How ‘bling’ makes us human

Decorating our bodies: expanding our minds

For archaeologists, finding body adornments is the closest thing to finding prehistoric thought. Their first appearance in the archaeological record tells us when the human mind had become sophisticated enough to conceive of individual identities.

Originally, humanity lived in small groups that were spread out across the landscape. Everyone knew everyone, and interactions between complete strangers were a rare occurrence.

Growing populations, however, led to an increasingly complex social world in which we didn’t know every individual personally. This meant we needed to start telling people who we were.

So, we began wearing certain things to send messages regarding our personal status (available, married, leader, healer) and group affiliations.

This use of body decorations enabled humans to continue expanding our communities, which lead to more complex behaviours and more complex minds.

Origins in body paint

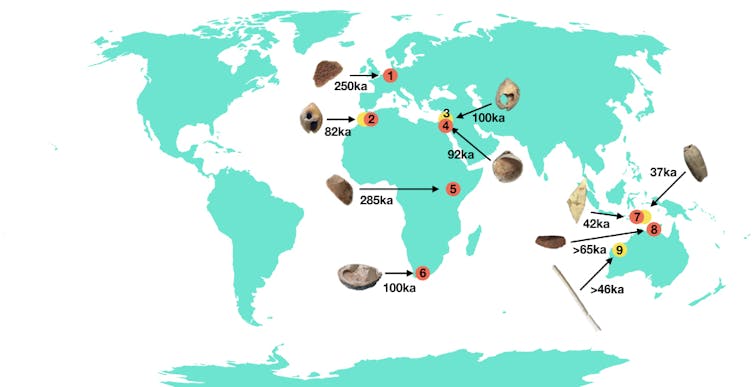

The earliest evidence for bling is red pigments – mineral earth ochres – which were used as body paints by modern humans (Homo sapiens like orselves) some 285,000 years ago in Africa.

Interestingly, it appears that not long after (around 250,000 years ago), Neanderthals were doing the same thing in Europe.

However, body paint only lasts for so long – until you wash, it rains, or it simply wears off. It has a time limit.

Beads, beads, and more beads

Beads, on the other hand, can last for generations. This ability to be used and reused significantly outweighs the time and energy it takes to make them – and by at least 100,000 years ago, people both needed and recognised the advantages of beads.

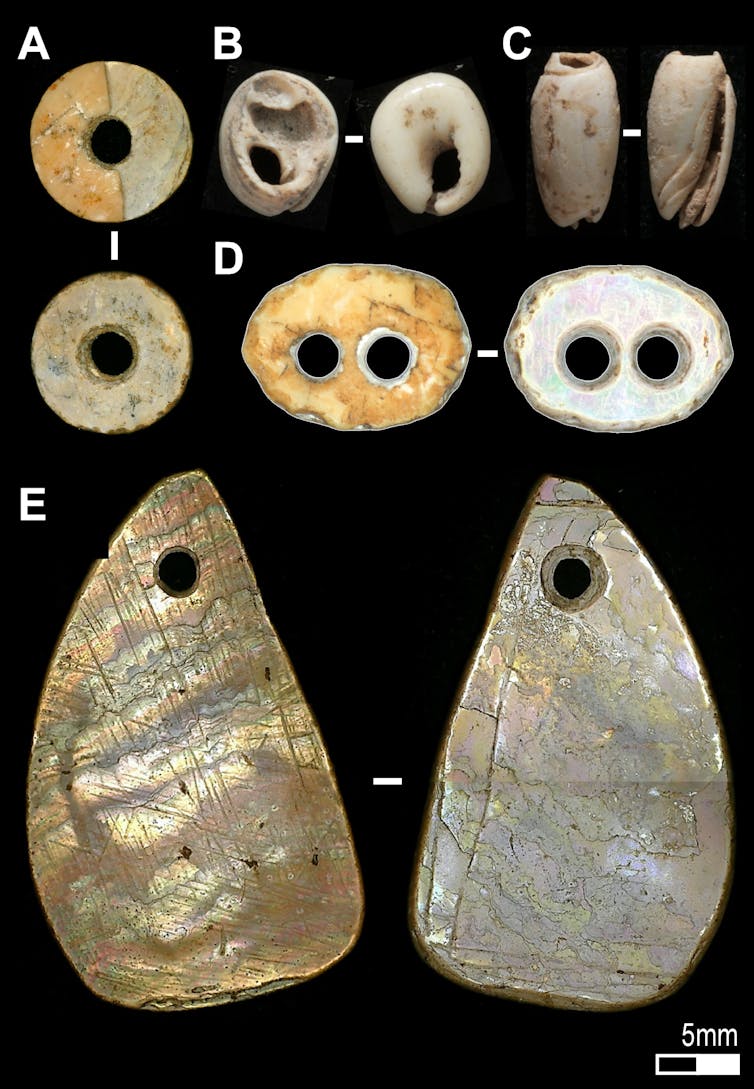

Around this time, people in Africa and in Israel were seeking out tiny white shells called Nassarius, punching a hole through their surface so they could be strung, and using them alongside red body paint.

It is not an accident that the oldest beads are made from seashells: they come in shapes we like (round), colours we like (white/cream/black), and are shiny (we like this a lot). Small shells are also hardy, being able to withstand being jolted or dropped (useful).

What’s more, they can be worn in a wide variety of ways – allowing us to transmit many different messages.

Soon we found other light coloured and shiny materials (bone, tooth, ivory, antler, stone) to make new types of ornaments and send even more messages.

Getting inked

What’s more permanent than beads? Inserting ink into the dermis layer of the skin – also known as tattooing.

Sculptures from Europe suggest that tattooing may have an antiquity of at least 30,000 years, though the earliest indisputable evidence for tattooing is currently the Tyrolean iceman commonly known as “Ötzi”.

The victim of murder some 5,300 years ago, Ötzi sports some 61 skin markings. Similarly aged are two predynastic Egyptian mummies, while a younger, spectacular example is a 2,500-year-old Siberian princess.

Tattooing also has an impressive history throughout the Pacific, inspiring modern practices while simultaneously passing on ancient stories.

Bling is human

Because bling is so closely tied to communication, archaeologists are able to track not only the development of our minds, but also the development of our societies.

For us, more bling in the archaeological record indicates more interactions. Traded bling tells us who was talking to whom. And new types of bling reflect changed circumstances.

All bling is valuable because it tells us something about the person who wore it.

This article is based on a series of lectures Michelle delivered at the Abbey Museum of Art and Archaeology and the Queensland College of Art - Griffith University in July and August 2018.

https://theconversation.com/how-bling-makes-us-human-101094

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home