Dramatic and engaging, new exhibition Linear celebrates the art in Indigenous science

Professor, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology Sydney

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains images and names of deceased people.

Review: Linear, Powerhouse Museum, Sydney

The value of Australian First Peoples’ scientific knowledge is now being more widely acknowledged.

New exhibition Linear brings artworks into this conversation about the use and adaptation of this knowledge, the impact of industrial technology and the ways new technology can foster our appreciation of place.

The exhibition features the work of more than 16 Indigenous artists and material from the Powerhouse collection, including David Unaipon’s journal and designs.

Country

The most striking feature of this ambitious and disruptive exhibition is a map of Australia, titled Corpus Australis by artist Ngarinyin Elder David Mowaljarlai. The map is a sensationally transformative view of “country”.

The conventional vision of the nation is often marked by the borders of the states and territories. Another familiar map of country is the Aboriginal map of languages and nation groups with borders of rivers, creeks, grasslands and ranges that rivals any map of Europe.

The idea of a nationwide Aboriginal political identity was forged in part through the 1967 referendum campaign and the land and liberation politics of the 1970s; where red, black and yellow captured the people, land and sky.

Mowaljarlai‘s map depicts our shared nation as a body. The gulf country in the north is the lungs. To the south, the Great Australian Bite is the pubic region and Uluru the bellybutton. The rib cage extends from the west to east.

Corpus Australis represents our country as connected through Indigenous and non-Indigenous sites and the sharing of resources and technology over millennia. This is a profound elevation of country to the fore of political debates and discussions.

Scholar Benedict Anderson explained that the modern nation is “imagined”, yet Mowaljarlai reveals its deep connections and patterns interwoven across vast landscapes.

Old ways, new technology

The work of well known figures flanks the entry to the main exhibition space.

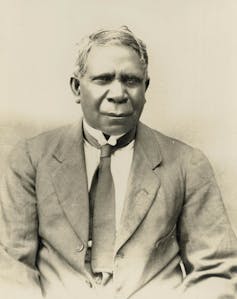

Born in 1872, Unaipon – a celebrated inventor who was Australia’s first published Aboriginal author – appears on our $50 note.

In the exhibition, Unaipon’s work shows how he applied classical knowledge and immense intellectual curiosity to a comparison of the design features that create upward lift for both the boomerang and rotary helicopter blades.

His drawings introduce the viewer to the complexity of Indigenous knowledge: the design of the boomerang, hunting clubs and rituals depicted in bark paintings, and the wap (harpoon) used by activist Murrandoo Yanner whose right to hunt crocodile under Native Title was upheld by the High Court in 1999. Weaving, in the form of three cloaks, stands in for the powerful presence of women welcoming visitors to country.

The works range from photography to weaving, sculpture, digital technology, design and installation art. Artists include Wayne Quilliam, Lorraine Connelly-Northey, Maree Clarke, Mikaela Jade, Nicole Monks, Glenda Nicholls, Lucy Simpson, Bernard Singleton, and Vicki West. They all comment on Indigenous science.

If the map foregrounds the work, the exhibition finds closure in a 17-minute virtual reality film. Collisions by artist and filmmaker Lynette Wallworth, immerses the viewer in the land and pace of Nyarri Nyarri Morgan and the Martu people of the Western Australian desert. The film won the 2017 Emmy Award for Outstanding New Approaches to Documentary.

Wearing Virtual Reality googles, the viewer might be just off Harris Street in Ultimo, but their body sails to the desert country to sit in the back of a Toyota, complete with bumps, muffled sounds and gentle breeze. They can turn around to see the convoy of cars and cloud of red dust that followed behind.

As grass fires ignite, a view from high in the sky shows the mosaic pattern of gentle burning. The fire crackles as it moves along the grass.

On fire

The technology of burning that so shaped this ancient country has returned in some parts of Australia where Aboriginal land has been repossessed. In other parts of the country, fires are raging wild and threaten everything in their path.

Back in the VR world, we sit around the campfire and in front of a big screen that is hitched to the side of the ubiquitous Toyota (bonnet up). We watch footage of the Maralinga bombings. It starts as a mushroom cloud explosion and builds to a fierce storm front that blackens the sky as it races towards us; the bodies of dead kangaroo carcasses hurtle through the air ahead of the blast. All is dead and forlorn. What an unimaginable atrocity to inflict on Martu country.

This is a dramatic and engaging exhibition. As Mowaljarlai’s map announces, it provides a new way of seeing this country: as a body and landscape not of separate nations and language groups – although that is true – but a land with shared rituals, customs and technologies.

There has long been a call for all Australians to embrace this ancient country, rather than fight against it. The Indigenous science and technology in Linear offer us new ways of thinking about the past and future of our now shared land.

Linear in showing at the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney until June 30

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home