If Catalonia, Why Not California, Texas, or New England?

Catalonia, in the southeastern corner of Spain, is in the news.[Catalonia Government Declares Overwhelming Vote for Independence, by Raphael Minder, NYT, Oct 6, 2017] I was there once, back in my salad days, on my way to a camping vacation down the coast at a sleepy little whitewashed village named Oropesa del Mar, now all built up with tower blocks and tourist hotels.

Catalonia, in the southeastern corner of Spain, is in the news.[Catalonia Government Declares Overwhelming Vote for Independence, by Raphael Minder, NYT, Oct 6, 2017] I was there once, back in my salad days, on my way to a camping vacation down the coast at a sleepy little whitewashed village named Oropesa del Mar, now all built up with tower blocks and tourist hotels.

“Sleepy” was a pretty good descriptor for Spain itself in the mid-1960s, after 25 years of deep clerico-conservatism under the rule of Generalissimo Francisco Franco. We flew into Barcelona and stayed one day there. It was terrifically hot. There was not much traffic and the buildings all seemed about two hundred years old. People moved at a slow walking pace, except for the couple of hours around midday when they didn’t move at all.

Perhaps, I remarked to my companion, it might not be entirely coincidence that “Catalonia” differs by only one letter from “catatonia.”

Changing trains some way down the line we got stuck in a railroad waiting room on the wall of which was pasted an ancient fading poster headed Proclamación Real—”Royal Proclamation.” Spain was an on-again, off-again monarchy through the 19th and 20th centuries. Right now it’s “on”—present-day Spain is a monarchy. That’s only been the case since 1975, though. When I was there in 19 65, Spain was not a monarchy. It hadn’t been one since 1931.

So I, standing there in that lonesome railroad halt in 1965, was looking at a pasted-up Royal Proclamation at least 34 years old.

Rather than engage with the particular issue at hand, I shall make some general observations about nationalism, as in Spain, and sub-nationalism, as in Catatonia … sorry, Catalonia, and trans-nationalism.

The great classic Chinese novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms opens with a sentence that any literate Chinese person can quote to you: 話說天下大勢, 分久必合, 合久必分 — “It has been said of all under Heaven that what was long divided must unite, what was long united must divide.”

As well as being a fair summary of four thousand years of Chinese history, that’s not a bad guide to history at large. Nations come together and merge; empires form then disintegrate.

Yes, there are those big historical tides ebbing and flowing. But we can form preferences related to our own time and place. Mine are nationalist, with a seasoning of skepticism.

Nationalism isn’t hard to understand. People want to live among and be governed by other people mostly like themselves, with the same language and shared history, not by foreigners in some distant city who don’t understand them.

It is of course the case that our co-ethnics may be crazy beasts — North Korea‘s a nation; Khmer Rouge Cambodia was a nation — while the foreigners in that distant city might be benign and wise, or at any rate not life-threatening. The Middle East under the Ottoman Empire was not an exemplar of peace and justice, but it doesn’t compare badly with today’s Middle East.

It is of course the case that our co-ethnics may be crazy beasts — North Korea‘s a nation; Khmer Rouge Cambodia was a nation — while the foreigners in that distant city might be benign and wise, or at any rate not life-threatening. The Middle East under the Ottoman Empire was not an exemplar of peace and justice, but it doesn’t compare badly with today’s Middle East.

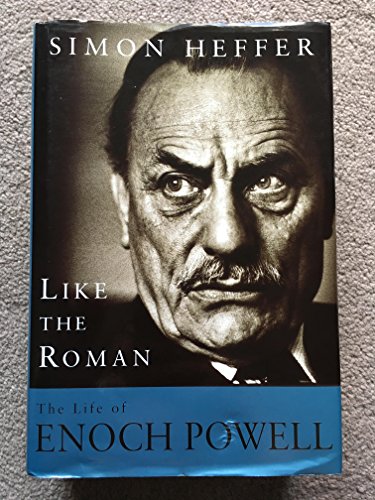

The great British national conservative Enoch Powell, who fifty years ago gave those eloquent warnings about the evils of mass immigration, once said that if Britain were at war he would fight for Britain, even if it was a communist dictatorship.

The Greek poet in Byron’s Don Juan, living under the Ottoman Turks, likewise looked back to the Greek tyrants of antiquity and sighed:

I’m basically on the same page with these nationalists, but with reservations. When the Vietnamese army put an end to the Khmer Rouge government by invading Cambodia, most Cambodians hailed them as liberators. Perhaps I would have, too; perhaps even Enoch Powell would have.

So there are qualifications to be made about nationalism, especially small-country nationalism or sub-nationalism. You’re not drawing from a big pool of political talent there. I have mixed occasionally with Scottish and Welsh nationalists; let’s just say I wasn’t impressed.

Sub-nationalism like Catalonia’s is also in contradiction to nationalism proper. Who’s the truer nationalist: the Spanish citizen who would fight and die for Spain, or the Catalan separatist who feels the same way about his province?

