How is hawkish fanaticism whipped up at home? One exhibition offers insight.

A World War II propaganda poster. Public domain.

Jim Harrison’s novella Legends of the Fall, made famous by the 1994 film starring Brad Pitt and Anthony Hopkins, recounts the tragedies that ensue when the three sons of an aristocratic Montana rancher ride north in 1914 to enlist in the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Given that an estimated 17 percent of Montana’s young men volunteered or were conscripted to fight in the bloody trenches of France and Belgium during World War I, Harrison drew from the real history of a young state that was largely enthusiastic about that war.

Such ardor can, however, have a darker side. In 1918, Montana passed the nation’s harshest sedition law, which criminalized criticism of the war effort and served as a model for the federal government’s own Sedition Act enacted a few months later. Although the war was nearly over when it was passed, 200 Montanans, many of them German immigrants beset by a nationwide anti-German hysteria, were charged and 79 were convicted for being vocal in their opposition to the war.

Walking through a new exhibition at the de Young Museum in San Francisco entitled Weapons of Mass Seduction, one gets more insight into how such fanaticism was whipped up. Drawn from the extensive collection of the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts of the San Francisco Fine Arts Museums, the exhibition chronicles martial propaganda from countries on both sides of the two world wars. Visitors see French recruiting posters, German calls to arms, and copies of sheet music for cheery Great War ditties meant to be sung by family and friends around the American parlor piano. Posters, films, leaflets, and other items in this well-curated exhibition highlight the ways in which tools being developed by burgeoning advertising and entertainment industries were pressed into service to shape public sentiment and gin up popular enthusiasm.

The iconic Army recruiting image of a finger-pointing Uncle Sam saying “I Want YOU” greets the visitor entering the gallery. Recruitment, however, plays a surprisingly small role in the exhibition, perhaps because of the dominant role that conscription played in both world wars. The Uncle Sam poster made its recruiting debut in 1917, the same year that the draft was instituted.

Much messaging was instead aimed at affecting morale on the home front and at changing domestic habits to avoid waste and stretch resources. A cluster of posters records the push for Americans to garden, can their own food, eat less meat, and collect and turn in everything from scrap iron to rags to kitchen drippings. Multimedia exhibitions seem to be the thing these days, and visitors here are treated to a collection of animated short films produced for the U.S. government by Walt Disney during World War II. One features Minnie Mouse in the kitchen—when suddenly a stern voiceover stops her from putting leftover bacon grease into Pluto’s dog dish. Initially angry at losing his treat, Pluto ends by proudly carrying a bucketload of grease to the local butcher shop, where such renderings are collected to make bombs that, as the viewer is vividly shown, will be dropped on Hitler’s Germany.

A curatorial note informs us that, far from merely contributing a bit piece here and there, Disney Productions devoted more than 90 percent of its output to the war effort between 1942 and 1945. Disney animators and artists created internal training films for the military, propaganda posters, patriotic comic books, and even war bond certificates featuring Disney characters. Mickey Mouse and other such figures became so associated with America’s war effort that they were employed in German and Japanese propaganda as sinister enemy figures. Mickey’s likeness is even found on one of the Japanese “propaganda kimonos” that provide an unexpected caesura at the exhibition’s midpoint.

Because the exhibition is arranged by subject, one sees commonalities: an Allied poster from World War I might be found next to a similarly themed one from the Axis side in the second war. From the perspective of the universality of wartime imperatives, this makes sense. Obscured, however, is the subtler record of increasingly sophisticated techniques that a more chronological arrangement might have shown. A Charlie Chaplin silent film from World War I, in which Chaplin bonks the Kaiser on the head and then hawks Liberty Bonds, may have been cutting-edge persuasion at the time it was made. If it had been allowed to stand next to, rather than across the room from, the highly advanced cinematography of a World War II Army film portraying GIs listening to Japanese radio broadcasts from “Tokyo Rose” (multilayered propaganda about propaganda), the contrast would have been striking.

The posters from World War II likewise are subtler in their messaging than their predecessors, and hence perhaps more effective, even though the artwork from the first war is generally superior. One wonders how much of this more nuanced presentation was due to advances in advertising techniques in the intervening 25 years and how much to the fact that war propagandists knew how badly they had overreached during World War I. A fascinating concluding display tells of Columbia University’s Institute for Propaganda Analysis, formed in 1937 to study and disseminate information about the techniques used in modern propaganda. It emerged in part from public awareness of foreign propaganda efforts to influence America’s decision on whether to enter World War I.

