Walker Percy and the Gift of Influence

Far from atomized, our lives are indelibly impacted by others, as Percy well understood.

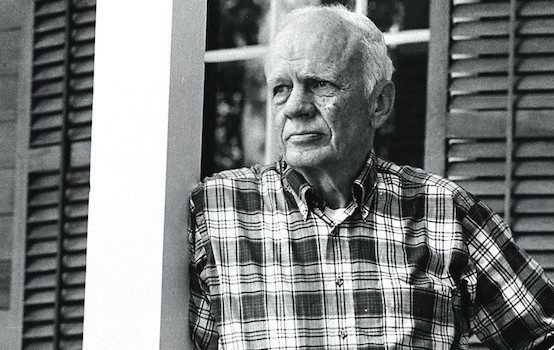

Walker Percy (Photo courtesy Christopher R. Harris, who owns the copyright)

It is an unspoken rule in some circles that all authentic people wish to escape the inheritance offered by their forebears. In The Anxiety of Influence, Harold Bloom gives voice to this hope by claiming that no poet intends to follow patterns set by prior masters, arguing that only “weak” writers would do this. The strong seek a new path. The idea that one can be genuinely original particularly haunts many artists and writers.

This Nietzschean aspiration for self-creation is probably responsible for a good deal of misery and anxiety among the creative class. The desire for novelty and progress in art, music, scholarship, and so many other fields of life fosters an attitude that undermines our ability to care for culture; it also causes incredible mischief in politics and law.

But perhaps most importantly, the idea that we can be autonomous self-creators defies the lives we live together. We are born of mothers and fathers; our minds and hearts are cultivated by family, friends, and teachers; and an honest look at any professional life will reveal a web of influences and debts great and small.

Human beings need not pretend they live with such unbounded freedom. This was one of Walker Percy’s most important lessons, and this insight is among many that Jessica Hooten Wilson draws out to great effect. Wilson is a dedicated literary detective, and in her two most recent books, she offers readers a window into Percy’s mind, and especially into the influences that he willingly embraced as he honed his craft as a writer.

In Walker Percy, Fyodor Dostoevsky, and the Search for Influence (2017), Wilson systematically uncovers how Percy turned to the Russian master throughout his works. In addition to offering perceptive readings of Percy on his own terms, and discovering surprising connections between the two authors, Wilson also recovers a saner view of influence in human life against Bloom’s romantic notions of authorial independence. She argues that instead of a haunting anxiety concerning his influences, Percy adopted widely and freely from his favorite thinkers. He was a self-professed “thief” of philosopher C.S. Peirce and an avid reader of Camus, Kierkegaard, and many others, but Wilson convincingly demonstrates that it was Dostoevsky that Percy imitated most deeply.

Tracing out the links between authors requires a profound degree of detective work. Wilson draws on letters and notes in archives at Chapel Hill and Princeton, and deploys these alongside close readings of Percy’s essays and novels, as well as Dostoevsky’s writings. In reconstructing the ways that Percy adopted Dostoevsky as a mentor, Wilson articulates her own theory of how we should approach the idea of influence. She faces an uphill battle here with the scholarly community, because of the sheer unfashionability of studying how one writer shapes another: “Influence studies are unpopular because, to the modern mind, they disenfranchise writers of originality.”

Wilson—in a very Percyean move—inverts the normal assumptions about this, arguing it is a sign of Percy’s humility as a thinker that he turned to a master. More than this, he accepted the profound influence of his life-long friend Shelby Foote in this matter, as it was Foote, the honorable Southern worshipper of art, who encouraged Percy to find his voice as a specifically Christian novelist.

Percy’s adoption of Dostoevsky did not proceed in a straight line. Wilson describes Percy’s first, unpublished attempts at crafting stories as failures because they relied “more on ideas than on stories, creating incorporeal characters that inhabit blank spaces, not taking action, making choices, or engaging with one another.” What Percy ultimately learned was that what Wilson calls an “incarnational aesthetic” offered tremendous possibilities as a path to renewing our understanding of reality, and here Percy’s debt to Dostoevsky is clearest.

These stories would be incarnational in the sense that they would place characters in a predicament with not just material but also spiritual dimensions, and show them to be “wayfarers or pilgrims, unsettled in this home that is not their home.” Wilson argues that the most significant aspect of this aesthetic is that it “showcases a world of contradiction in which horror often accompanies beauty.”

