In 1971, the U.S. Navy Almost Fought the Soviets Over Bangladesh

Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger had a terrible idea

by SEBASTIEN ROBLIN

In 2016, the United States backed India’s application to join the Nuclear Suppliers Group — but didn’t support Pakistan’s. This marked an extraordinary turning point in the United States’ relationship with these historical adversaries.

In 1971, the United States sent part of its Seventh Fleet to threaten war with India on Pakistan’s behalf.

The reasoning behind the deployment is stranger still — it was supposedly to befriend China.

The convoluted Cold War schemes of Pres. Richard Nixon and National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger help to explain why the United States threatened war with the second most populous country on Earth while also seeking to court the most populous country on the planet.

When the United Kingdom withdrew from colonial rule of the Indian subcontinent in 1947, the territory was partitioned into Hindu-majority India under the leadership of Jawaharlal Nehru and Muslim Pakistan under Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

However, there were large Muslim populations on both the western and eastern flanks of the Indian sub-continent — resulting in Western and Eastern Pakistan being separated by over a thousand miles, with India in the middle.

Western Pakistan contained the capital, where the Punjabi political elites of the new nation resided. East Pakistan was populated by the Bengali, an entirely different culture speaking an entirely different language.

A significant Hindu minority resided there, unlike in West Pakistan. Despite constituting the majority of Pakistan’s population, Bengalis were second-class citizens and received little development aid.

Pakistan and India almost immediately went to war over Kashmir, a Muslim-majority state whose Hindu ruler elected to join India in exchange for assistance putting down a local revolt. The incident escalated to a full-scale confrontation which simmers to this day.

During the 1950s, the United States and the Soviet Union vied to recruit India and Pakistan into their respective Cold War camps. India remained a democracy, and led the non-aligned movement seeking to avoid entanglement with one side or the other.

However, India’s cordial relationship with the Soviet Union, including major arms deals, resulted in uneven relations with Washington.

Pakistan, by contrast, received most of its military and economic aid from the United States. Military coups in Pakistan didn’t sour the relationship — but a 1965 war between India and Pakistan brought an embargo on all U.S. military aid to both countries. Millions in economic aid continued to flow, however.

The Chinese connection

By the late 1950s, a new factor came into play — Mao Zedong’s Communist China. Beijing had been a close ally of Moscow, but when the new Soviet premiere, Nikita Khrushchev, repudiated Stalin’s tyrannical policies, Mao took it as a personal affront.

The resulting so-called Sino-Soviet Split was the messiest of divorces. The Soviet Union may arguably have come closer to war with Chinathan it ever did with the West. The Soviet Union’s foreign policy and those of China would no longer coincide.

China borders both India and Pakistan through Tibet and the once predominantly Muslim province of Xinjiang. The Indian government had disputes with Mao over the precise boundaries of the McMahon line establishing the Himalayan border and had granted asylum to the Dalai Lama in 1959.

In 1962, the Chinese army overran Indian army outposts in the Himalayas in a one-month war. Beijing declared a ceasefire that deeply humiliated India.

The conflict compelled Pakistan and China to grow closer, and China began to provide Pakistan military equipment after the U.S. embargo came into force. China built roads to connect the two countries. Thus Pakistan was in the unique position of being cozy with both the United States and Communist China.

In the late 1960s, Kissinger developed a scheme to tip the Cold War in the West’s favor. The United States would entice China, already at odds with the Soviet Union, into an alliance!

But the United States still did not have any diplomatic relations with China — and needed to establish contact through a proxy that wouldn’t spill the beans to Moscow. Two options were under consideration — Pakistan and Romania. The Pakistani connection was more successful.

Gen. Yahya Khan, the president of Pakistan, agreed to pass on the messages to the Chinese embassy. In return, Nixon promised political support, as well as a one-time exception to the arms embargo in the form of 300 M-113 armored personal carriers and $50 million in replacement parts for Pakistani fighter jets.

Genocide in Bengal

The under-development and under-representation of East Pakistan by the West Pakistan-based government caused unrest and support for secession to grow among Bengalis.

Eventually, the majority gave its support to the Awami League led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, a charismatic politician who wanted to grant East Pakistan greater autonomy but did notadvocate secession. The movement was led by students and university faculty in part inspired by the 1960s protests in the West.

When the deadliest cyclone in history struck East Pakistan in November 1970, killing between and 300,000 and 500,000, West Pakistan provided minimal aid. In the 1970 parliamentary elections the following month, the Awami League won the majority of seats, which should have made Rahman prime minister of Pakistan.

But Khan delayed assembling the parliament and instead conspired with the second-place finisher, Socialist Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. Realizing the Awami League’s victory was being denied, Bengalis protested throughout East Pakistan.

