Committee to Protect Journalists condemns Assange’s threatened extradition, but declares he is “not a journalist”

By Oscar Grenfell and Kevin Reed

16 December 2019

The US-based Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) issued a blog post on December 11, attempting to defend the exclusion of Julian Assange from its recently published list of imprisoned journalists.

While condemning the attempt to extradite Assange to the US and prosecute him under the Espionage Act, the post repeats many of the lies and slanders that have been advanced by the corporate press to undermine support for the WikiLeaks founder and legitimise his persecution.

No defender of democratic rights will denounce the CPJ for opposing the threat of Assange’s extradition to the US and the attempt by the US administration of Donald Trump to prosecute him. The organisation’s decision to exclude him from its list of jailed journalists, however, is politically inexcusable and factually untenable.

Assange is perhaps the most famous imprisoned journalist and publisher in the world. He is jailed in conditions of virtual solitary confinement in Britain’s maximum security Belmarsh Prison, a facility which holds convicted murderers and terrorists.

The WikiLeaks founder is not serving a sentence for any crime. Instead, he is being held as a political prisoner by the British authorities, at the behest of the Trump administration. He faces extradition to the US and life imprisonment for publishing the truth about US war crimes in Iraq and Afghanistan, global diplomatic conspiracies and gross abuses of human rights at the American military prison on Guantanamo Bay. After nine years of state persecution and the denial of adequate medical care, Assange’s health has deteriorated to the extent that doctors are warning he may die in prison.

The CPJ’s claims that Assange is undeserving of the title “journalist” also fly in the face of an open letter this month defending Assange, which has been signed by over 800 media workers.

The initiative, supported by world-famous reporters such as John Pilger, stated unambiguously that “Julian Assange has made an outstanding contribution to public interest journalism, transparency and government accountability around the world. He is being singled out and prosecuted for publishing information that should never have been withheld from the public.”

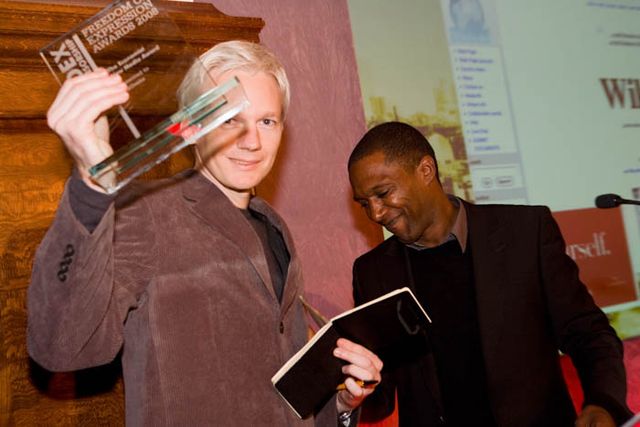

Assange receiving the Economist New Media Award at an Index on Censorship event in 2008

Assange receiving the Economist New Media Award at an Index on Censorship event in 2008

The CPJ’s rejection of these facts, which are evident to anyone who has examined Assange’s record, is inextricably tied to its orientation to the Democratic Party and the corporate press in the United States. The organisation presents as “authoritative journalists,” reporters and editors at publications such as the New York Times, who function as direct conduits of the intelligence agencies, including by slandering Assange and WikiLeaks.

The CPJ is an American independent, non-profit organization based in New York City. Established in 1981, its founding chairman was the CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite. With 40 correspondents around the world, CPJ reports on violations of press freedom and attacks on the rights of journalists “in repressive countries, conflict zones, and established democracies alike.” The organization gives out annual awards to journalists who have endured beatings, threats, intimidation, and prison for reporting the news.

The organisation heavily focuses on the repressive actions of autocratic regimes. Countries that have fallen foul of the US ruling elites, including Russia, China and Iran, feature prominently in its coverage.

The relationship between CPJ’s generally pro-imperialist orientation, and its attitude towards Assange, was exemplified by a statement the organisation issued in June, 2018, hailing Ecuadorian President Lenín Moreno for establishing close relations between his administration and the country’s right-wing corporate press. This was just three months after Moreno had cut off Assange’s communications at Ecuador’s London embassy, where he successfully sought political asylum in 2012, as part of a turn towards closer relations with Washington.

Moreno has since responded to mass protests against his government’s IMF-dictated austerity measures with police repression and dictatorial measures, including moves to abolish press freedom.

In an effort to head off widespread criticism over its refusal to include Assange on the list of jailed journalists, the CPJ Deputy Executive Director Robert Mahoney issued the blog post entitled “For the sake of press freedom, Julian Assange must be defended.”

Mahoney outlined the fact that the CPJ, has, since 2010, warned against an Espionage Act prosecution of Assange. He noted that in that year, WikiLeaks’s publication of leaked documents from the courageous whistleblower Chelsea Manning “unnerved the Washington political and security establishment. Then Vice-President Joe Biden branded Assange a ‘high-tech terrorist’ and Holder said he was considering prosecuting WikiLeaks and Assange under the 1917 Espionage Act.”

