Study traces how the British ruined Western Ghats, one of India’s most unique ecosystems

A biodiversity hotspot, Western Ghats continue to be done in by the British belief that its grasslands were wastelands.

Bengaluru: Over seven decades since Independence, the fragile ecosystem of the Western Ghats continues to suffer at the hands of an abusive British practice meant to tap the biodiversity hotspot for cold, hard cash.

In complete ignorance of the local ecology, India’s erstwhile colonisers planted vast tracts of grasslands with trees meant to yield timber, putting over 150 local flora and fauna species in a precarious position today.

Researchers from the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS), Bengaluru, the University of Leeds, UK, and Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, have conducted a study that seeks to trace the history of the misinformed decisions that led to large-scale damage of the local ecosystem. It was recently published in the journal Biological Conservation.

The Western Ghats are a unique ecosystem where tropical grasslands are interspersed with tropical forests, stretching out as far as the eye can see.

The local tropical forests, known as ‘sholas’, exist in the valleys formed by the montane (high-altitude) grasslands, and have existed so for 35,000 years, much before humans came to the area. The two types have existed side by side because their individual needs keep the other’s overgrowth in check: During the winter, the shola trees don’t do well in the open area exposed to frost, and grasslands do not grow in shady, humid conditions.

The boundaries and extent of the sholas and the montane grasslands grew and shrank for centuries in a stable, dynamic, co-dependent relationship. But colonialism changed all that.

British invasion

When the Nilgiri mountain range, a part of the Western Ghats, was discovered by the British in 1826, the settlers assumed that the bizarre mosaic of grasslands and forests separated by sharp boundaries meant that the locals had transformed an originally mountainous landscape by razing forests.

The settlers then began planting trees in the hills without understanding the different types of plants, ecosystems, or soils. The reasons behind the exercise included beautification, but the primary motive was commercialisation.

As the European settlements increased, the British began to mould the region to fulfil their need for timber to build fires. In the areas near Ooty and Wellington, large-scale deforestation of the sholas ensued. The British forest authorities subsequently introduced strict restrictions to curb the unchecked felling of trees, much to the disadvantage of locals who depended on wood from the sholas for their own sustenance.

However, despite the introduction of contractual tree-cutting, deforestation continued until there was a lack of firewood. The increasing demand for wood for fuel led to the introduction of a new tree species Europeans were familiar with.

Over the course of a century, from the 1820s to the 1930s, more than 40 new invasive and exotic trees were planted. The most common among these were the eucalyptus and the Acacia melanoxylon (Australian Blackwood). However, these did not replace the native shola trees, and instead two lakh of these were planted on 600 acres of the rolling grasslands.

But the need for timber wasn’t solved, and it was felt that more trees were needed. Native shola trees were also planted on the grasslands, but couldn’t be sustained. So, two more species of Acacia were introduced. With the theory gaining ground that the grasslands had bad soil, the trees were planted in patches cleared by felling sholas.

The grasslands were further claimed in the late 19th century for the plantation of tea, coffee and the South American medicinal plant cinchona, whose bark, according to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, was “processed to obtain quinine… used in the treatment of malaria and for fever and pain, and quinidine… used mainly for cardiac rhythmic disorders”.

There was also a surplus of firewood by 1880, and the entire landscape split into blocks of sholas, grasslands and plantations. The British Raj appointed forest officers for each block and the locals were forced to work in the plantations to sustain themselves.

As cinchona from Sri Lanka and Java became more sought-after, the plantations in India began to be planted with the very lucrative tea.

Then, in the quest for better firewood, the large Acacia forests growing on grasslands were felled and replaced with eucalyptus. Then other mountainous trees from across the world like California and Japan started to be planted for timber. When they didn’t grow well, they were again replaced with eucalyptus.

However, the eucalyptus is immensely water thirsty, and soon started affecting reservoirs of water, springs and rivers. As a result, strict checks were imposed on where eucalyptus can be grown.

Slowly, however, the Nilgiris went from promising to disappointing. Large-scale plantations stopped by the turn of the century, and eucalyptus and tea were the only species planted.

After nearly a century, although officials hadn’t given up yet, the general practice of planting exotic trees in an effort to make them grow sustainably came to be considered a failure.

The invasion continues

In the meantime, the new species that did thrive expanded rapidly, taking over the ecosystem. Acacia mearnsii, commonly called wattle, spread rampantly, with its invasiveness a problem to this day.