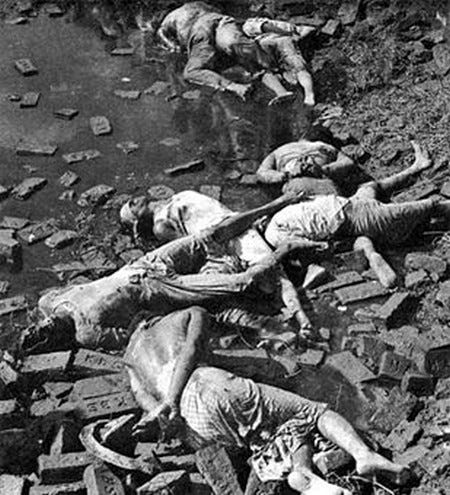

On March 15, 1971, Khan flew to East Pakistan and began negotiating with Rahman in the eastern capital Dhaka, while additional army units began arriving from West Pakistan by air and sea. On March 25, Rahman thought he had arrived at a deal with Khan. Instead, Khan slipped away by plane back to West Pakistan, and at midnight, the Pakistani army sprang into action in Operation Searchlight, arresting Rahman and many leaders of the Awami League.

Pakistani soldiers, aided by Islamist paramilitary militias, opened fire on protesters and executed political dissidents and Hindus. More than 1,100 intellectuals were rounded up, tortured and executed. Tens — possibly hundreds — of thousands of Hindu and Bengali women were raped by soldiers and paramilitaries, encouraged by fatwas issued by imams stating that Hindu and Bengali women could be claimed as gonimoter maal — “war booty.”

Several East Pakistani army units mutinied and returned fire. By the end of April, millions of Hindus, accompanied by Bengali political activists and rebellious East Pakistani military units, poured over the border into massive Indian refugee camps.

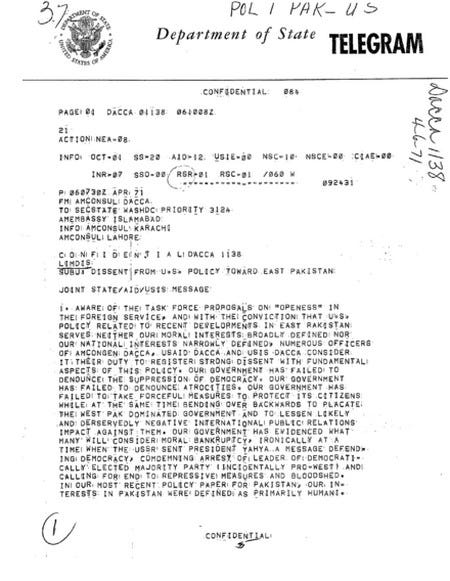

Archer Blood, the State Department’s consul general in Bengal, sent a cable to Washington on March 27. “Here in Decca we are mute and horrified witnesses to a reign of terror by the Pak[istani] military,” Blood wrote. “Evidence continues to mount that the MLA authorities have list of AWAMI League supporters whom they are systematically eliminating by seeking them out in their homes and shooting them down.

“Among those marked for extinction in addition to the A.L. hierarchy are student leaders and university faculty. …

“Moreover, with the support of the Pak[istani] military, non-Bengali Muslims are systematically attacking poor people’s quarters and murdering Bengalis and Hindus.”

He and 20 diplomats later sent a famous protest telegram in which he called what was occurring “genocide.” Kissinger responded to Blood’s complaints by dismissing him from his post. “The use of power against seeming odds pays off,” Kissinger observed regarding the crackdown.

The death toll is commonly estimated between at 200,000 and 3 million. Kissinger’s tacit support for the massacres in Bangladesh is one of many incidents contributing to his poor record on human rights.

War for Bangladesh

The 10 million refugees gravely strained India’s national resources — and the Indian public was naturally sympathetic to the plight of Hindus chased from their homes by the Pakistani military.

At first reluctant to get involved, Indira Gandhi’s government eventually began to provide support to the exiled political leadership of the Awami League, and armed rebels called the Mukti Bahini. As it began to receive training and equipment from India, the Mukti Bahini launched raids deep into Bangladesh, igniting a full-scale insurgency. By November 1971, Indian infantry, artillery and even light tanks were actively engaged in raids on Pakistani border outposts.

The cause of the Bengals also acquired political support in the West and the Soviet Union. The British Sunday Times ran a story by Pakistani journalist Anthony Mascarenhas entitled “Genocide” that described the Pakistani operation.

On Aug. 1, 1971, former Beatle George Harrison and master sitar-player Ravi Shankar performed the first large-scale benefits concert in history, the Concert for Bangladesh in New York City, featuring Ringo Starr, Bob Dylan and Eric Clapton, among others.

