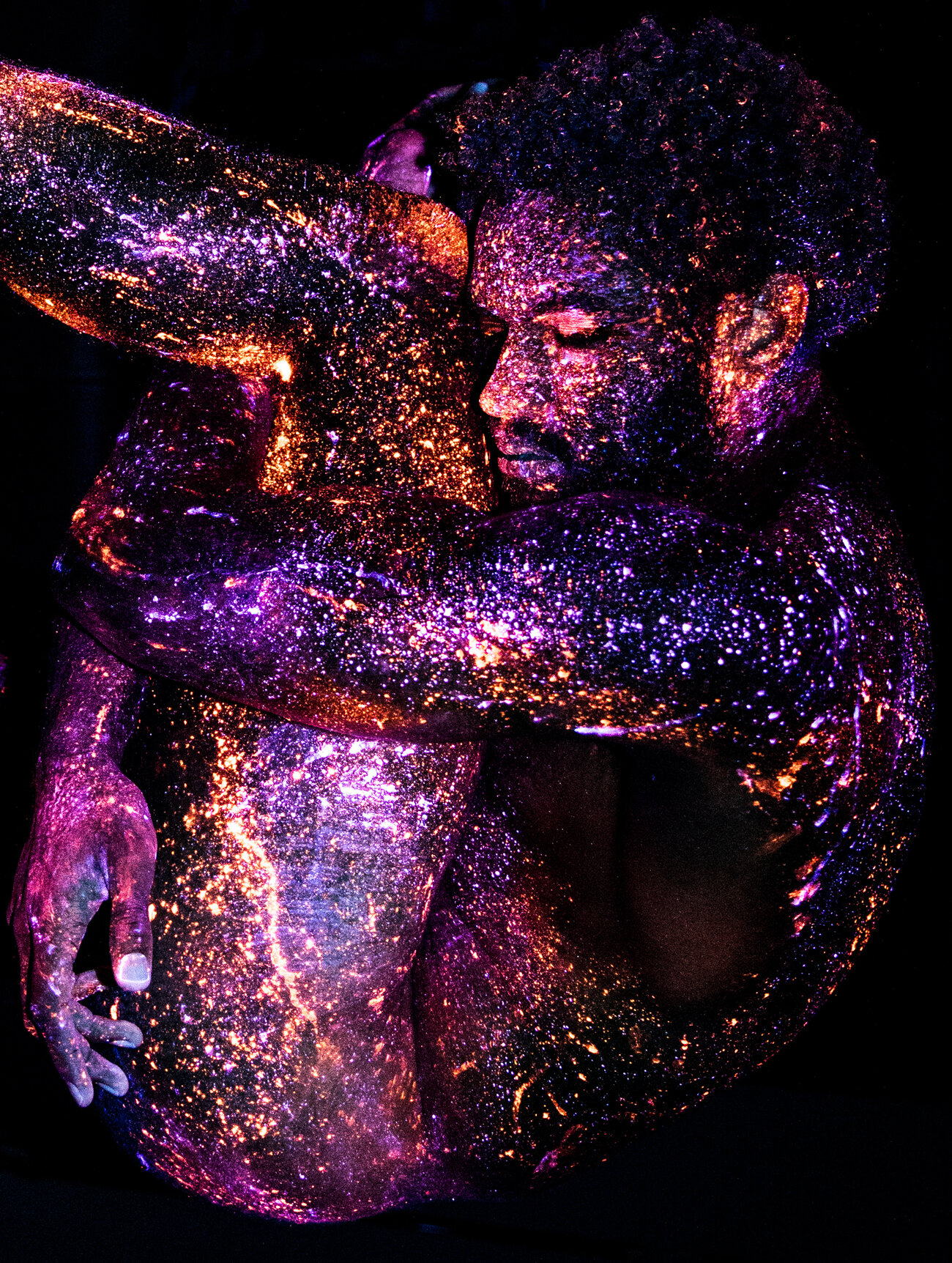

Using fluorescent body paint and ultraviolet light, photographer Mikael Owunna's latest work aims to transform the black body into "the cosmos and eternal." The images evoke celestial beings, magical and otherworldly.

But the concept for the project, Infinite Essence, was sparked by frustration and exhaustion.

The 28-year-old Nigerian-Swedish photographer, who was born in Pittsburgh, Pa., and is based there now, says he grew weary of the barrage of violent, dehumanizing imagery of black people he saw in the media.

"Black people dead and dying. Being gunned down by police officers, drowning and washing up on the shores of the Mediterranean, starving and suffering in award-winning photography. The trope of the black body as a site of death is everywhere," he says in his artist statement.

