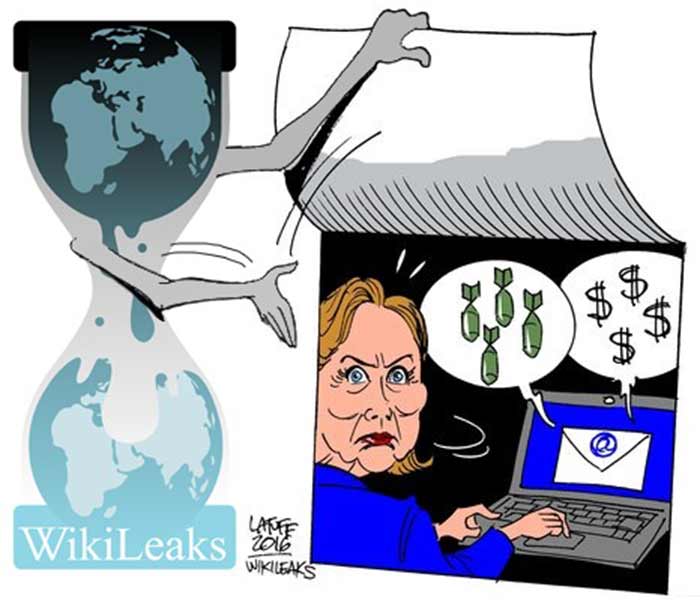

Publishing Stolen Material: WikiLeaks, the DNC and Freedom of Speech

It may well be a finding of some implication should Julian Assange find his way into the beastly glory that is the US justice system. In its efforts to rope in President Donald Trump’s election campaign, Wikileaks, Assange and the Russian Federation for hacking the computers of the Democratic National Committee in 2016, the DNC case was found wanting.

The case presented in the United States District Court of the Southern District of New York was never convincing but remains as aspect of a broader effort to inculpate WikiLeaks and Julian Assange in assisting the Trump campaign triumph. One allegation was key: that “the dissemination of those [hacked] materials furthered the prospect of the Trump Campaign”, a point of assistance the defendants “welcomed”. Claims under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupted Organizations Act and Stored Communications Act, among other statutes, were also advanced.

An important ingredient in the DNC case was that of conspiracy, a notable point given current efforts on the part of the US Justice Department to extradite Assange from the United Kingdom. The elaborate conspiracy was alleged to link the Russian theft of emails and data from the DNC computer system to WikiLeaks and company via dissemination. Effectively, the argument was that stolen materials were disclosed. (Merrily for transparency advocates, the DNC did not contest the veracity of the material, merely the way such material had been obtained.)

Reporters and civil liberty groups rallied. The Knight First Amendment Institute situated at Columbia University, the American Civil Liberties Union and the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, all made submissions backing WikiLeaks’ request for the dismissal of the lawsuit.

The first snag for the DNC team was the Russian Federation. As District Judge John G. Koeltl noted from the outset, the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act rendered the issue of Russia’s legal liability for the pilfering deeds a moot one; the Federation could not be sued in the courts of the United States for acts of state, a point duly acknowledged as reciprocal. Nor had the DNC shown that the case satisfied any exceptions, including that of “commercial activity”. Cyber-attacks, it was accepted, tended to lack the necessary commercial quality.

What then followed was a textbook application of the First Amendment and press freedoms at play. The DNC effort had a smell of desperation; in pursuing WikiLeaks, it had ignored a salient lesson in constitutional history. The good judge was wise to the point, recalling the US Supreme Court decision in New York Times Co. v United States (the “Pentagon Papers” case) upholding “the press’ right to publish information of public concern obtained from documents stolen by a third party.”

The 2001 Supreme Court decision of Bartnicki v Vopper was also added to the judicial mix, one involving the interception by an unknown person of a recorded call between a teachers’ union’s president and its main negotiator. The subsequent airing of the recording by a local radio host did not result in any liability for breaching federal and Pennsylvania wiretapping statutes, despite knowledge that the recording had been obtained illegally. Action on the part of a state “to punish the publication of truthful information seldom can satisfy constitutional standards”.

Koeltl noted that the DNC raised “a number of connections and communications between the defendants and with people loosely connected to the Russian Federation, but at no point does the DNC allege any facts in the Second Amendment Complaint to show that any of the defendants – other than the Russian Federation – participated in the theft of the DNC’s information.” What the DNC was essentially doing was making allegations sound like fact, something of an irritation for Koeltl.

While acknowledging that the DNC’s argument against WikiLeaks might have initially seemed strong, they being “the only defendant – other than the Russian Federation – that is alleged to have published the stolen information”, such an allegation lacked legs.

The Bartnicki case loomed as a heavy precedent: WikiLeaks had played no “role in the theft of the documents and it is undisputed that the stolen materials involve matters of public concern.” It was left to the DNC to distinguish the two cases, something which it tried to do with the concept of the “after-the-fact co-conspirator”. The bridge was alleged to be WikiLeaks’ “coordination to obtain and distribute stolen materials”.

In what seems like an audible sigh coming through the text, Koeltl deemed WikiLeaks’ knowledge that the material was stolen a “constitutionally insignificant” matter and “unpersuasive.” On the other hand, publishing internal communications allowing “the American electorate to look behind a curtain of one of the two major political parties in the United States during a presidential election” was very much deserving of the “strongest protection that the First Amendment offers.”

Even any solicitation of the part of WikiLeaks to obtain such material (prosecutors, take note) was irrelevant. “A person is entitled to publish stolen documents that the publisher requested from a source as long as the publisher did not participate in the theft.”

The logical implication following from punishing individuals and entities for doing so, acknowledged the court, would “render any journalist who publishes an article based on stolen information a co-conspirator in the theft”. Assange and his legal team will be more than a little heartened by this acknowledgment, one that repels efforts to treat WikiLeaks as a hacking rather than publishing enterprise.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. Email: bkampmark@gmail.com

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home