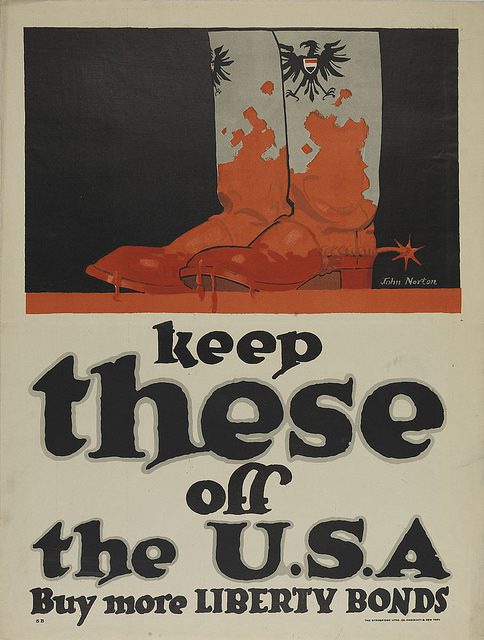

World War I-era poster urging Americans to buy more Liberty Bonds to keep bloody German boots off of American soil. Artist: John Norton, ca. 1917-1919. (public domain)

This November will mark the 100th anniversary of the end of “the war to end all wars,” and at a century’s remove it is Allied propaganda from that particular conflict that is perhaps most intriguing. One poster features the “mark of the Hun” (a bloody handprint), helpfully telling us that Liberty Bonds are the antidote. Another continues the Liberty Bond theme by portraying a ghoulish “Hun” with bloody hands holding a dripping bayonet and who is peering over the horizon with a none-too-large expanse of water separating this black and barely human creature from the vulnerable viewer. A third exhorts the viewer to “Keep These off the USA” by buying yet more Liberty Bonds; “these” are blood-soaked boots and spurs bearing the imperial German eagle.

♦♦♦

A certain amount of dehumanizing of the enemy is a natural part of any war effort, but Allied propaganda against the Germans in World War I is particularly striking in its crudity and ferocity, especially since one would have a hard time finding Americans today capable of explaining, even in the broadest of terms, exactly what our country was doing in that war. One of the more visually arresting World War I posters in the exhibition portrays a slumbering, rosy-cheeked, and classically-garbed female personification of America. “Wake Up, America!” the poster admonishes. “Civilization Calls Every Man, Woman, and Child!” No arguing with that.

Against such a backdrop some stories from that time come into focus. One involves Hermann Bausch, a Montana farmer who was dragged from his home and nearly lynched in 1918 when neighbors surrounded his house and demanded that he buy Liberty Bonds to prove his loyalty to the United States. He survived the day but only because he ended up in the state penitentiary for sedition. The Montana connection was unexpectedly brought to mind during the exhibition because of a passing curatorial note about Hollywood’s involvement in the war effort: “Some in US Congress believed film propaganda to be a threat to democracy. In 1941, Senator Burton K. Wheeler wrote to Paramount News that ‘the motion picture industry is carrying on a violent propaganda campaign intending to incite the American people [to war]…’”

Although not identified as such, Wheeler was a Montanan who first became famous as a U.S. attorney in Butte who refused to indict anyone under the national Sedition Act during World War I. He later became a four-term U.S. senator and steadfast opponent of American involvement in World War II until Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. But it’s noteworthy that Montana produced strong antiwar leaders such as Wheeler and Jeanette Rankin (the only member of Congress to vote against entering both world wars) while also being a hotbed of patriotic war fervor. Such skepticism about foreign conflicts, mixed with patriotic support for the troops, is characteristic even today of much of Middle America.

At such an exhibition, one expects to see some links with contemporary America, in which the drums of war are always within earshot. But there are substantial differences. With limitless federal borrowing, the government no longer needs to hawk Liberty Bonds to finance foreign adventurism. Military actions are kept just small enough to stay within the limits of a volunteer force, so conscription need not be justified in the public eye. Social pressures and secular pieties now drive recycling and self-rationing in the service of climate change and veganism. In short, governments today don’t perceive a need to mobilize broad public support before waging war.

They just do it.

Weapons of Mass Seduction runs through October 7 at the de Young Museum in San Francisco.

Bradley Anderson writes from San Francisco, California.

https://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/the-dark-side-of-war-propaganda/

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home