Eight days later, India signed the Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation with the Soviet Union. The Indian government felt out other world powers for their reaction to an Indian intervention in the conflict and received the green light everywhere but in the United States.

Nixon was personally fond of Yahya Khan, and seems to have hated Indians, whom he called “slippery, treacherous people.” Of Indira Gandhi, he was recorded as saying, “The old bitch. I don’t know why the Hell anybody would reproduce in that damn country, but they do.”

The State Department wasn’t of the same opinion. India had many times the population of Pakistan and was more politically stable. But Kissinger overruled its objections — in his view, Pakistan was the key to wooing China.

In July 1971, Kissinger had already secretly flown from Pakistan to Beijing for the first diplomatic meeting between the United States and Communist China. “Yahya hasn’t had such fun since the last Hindu massacre!” Kissinger remarked.

Pakistan was in a poor position to withstand an Indian attack. On the outbreak of hostilities, it would be impossible to send reinforcements around India to the embattled Pakistani forces in East Pakistan. Khan tried to call on China and the United States to guarantee its support in the event of an Indian attack.

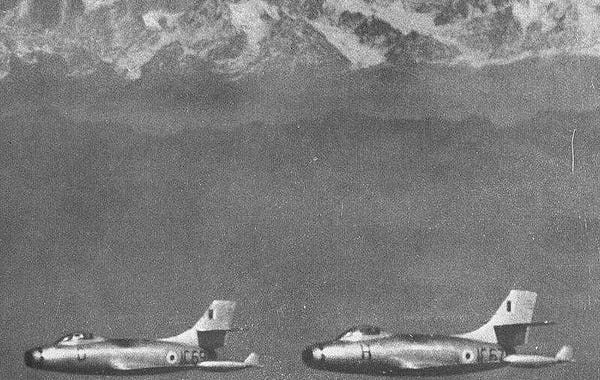

The Pakistanis launched the first open blow of the war on Dec. 3, with a preemptive strike on Indian airfields. But India had planned for war in advance. Its aircraft were safe inside concrete bunkers. While air, armor and artillery battles erupted along the border of West Pakistan and India, on the eastern border, nine Indian infantry divisions supported by an armored brigade of Soviet-made PT-76 and T-55 tanks plunged into Bangladesh. Fighting alongside them were 29 battalions of Mukti Bahini guerillas.

Opposing them were three regular and two ad hoc Pakistani infantry divisions supported by a single squadron of outdated M-24 Chaffee light tanks. The Indian forces made a blitzkrieg-style advance using Mi-4 helicopters to transport infantry cross Bangladesh’s large rivers, bypassing Pakistani strongpoints and cutting Pakistani units off from their supply lines. The Pakistani ground forces at first offered stiff resistance, but then began to collapse.

In the air, Pakistan had only one squadron of 20 F-86 Sabre fighters to defend against Indian’s 10 jet-fighter and two bomber squadrons, including three squadrons of deadly Soviet-made MiG-21s. Five Sabres and three Indian fighters were lost in aerial combat before Indian MiG-21s cratered the Pakistani runways on Dec. 5 and claimed air supremacy.

Task Force 74 sets sail

As total defeat loomed, Khan demanded that the United States come to his aid. Even though Kissinger didn’t need Pakistan to maintain his channels with China anymore, he persuaded Nixon that he should rattle sabers on behalf of Pakistan in order to preserve credibility with the Chinese.

Nixon asked China to mobilize its troops on the Indian border — and even contemplated “lobbing nuclear weapons” at the Soviet Union if the Soviets retaliated by going to war with China! But Chinese leaders, still enduring the instability of the Cultural Revolution, were uninterested in another war with India, and considered East Pakistan to be as good as lost.

Trying to circumvent the arms embargo, Nixon also tried to persuade other Muslim countries that if they sent arms to Pakistan, the United States would compensate them for the cost.

On Dec. 8, 1971, the U.S. Seventh Fleet received orders to dispatch Task Force 74 to the Bay of Bengal. The battle group was centered around the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise, accompanied by nine other ships including a nuclear attack submarine. The move occurred in the face of opposition from the naval leadership, including Adm. Elmo Zumwalt, who knew it could achieve little.

Enterprise departed from the Gulf of Tonkin — where it was deployed for the Vietnam War — on Dec. 10 and set sail for the Bay of Bengal, arriving on Dec. 15.

For the Indians, the implied threat was clear — the Seventh Fleet might send its 90 fighters and bombers in support of the Pakistani army. India instructed its forces in East Pakistan to hasten the capture of key cities, while those in the West were told to refrain from advancing too far so as not to give a pretext for U.S. intervention.