For Owunna, the final provocation came in 2014: seeing photos of Michael Brown's body lying in the street after he was killed by Darren Wilson, a white police officer in Ferguson, Mo. The image spread across the media, even appearing on the front page of The New York Times.

"If the majority of images that you see of yourself are negative," Owunna says, "if people who look like you are dead or dying or captured in a negative light, how do those images enter your body?"

Owunna wanted to counteract the pain of those photos, to create imagery that showed the black body not as a site of death but as a site of magic.

The name of Owunna's project was inspired by Chinua Achebe's writing on traditional Igbo spirituality, its supreme deity, Chukwu, and the concept of chi, the spirit guide found in every person: "Is chi an infinitesimal manifestation of Chukwu's infinite essence given to each of us separately and uniquely, a single ray from the sun's boundless radiance?" Achebe writes in his essay, "Chi in Igbo Cosmology."

Owunna elaborates.

"Each of our spirits is just one ray of the infinite essence of the sun. And in my photography, [I'm] shooting that UV light, trying to capture that spiritual dimension that we're all on," he says. "How can I capture a piece or fragment or a shadow in that land of magic? That's what I'm grounding the project in and that's what I'm capturing, the spiritual guide for the individual models."

For inspiration, Owunna looked back to a painful season from his past. As a teenager, he felt isolated and bullied for coming out as queer at the Ohio boarding school he attended. Fantasy helped him cope.

"I would catapult myself into these lands of magic that would be captured in Japanese anime or video games or fantasy novels," he says. "So magic, for me, was this world of escape."

(One of Owunna's earlier projects, Limit(less), depicts a diaspora of queer Africans.)

"I went back to the [anime] videos that had inspired me as a child, those videos of magic being formed, and those sparkles coming from the body," he says. His goal became finding a way to embody the eternal — represented by those sparkles — through photography.

He found the solution in fluorescent body paint, the kind people might use for a black light party. The paint is barely visible in normal light, so Owunna had to figure out how to make it show up in his photos.

An engineering student in college, Owunna used that knowledge to augment a camera flash so that it would transmit only ultraviolet light frequencies. That way, when his subjects are covered with the paint and photographed in darkness, the fluorescent colors are illuminated and made visible by the UV light emitted from the flash.

The models look as if they're wrapped in stars.

That the UV light allows us to see these dazzling colors reflects larger themes in his work — as Owunna writes in his artist statement, that "regardless of our experiences of oppression on the physical plane, we are infinite. As infinite as the universe, and the stardust that forms every fiber of our beings."

"Within the visible spectrum we have racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia," Owunna explains. "But if I look in the UV spectrum, which is beyond the comprehension of the human eye, the black body is a site of magic."

At first, Owunna's subjects were friends and family. Now, two years into the project, strangers often contact him, asking to be included.

The process is intimate and requires trust. Owunna lets people choose the colors that speak to them. Then he paints their bodies with the nearly invisible paint, which takes about an hour. In all, the sessions take about five hours.

"It takes so long they get used to being naked in front of me," he says. "It is intimate for sure."

The poses are collaborative and a result of conversation between photographer and model, but Owunna does gravitate toward certain themes. For example with masculine people, he says, he wants to show tenderness, "because masculinity is never really equated with tenderness."

"That's good work for them to be doing emotionally, in terms of opening themselves up to that," he says.

Owunna prints the final images on aluminum, a nod to the West African metallurgy tradition and a tie between the models and their ancestors. The subjects see themselves reflected in the piece, fostering a transgenerational conversation. He also chose metal because though it appears strong, it's fragile and easily bent — a tribute to the lives of black children who have been killed by law enforcement, like Tamir Rice, Aiyana Stanley-Jones, Trayvon Martin and Antwon Rose Jr.

Through this project, Owunna hopes to transform not only the bodies of those he photographs, but of those who see his work.

"I dream of creating exhibition spaces where people can go in, and particularly black people, can go in and feel affirmed in who they are and feel transformed," he says.

"They walk in and their body posture changes," Owunna says. "They take a deeper breath. Their shoulders drop. Their head is a bit higher, and that's something they walk away with."

He recalls the reaction of one of his models when they saw themselves in Owunna's photo: "Wow, my whole life I've dreamed of being adorned with stars, and this is more than I've ever dreamed of. Every black person deserves to see themselves this way."

Mikael Owunna is a photographer based in Pittsburgh, Pa. He was recently awarded a $20,000 grant by the Greater Pittsburgh Arts Council to finish Infinite Essence. See more of Owunna's work on his Instagram.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home