Mahoney recalled that the CPJ sent a letter to Obama and his attorney general Eric Holder in 2010 arguing that the use of the World War I-era Espionage Act against Assange “would undermine the right to gather, receive, or publish information of important public interest.”

The CPJ’s 2010 letter made clear that the organisation’s opposition to an Espionage Act prosecution of Assange was bound up with its fears that this would open the door for attacks on “established media.” It stated: “Our concern flows not from an embrace of Assange’s motives and objectives … We believe that such a prosecution could encourage the government to assert legal theories applying equally to all news media, which would be highly dangerous to the public interest. History shows that Congress didn’t intend the law to apply to news reporting.”

Mahoney’s latest statement is a continuation of this line. It seeks to draw a distinction between supposedly legitimate publications, such as the New York Times, and WikiLeaks, with its “practice of dumping huge loads of data on the public without examining the motivations of the leakers,” which supposedly endangers lives.

To legitimise these baseless claims, Mahoney solicited a statement from former New York Times editor Bill Keller, who notoriously declared in 2013 that he regularly exercised the “right not to publish,” based on closed-door discussions with the government.

Keller let loose with a tirade against Assange, declaring: “He gathers information (albeit sometimes by questionable methods), packages it (albeit selectively and with malice) and publishes it (albeit with no sense of responsibility for the consequences, including collateral damage of innocents.) The First Amendment doesn’t just protect people who keep honest company, uphold standards of fairness and publish responsibly.” With defenders such as Keller, who needs enemies?

These claims are a tissue of lies. For all of the assertions that WikiLeaks has jeopardised innocent lives, the US and allied militaries have been compelled to admit that no one has been physically harmed as a result of the organisation’s publications.

In 2010, the New York Times was among those publications that partnered with WikiLeaks in the release of the Afghan war logs. Far from being cavalier about redactions, Australian journalist Mark Davis, who was present at the time, said that Assange alone was responsible for removing hundreds of names from the logs, spanning dozens of man hours. The primary concern of the New York Times, Davis stated, was publishing the material as quickly as possible.

Keller was among the first to refer to Assange as a “source” in 2011. This was a cynical attempt to shield the Times from any prosecution over the 2010 publications by the Obama administration, which it politically supported.

Mahoney gives succour to these self-serving claims, writing: “After extensive research and consideration, CPJ chose not to list Assange as a journalist, in part because his role has just as often been as a source and because WikiLeaks does not generally perform as a news outlet with an editorial process.”

These assertions are refuted by publicly available records of the 2010 releases, for which Assange is being prosecuted, which demonstrate that his relationship with the New York Times, the Guardian and Die Spiegel, was that of a co-publisher. It is further discredited by the dozens of awards for journalism and publishing that Assange has received.

Mahoney’s statement, moreover, contradicts the CPJ’s own definition of journalists “as people who cover news or comment on public affairs through any media—including in print, in photographs, on radio, on television, and online.” Assange fulfills these criteria.

In conclusion, the CPJ post states that “the 18 counts in the DOJ indictment criminalize key reporting practices and the publication of information obtained through them. And the extraterritorial application of the US Espionage Act means that any journalist anywhere in the world could potentially be prosecuted for publishing classified information.

“A successful prosecution would chill whistleblowers and investigative reporting. This is why CPJ opposes Assange’s extradition.”

Why the US government’s prosecution of Assange, if he is not a journalist, would threaten “all journalists,” is a contradiction that the CPJ does not attempt to square.

Its claims that Assange functioned as something other than a legitimate publisher in 2010 are dangerous, and tend to strengthen the case of the Democrats and the Trump administration, who are baying for Assange’s blood.

As American journalist Kevin Gosztola recently noted:

“CPJ has consistently condemned indictments and even rumored indictments against Assange as threats to press freedom. Yet, it is possible that Trump prosecutors may relish the press freedom organization’s decision to exclude Assange. It provides a salient example for the U.S. government’s argument that Assange is not a journalist but a criminal.“If a press freedom organization unanimously supported by U.S. media does not consider Assange a journalist, then perhaps prosecutors will tell a jury this shows there is some ‘truth’ to what Mike Pompeo said when he was CIA director: WikiLeaks is a “non-state hostile intelligence service.”

The CPJ’s exclusion of Assange from the list of imprisoned journalists provoked a significant backlash on social media. That the organisation felt compelled to restate its opposition to the threatened extradition and prosecution of Assange underscores the groundswell of support for the WikiLeaks founder.

The cynical and hypocritical claims of the self-styled “press freedom” organisation, however, underscore the fact that a movement to free Assange, Manning and all imprisoned journalists and whistleblowers must be based on the working class, the social force whose interests are inseparable from the most determined and uncompromising fight for social and democratic rights.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home