1944 Korematsu opinion on Japanese American internment is tossed out

In its ruling Tuesday upholding President Trump’s controversial travel ban, the U.S. Supreme Court added a secondary eye-popping decision: It overruled its 1944 opinion that validated the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II — calling it unconstitutional.

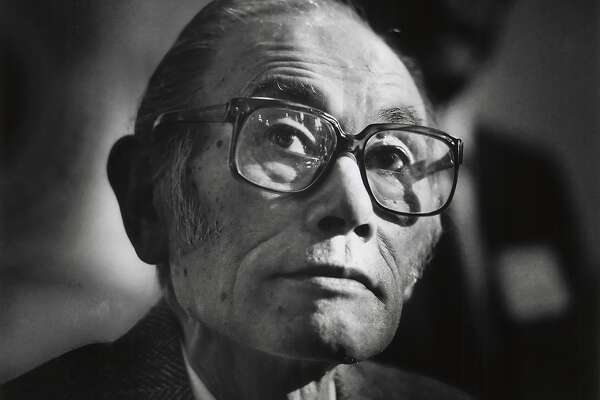

The 74-year-old internment case was based on a lawsuit filed by Fred Korematsu, an Oakland-born man who challenged President Franklin Roosevelt’s executive order that led to the eviction and internment of 120,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans from the West Coast following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. At the time, the U.S. Supreme Court called the imprisonment of citizens constitutional because of military urgency and the need to take “proper security measures.”

On Tuesday, Chief Justice John Roberts, rejected arguments that likened Trump’s travel ban on mostly Muslim-majority countries to the internment of Japanese Americans. Roberts argued in the majority opinion that Trump’s policy is constitutional because it was based on national security concerns rather than race or religion.

He added: “The dissent’s reference to Korematsu, however, affords this Court the opportunity to make express what is already obvious: Korematsu was gravely wrong the day it was decided, has been overruled in the court of history, and — to be clear — ‘has no place in law under the Constitution.’”

Justice Sonia Sotomayor, in her dissent, wrote, “This formal repudiation of a shameful precedent is laudable and long overdue. But it does not make the majority’s decision here acceptable or right. By blindly accepting the Government’s misguided invitation to sanction a discriminatory policy motivated by animosity toward a disfavored group, all in the name of a superficial claim of national security, the Court redeploys the same dangerous logic underlying Korematsu.”

In the Bay Area, critics seized on the irony of the double decision.

The court both acknowledged a historic mistake and then repeated it, said Tom Ikeda, executive director of the Densho Institute, which documents the stories of those interned during World War II.

“They are saying the same thing today — that these people are dangerous and we have to give the president deference because he knows more,” he said. “As a Japanese American I’m really disappointed that the court hasn’t learned from history and the past.”

The Korematsu case has long been considered a judicial stain on the country’s history.

In San Francisco, all persons of Japanese ancestry were told to report to the Reception Center by April 7, 1942, with bedding, toiletries, essential personal effects and “sufficient knives, forks, spoons, plates, bowls and cups for each member of the family.”

Korematsu refused to leave, undergoing cosmetic surgery on his eyes to hide his identity, but he was ultimately arrested in San Leandro and convicted of violating the order.

Decades later, researchers discovered the government suppressed intelligence reports showing Japanese Americans had not committed crimes, nor were they a threat to the country, raising questions about the real motivation behind the mass internment.

The U.S. District Court in San Francisco cleared Korematsu’s conviction in 1983, but the Supreme Court ruling remained on the books, without a similar case of mass incarceration to raise the issue again, said Eric Muller, law professor for the University of North Carolina School of Law.

“This question of whether Korematsu is or is not good law has been kicking around for several decades now,” he said. “It looks as though the Supreme Court decided finally to try to put the question to rest.”

A separate and similar U.S. Supreme Court ruling that preceded Korematsu, however, has never been overturned, a decision that upheld a curfew of Japanese Americans on the same grounds as the internment, Muller said.

In Hirabayashi vs. United States, the ruling continues to serve as legal precedent, with Department of Defense lawyers recently citing the case to prevent a Guantanamo Bay detainee from publicly sharing artwork. Aki Okuno, 92, who spent more than two years in an internment camp in Arizona, sees similarities to the camps in Trump’s policies, which she said assign blame and suspicion on groups of people.

“That is the thing that is definitely un-American,” she said.

While the Supreme Court has reversed the Korematsu decision, she fears too much has been forgotten.

“It’s a blot on American history like this current situation,” she said. “The whole world is looking at us aghast.”

Jill Tucker is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: jtucker@sfchronicle.com

Twitter: @jilltucker

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home