In Love in the Ruins, Percy’s comic apocalypse, secularization and the ambition to remake and perfect the world proceed together. Wilson emphasizes that for both Percy and Dostoevsky, this kind of cultural change isn’t an accident: both understand that man never does without religion. His worship simply changes form. But amidst this, both authors depict characters who are torn between body and soul, and can find no way to reunite what had been rent asunder. This condition has a name, the Lucifer syndrome:

Suffering from the Lucifer syndrome, a human being would lose his or her humanity and either exalt the self as a god or surrender to the lower animalistic impulses. Once the Lucifer syndrome has begun, it acts as a contagion: the choice for escape is between suicide or salvation.

The Search for Influence offers a pointed reminder that the political and social crises of the present day have much deeper theological causes. Wilson brings this together in a powerful conclusion that challenges readers to return to imitation as a way of being rather than embracing the anxiety Bloom evoked about influence. She explains:

God’s death is a prerequisite for the freedom of the poet. While He remains, poets are bound on both sides by impossible chains, the commands, in Bloom’s words, to imitate God while not to presume godlikeness. The two sanctions are at odds only when one misunderstands God’s nature and thus the word “imitation.”

It is no accident that Bloom praises Milton’s Satan, she observes, but we can reclaim a better path, one trod by great writers before us.

Wilson’s most recent book, Reading Walker Percy’s Novels (2018), offers a very different kind of experience after the Search for Influence. Here, Wilson’s intention is to write a serious introduction to the practice of closely reading Percy’s works and becoming alert to the many possibilities he raises.

While Wilson aims at a general audience (she specifically mentions the attendees at the great Walker Percy Weekend), this is also a text that scholars can profitably read because it ties together so many different threads across Percy’s writings.

While she is a master of Percy’s novels, the brief appendix on Lost in the Cosmos offers a particularly adept introduction to the book’s place in Percy’s thought as a whole, its often-savage critiques of every trend in our life, the theory of the human person masquerading as a philosophy of language, and the Lucifer syndrome manifests in the American tendencies toward theory and consumption.

We’re apt to think that philosophers, scientists, and other experts have their lives figured out, but Wilson offers us Percy’s reminder that no matter how transcendent the theory, “no one can ride a high horse into eternity,” and all too often, “the great geniuses of the world needed somebody to love.” The challenge, she notes, is that “you can’t hold someone’s hand if you’re floating ten feet above them.”

In presentations of each novel, she also artfully places Percy’s novels into conversation with his many essays and lectures, as well as some of the wider influences he drew upon. She makes excellent use of interviews as well that help illuminate Percy’s intentions as a writer.

The book offers many comparisons between the novels that offer important food for thought. In discussing The Last Gentleman, Wilson observes that the difference between the novel’s protagonist Will Barrett and Percy’s first successful creation The Moviegoer’s Binx Bolling is that while “Binx’s search was profoundly negative—how to alleviate despair and malaise—Barrett’s desire is directed toward a more positive goal: how to be happy.” Both characters embark upon search, and Wilson suggests that reading about them with our lives own search in mind can alert us to signs in our own lives.

I was particularly struck by her chapter on Lancelot, Percy’s journey into the heart of evil. She offers this summary of what Percy accomplishes in the book:

Like one of Edgar Allan Poe’s mystery stories, Lancelot is horrific, surreal, and full of murder and seduction…. Lancelot is explicitly a liar. Moreover, he is a murderer and a prisoner in a Center for Aberrant Behavior; he is categorically insane…. We are not inside the head of the possessed, receiving first-hand knowledge of the demonic, and listening to someone who desires to end the world.

One of Percy’s greatest accomplishments—and to which Wilson does justice—is that he leads his readers into a confrontation with the disorder in their own hearts. In Lancelot, he does this by drawing the reader into conversation with a convincing apostle of a violent “new order,” one that he suggests is closer than any of us quite realize. This book deserved the fresh eyes Wilson gave it, particularly in our fraught times.

People who struggle to escape any trace of influence in their lives fail to notice something critical. Influence is omnipresent, and while we can try to erase the traces of other people’s effects on our lives and thought, we nearly always do so in the name of ideology. This all too easily places us in unwitting service of alien powers—transcending abstractions of race, class, gender, structure, and power. Percy gives us the tools to ward off those demons.

Brian A. Smith, managing editor of Law and Liberty, is author of Walker Percy and the Politics of the Wayfarer.

http://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/walker-percy-and-the-gift-of-influence/

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home