You don’t have to recall horrors like Cambodia or North Korea to develop some caution about nationalism. Growing up in mid-20th-century England, we had an instance of passionate nationalism — or sub-nationalism, depending on your point of view — right on our doorstep. That was of course Ireland.

The Irish had been struggling for centuries to attain self-government. In 1921, aftersome revolutionary violence, they got autonomy; then in 1937, full independence.

Irish nationalism was a peculiar thing, though. The Irish had the nationalist impulse, all right: they wanted to be ruled by their own people, not by foreigners. Yet they also had strong trans-nationalist sentiments by virtue of being devout adherents of Roman Catholic Christianity — a trans-nationalist enterprise if ever there was one.

Having won their independence, the Irish signed on to every trans-national organization that came along. When I took my wife on a tour of the United Nations headquarters in 1987, our tour guide was an Irishman, and we heard a lot of Irish accents around the building.

Likewise with the European Union, on which the Irish are very keen. The sour joke in Britain thirty years ago was that having fought eight hundred years for their independence, the Irish had then sold it for a package of EU agricultural subsidies.

That’s not altogether fair. But looking at Ireland today gives you a jaded perspective on Irish nationalism. The seminaries are full of Nigerians [ How Catholicism fell from grace in Ireland, Chicago Tribune, July 92006] the cab drivers are all Polish; and the current Prime Minister, Leo Varadkar, is an open homosexual whose father was an Indian born in Bombay.

For this the heroes of 1916 faced the firing squads?

You may say that the right to national independence includes the right to national suicide. I suppose it does. Still, as a fan of Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s observationthat “Nations are the wealth of mankind, its collective personalities,” I lament the transformation of Ireland, the Land of Saints and Scholars, into an airport departure lounge — with the rest of Britain not far behind, indeed in some respects ahead.

“What was long divided must unite, what was long united must divide.” Hearing that now we Americans of course think of the secession talk that seems to be getting more and more common on the blogs, including very smart and sensible ones like the Audacious Epigone.

All right; history has its ebbs and flows, to be sure, and to stand athwart them crying “Stop!” is most likely futile. As a conservative, though, I rather strongly favor leaving the big old nations as they are, absent some obvious and pressing need to break them up.

So without knowing much about Catalonia or its independence movement, I’ll register myself as guardedly skeptical, on general grounds. America for Americans; Spain for Spaniards; nationalism over trans-nationalism and sub-nationalism both.

Last week I wrote about the coming centenary of the Bolshevik coup d’état in Russia. At the New York Times they’re already starting to hang out the bunting.

Last week I wrote about the coming centenary of the Bolshevik coup d’état in Russia. At the New York Times they’re already starting to hang out the bunting.

The tension between nationalism and imperialism was a factor in Lenin’s revolution. Tsarist Russia was an empire; it included numerous non-Russian nationalities. What plan did the Bolsheviks have for them?

Irish historian Frank Armstrong had a thoughtful op-ed on this in Wednesday’s Irish Times, contrasting the Bolshevik coup of 1917 with the Easter Rising in Ireland the previous year.[ Men of 1916 had much in common with Bolsheviks | But October Revolution and Easter Rising had radically diverging ideologies,October 5, 2017] . He points out the tension among Bolsheviks, notably Stalin, between, on the one hand, the orthodox Marxist line that “the proletariat has no homeland” and nationalism is a reactionary bourgeois impulse, and on the other hand, admiration for revolutionary violence like that practiced by the Irish rebels.

Armstrong doesn’t go anywhere much with his op-ed, but it’s a useful reminder that nationalists and trans-nationalists can find themselves thinking the same thoughts.

Here’s where I renew my call for a worldwide alliance of nationalists along the lines of the old Comintern, the Communist International.

We can call this alliance the Natintern, the Nationalist International. I’m still waiting for someone to come up with a suitable anthem, to be called of course The Nationale.

![2010-12-24dl[1]](https://www.vdare.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/2010-12-24dl1-150x112.jpg) John Derbyshire [email him] writes an incredible amount on all sorts of subjects for all kinds of outlets. (This no longer includes National Review, whose editors had some kind of tantrum and fired him. ) He is the author of We Are Doomed: Reclaiming Conservative Pessimism and several other books. He has had two books published by VDARE.com com:FROM THE DISSIDENT RIGHT (also available in Kindle) and FROM THE DISSIDENT RIGHT II: ESSAYS 2013.

John Derbyshire [email him] writes an incredible amount on all sorts of subjects for all kinds of outlets. (This no longer includes National Review, whose editors had some kind of tantrum and fired him. ) He is the author of We Are Doomed: Reclaiming Conservative Pessimism and several other books. He has had two books published by VDARE.com com:FROM THE DISSIDENT RIGHT (also available in Kindle) and FROM THE DISSIDENT RIGHT II: ESSAYS 2013.

(Republished from VDare.com by permission of author or representative)

http://www.unz.com/jderbyshire/if-catalonia-why-not-california-texas-or-new-england/

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home