Would the United States have actually attacked? It seems unlikely. While the U.S. aircraft might have seized air superiority over Bangladesh, they could not have reversed the outcome of a military campaign the Pakistani army was losing crushingly on the ground. The United States was also still involved in the Vietnam War, and starting a new conflict with India would have been a domestic and international disaster.

In fact, some argue that Task Force 74 was actually intended to pressure theSoviets to make India call off the war. According to this explanation, the task force would harass Soviet ships in the Bay of Bengal, not attack India — a plan which Navy leadership thwarted by slowing the Enterprise’s cruise with a fueling stop in Singapore and assigning it to a corner of the Bay of Bengal where there was a low probability of encountering Soviet ships. They were worried an accident could provoke World War III.

Indeed, a Soviet naval task force from Vladivostok consisting of a cruiser, a destroyer and two attack submarines under the command of Adm. Vladimir Kruglyakov intercepted Task Force 74 in the makings of a deadly Cold War standoff. Kruglyakov gave a rousing account in a T.V. interview of “encircling” the task force, surfacing his submarines in front of the Enterprise, opening the missile tubes and “blocking” the American ships.

But U.S. records don’t recount an encounter with the missile-laden Soviet vessels until Dec. 19, three days after events had already been decided on the ground.

The bitter end

Task Force 74 was too late. The real arbiter of Pakistan’s fate would be the United Nations. Political pressure was mounting for India to agree to ceasefire with Pakistan as the latter’s forces crumbled on all fronts.

A U.N. resolution tabled by Poland might have ended the conflict without handing India a clear victory — the Eastern capital of Dhaka was still not under Indian control. Yahya Khan instructed Ali Bhutto, at the United Nations in New York, to accept.

Instead, on Dec. 15 Bhutto gave a fiery speech decrying it. “I will not be party to the ignominious surrender of part of my country. You can take your Security Council. Here you are. I am going.”

With that he walked out, tearing the resolution papers apart — along with the Pakistani army’s last chance to extricate itself intact.

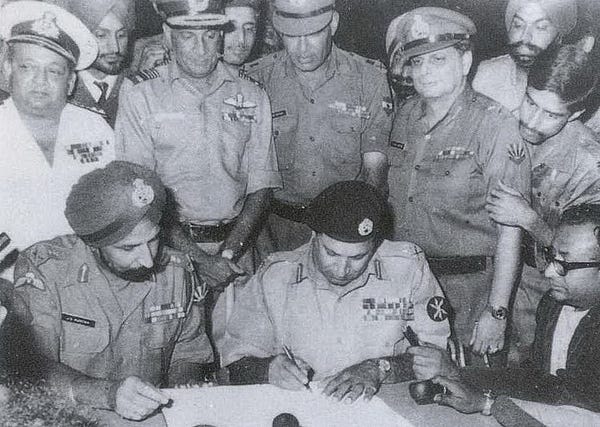

The next day Pakistan’s forces in East Pakistan — all 93,000 Pakistani troops and civil servants — unconditionally surrendered and entered Indian custody. Two days later, Yahya Khan stepped down and Bhutto assumed the presidency.

East Pakistan was gone — and the new nation of Bangladesh was born.

Aftermath

Nixon’s famous trip to China in 1972 would prove one of the diplomatic coups of the century. Although predating the “Reform and Opening” policy instituted by Deng Xiaoping in 1978, the opening of ties with the United States undoubtedly played an important role in China’s rise as a world power.

Nixon and Kissinger would claim that Task Force 74 helped save West Pakistan from invasion, though India never had any plans to invade it in the first place. In fact, though the United States and Russia both tried to claim their navies had an impact, the 1971 war was completely decided by the local actors — Indians, Bengalis and Pakistanis.

India would not forget the incident with the Seventh Fleet, hastening its development of nuclear weapons, achieved in 1974. Relations with the United States warmed during the 1980s, but not until the late 1990s and early 2000s did the United States succeed in getting back on good terms with India, particularly following U.S. mediation of the Kargil War with Pakistan in 1999 and a civilian nuclear technology agreement in 2005.

Bangladesh, one of the most densely-populated countries in the world, would suffer several violent military coups, the first of which killed Sheikh Mujibir Rahman. Today it is a secular, multi-party democracy, though it’s plagued by corruption and a recent spate of murders committed by Islamic fundamentalists.

Rahman’s daughter, Sheikh Hasina Wazed is currently prime minister. Her government has executed several opposition leaders on charges of war crimes committed during the genocide.

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto would rule Pakistan for six years before being overthrown and later executed, replaced by an Islamic fundamentalist military dictatorship under Gen. Zia Al Haq.

India’s border with Pakistan and China remains among the most heavily-militarized in the world.

https://warisboring.com/in-1971-the-u-s-navy-almost-fought-the-soviets-over-bangladesh-c65489bc72c0#.48sybglfi

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home