The Humanitarian Trap

TAC looks back on one of the most common—and insidious—rationales for foreign intervention.

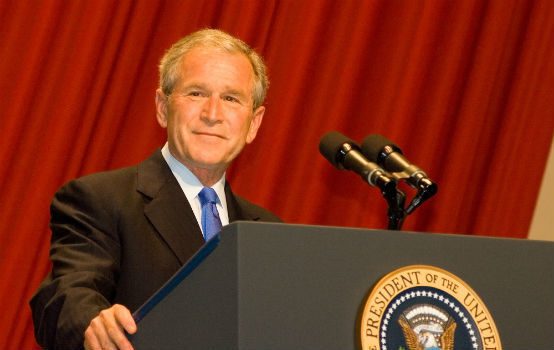

Credit: Joseph August/Shutterstock

This magazine was born, as we indulge ourselves in noting in this anniversary issue, during the national ferment surrounding George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq. And, as noted also, we have never wavered in viewing that war as a tragic mistake.

This article appears in the May/June 2018 issue.

We’ve had plenty of incentive to project our views on the subject these many years because the questions surrounding the war never seem to get resolved in the national consciousness. We debate endlessly how the government could have been so wrong about Saddam Hussein’s weapons of mass destruction. We argue over whether the ongoing chaos of the region stems from the invasion itself or Barack Obama’s decision to pull from Iraq the last troops left by Bush (who, incidentally, had agreed to the withdrawal timetable executed by Obama). We’re still squabbling about the essence and actual impact of Bush’s 2007 troop “surge.”

But one element of the issue never seems to get adequately aired—the matter of whether humanitarian interventionism ever really makes much sense for a government whose first responsibility is to its citizens. Much of the lingering discussion on Iraq focuses on the second Bush’s insistence that Saddam had to be eliminated because of his WMD and ominous ties to al Qaeda terrorists (both untrue). But he also hailed the great good works America would perform through his invasion. The humanitarian impulse was on full display in the war’s runup.

Perhaps that isn’t surprising since that impulse has never been far from the surface when America has sent troops into the world. The country’s first great imperialist president, William McKinley, loved to talk about America’s civilizing mission in the Philippines—even as he sent in more troops to quash the indigenous folk who didn’t view America’s colonial leaders as liberators.

But fundamentally America’s overseas adventures had a primary rationale of national interest. Everyone knew America took the Philippines to exploit its untapped resources, project military power into Asia, obtain coaling stations for the country’s burgeoning navy, prevent Germany or Japan from getting those islands, and generally to make America great. The humanitarian aspect was always secondary.

Now it is primary. Americans see agonizing video of struggling children following chemical weapons attacks, and the nation’s anguished leadership rushes to a military response before there’s been any chance of determining even provisionally who actually perpetrated the atrocity. The nation applauds. Hardly any debate ensues.

But there should be debates. As devastating as it is to see these cruelties, the reality is that there is far more such cruelty around the world than America could ever begin to ameliorate. That inevitably leads to hypocrisy. Why is attacking Bashar al-Assad’s military an absolute moral imperative while there’s nary a fidget of discomfort when America helps Saudi Arabia starve children in Yemen? Why is ethnic cleansing atrocious when the Serbs do it to Muslims but not when Muslims or Croats do it to Serbs? Why did starving Somalis deserve an American military intervention in 1992-93 but not the starving Sudanese or Congolese in subsequent years?

Humanitarian interventionism is an understandable impulse, driven by good intentions. But good intentions got 19 U.S. servicemen killed in the dusty streets of Mogadishu in 1993 for a failed mission. Good intentions led to Libya’s destabilization, with dire consequences for the region and America’s fight against Islamist radicalism. Good intentions contributed to the overthrow of an elected president in Ukraine and a subsequent civil war that could draw the United States and Russia into an ominous confrontation.

Interventions based on national interest justify whatever American blood is expended in their behalf. Interventions based on gauzy humanitarian notions? Not so much.

http://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/the-humanitarian-trap/

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home