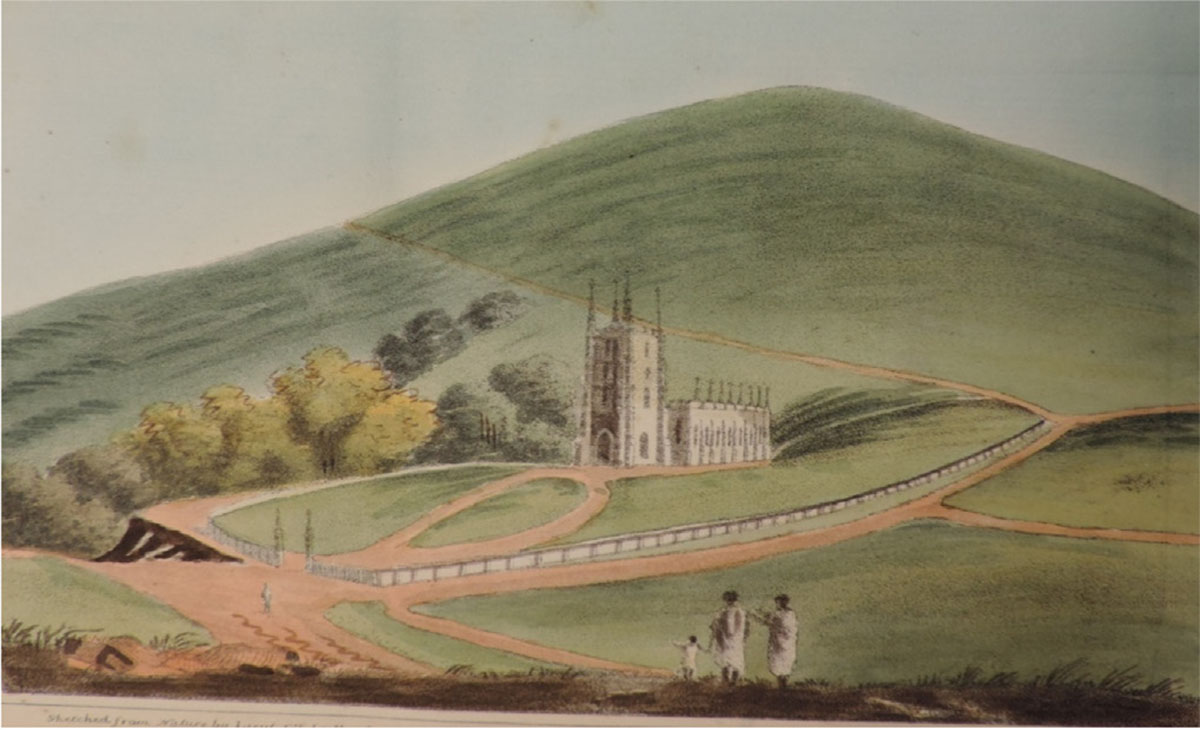

Landscape transformation in Nilgiris. St. Stephen church built in Ooty at the

beginning of colonial settlement. Images show the area around the church at

different time period.

“Colonial encounters with the shola-grasslands began with an appreciation of the aesthetic beauty of the landscapes, but in due course, colonial forestry mostly revolved around utility,” the authors wrote in the study.

They said that although the practice of introducing exotic plants into the landscape stopped, the general mentality that grasslands were barren lands that required transformation didn’t go away.

It was only after Independence that this mentality began to change and studies started revealing that the bi-phase seasonal shola-grassland mosaic systems went back millennia.

Picturesque landscapes of rolling grassy hills with pockets of green shola trees are today replaced with mountains of forests and trees of invasive species such as pine, wattle, and eucalyptus.

These invasive species have adversely affected local plant, animal, and bird populations. The Nilgiri Pipit bird, which thrives in open grasslands, has seen its habitat shrink majorly, causing its existence to be threatened. Over 167 species of rare plants that grow in the region have seen reduction in numbers. The Gaur famously roams in grasslands and has faced increased conflict with humans due to the loss of habitat.

Additionally, the invasive trees have completely messed with the water table, giving rise to several water problems the region faces today. Eucalyptus trees, even when they grow away from bodies of water, tend to spread their roots far and wide. They guzzle water like no other, rapidly lowering the water table. Removing or felling a eucalyptus tree isn’t a solution; a new tree easily sprouts from the leftover bark unless roots are completely uprooted. This has proven to be a consistent problem given the level and expense of labour required.

Pine and other tall trees also grow very tall very rapidly, sucking up a lot of water in the process. This further shortens the supply of water to the locals.

In 2014, the Madras High Court issued an order to fell the invasive plant species to restore the area’s ecological balance. But a year earlier, in 2013, the Tamil Nadu government had declared just over 600 square kilometres of land planted with these invasive species the Kodaikanal Wildlife Sanctuary. A 1996 Supreme Court order that bans the felling of trees makes the 2014 order more complicated, preventing any action from taking place.

To make matters worse, satellite images reveal that, between 1993 and 2014, the forest department continued to plant invasive plants in the region.

Grasslands went from being the most abundant type of vegetation in Palani, Tamil Nadu, to the rarest. It appears that, in popular perception and especially among policymakers, the notion that grasslands and savannas are degraded ecosystems that require restoration through planting invasive trees remains common.

https://theprint.in/science/study-traces-how-the-british-ruined-western-ghats-one-of-indias-most-unique-ecosystems/147041/?fbclid=IwAR1wuGQybOGyP-sG430XfCWbGHokBPBvQEBR9XXvhtR9tKMFoVT2W8BrgvM

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home