Tutor in Philosophy and Sociology, Deakin University

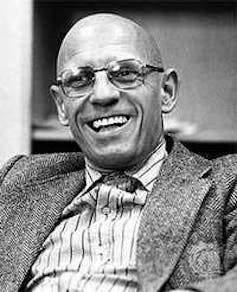

Michel Foucault was one of the most famous thinkers of the late 20th century, achieving celebrity-like status before his untimely death in 1984.

His academic career culminated in a 1970 appointment as “professor of history of systems of thought” at France’s most prestigious university – the College de France. This unusual title was created because of the distinctive nature of Foucault’s work, which straddled disciplines such as philosophy, history, and politics.

Foucault was interested in power and social change. In particular, he studied how these played out as France shifted from a monarchy to democracy via the French revolution.

He believed that we have tended to oversimplify this transition by viewing it as an ongoing and inevitable attainment of “freedom” and “reason”. This, he said, had caused us to misunderstand the way that power operates in modern societies.

For instance, even though the new form of government no longer relied on torture, and public hangings as punishments, it still sought to control people’s bodies — by focusing on their minds.

In his 1975 book Discipline and Punish, Foucault argued that French society had reconfigured punishment through the new “humane” practices of “discipline” and “surveillance”, used in new institutions such as prisons, the mental asylums, schools, workhouses and factories.

These institutions produced obedient citizens who comply with social norms, not simply under threat of corporal punishment, but as a result of their behaviour being constantly sculpted to ensure they fully internalise the dominant beliefs and values.

In Foucault’s view, new “disciplinary” sciences (for instance, criminology, psychiatry, education) aimed to make all “deviance” visible, and thus correctable, in a way that was impossible in the previous social order.

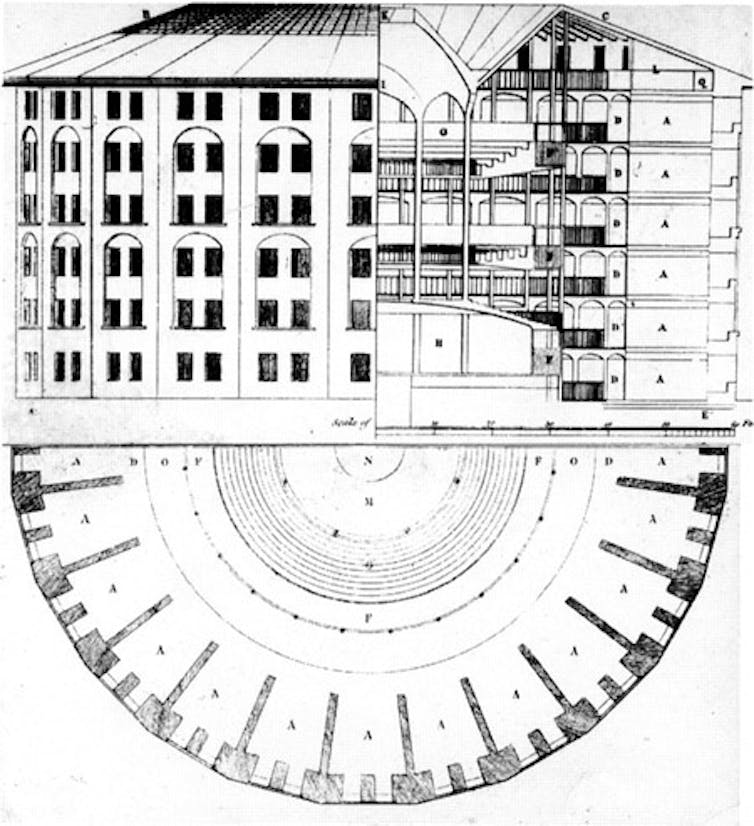

He used English philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s 1787 Panopticon as a metaphor to illustrate his point. This was a circular prison designed to lay each inmate open to the scrutiny of a central watchtower, which was positioned so that individual prisoners could never know when they are being watched.

The prisoners therefore always had to act as though they were being watched. In the wider world, he argued, this resulted in docile people who could fit into the discipline of factories, mental institutions, and the dominant sexual morality.

Foucault argued that people with “mental illnesses” (formerly known as madness) were controlled by relentless efforts at correction to a scientifically determined “norm”.

His 1976 History of Sexuality Volume 1 argued that, rather than talking about deviant acts, scientists talked about deviant types, such as “the pervert” or “the homosexual”, who were in need of concerted efforts of medical intervention and correction.

Power/knowledge

Foucault argued that knowledge and power are intimately bound up. So much so, that that he coined the term “power/knowledge” to point out that one is not separate from the other.

Every exercise of power depends on a scaffold of knowledge that supports it. And claims to knowledge advance the interests and power of certain groups while marginalising others. In practice, this often legitimises the mistreatment of these others in the name of correcting and helping them.

What has made Foucault so appealing to such a broad range of scholars is that he didn’t just look at abstract theories of philosophy or of historical change. Rather, he analysed what was actually said. In his most important works, this included an analysis of texts, images and buildings in order to map how forms of knowledge change.

For example, he argued that sexuality was not simply repressed in the 19th century. Rather, it was widely discussed in an expanding new scientific literature where patients were encouraged to talk about sexual experiences in clinical settings.

With the recent explosion in surveillance cameras as well the role of “big data” we have now well and truly entered the surveillance society. Foucault’s insights on this topic continue to be explored by scholars across the social sciences and humanities.

He has also had a substantial influence on contemporary work in sexuality and gender, sociological studies of mental health institutions and of the medical profession; and in history, politics, cultural studies, and beyond.

An important feature of his theory is that where there is power there is also always resistance. So there are always “sites of resistance”: spaces that hold out the promise for a reconfiguring of power relations in a way that might redress oppressive institutions and practices.

For example, homosexuality has historically been reinterpreted as a “sin”, a “medical pathology”, and now a legitimate “sexuality”, showing how change is possible.

But it is only through a deepened understanding of the origin and structure of our present social order that we will be able to grasp and seize future possibilities for social change.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home